|

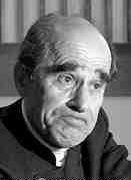

Former Waffen-SS officer cadet, and more recently retired Concordia University economics professor, Hungarian-born 75-year-old Adalbert Lallier, was induced by Steven Rambam to finally break his vow of silence that he had sworn to his Nazi comrades by stating in 1997 that he had seen Julius Viel murder seven Jews in 1945. |

|

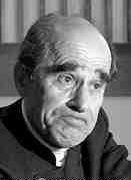

Former Waffen-SS Untersturmführer (2nd lieutenant), and more recently retired newspaper editor, 83-year-old Julius Viel, convicted in Revansburg in 2001 for murdering seven Jews in 1945, and sentenced to 12 years imprisonment. |

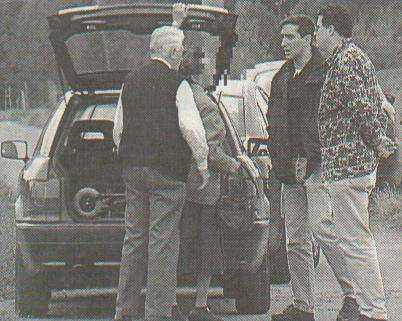

| From left to right, Mr. and Mrs. Julius Viel confronted by Steven Rambam and reporter Eric Friedler. This publicity stunt attempted to discompose Julius Viel, to provide him with the opportunity to blurt out something ill-advised that could be quoted to his discredit, and to provide a photo opportunity to bolster Rambam's credentials as a Nazi hunter. As Mrs. Viel is not a party to the proceedings, the photograph masks her features. |

homepages.compuserve.de/jththanner1/eingeholt.htm |

| 25 March 2002 |

|

Officials close to the case, however, fear that accused Nazi war criminal Julius Viel may never face justice unless additional witnesses in the case come forward during the next few months. That was also the appraisal of private investigator Steven Rambam, the Nazi hunter who was responsible for 'turning' a former SS inductee, "L", and bringing him to testify before a German judge. L's testimony lead directly to Viel's arrest last month for the murder of seven Jewish inmates at the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia.

Jerusalem Post, 29-Nov-1999, at www.pimall.com/nais/nl/n.rambam.html |

|

The case would never have come to court — let alone to a guilty verdict — had it not been for the testimony of Mr. Lallier, a native Hungarian who immigrated to Canada in the 1950s.

Karl-Anton Maucher, Ottawa Citizen, 04-Apr-2001, Final Edition, p. A1. |

|

With only one eye-witness, Lallier's credibility is the central question facing the panel of five judges.

Karl-anton Maucher And Kate Jaimet, The Gazette (Montreal), 05-Mar-2001, Final Edition, p. A8. |

|

"If you are a war criminal, this is your last chance because if you don't come forward and co-operate with us, we may very well end up building a case against you with another co-operative witness. The train is leaving the station, come forward, do the right thing and we'll try to help you."

Steven Rambam quoted by Stephen Bindman, Gazette (Montreal), 20-Mar-1997, Final Edition, p. E10. |

|

Rambam did not distinguish between degrees of wrongdoing when he said the congress would interview and re-interview suspects against whom war crimes allegations had been made to see if they are willing to give evidence against their "co-conspirators in murder. "We are telling these people that we want them to come forward and give evidence against the people with whom they murdered civilians," he said. "If they do so we will go on their behalf to the RCMP and to the justice minister to try to strike a deal for them." David Vienneau, Toronto Star, 23-Mar-1997, p. 86. |

|

According to Farber of the Canadian Jewish Congress, the man himself must also be considered a war criminal. "He confined innocent people, seven of whom were eventually murdered. In my books, that's an accessory to murder. That's a war crime."

Ellie Tesher, Toronto Star, 10-Jun-1997, Metro Edition, starts on p. 84. |

|

Several other witnesses testified they recall hearing rumours in spring of 1945 that Viel had been involved in a shooting of one or more prisoners. But Pfliegner says Lallier might have heard the same rumours. "Maybe Lallier had this somewhere in his memory. ... He said: 'Viel had something to do with some shootings, so I won't be fingering a totally innocent man.' " Karl-anton Maucher And Kate Jaimet, The Gazette (Montreal), 05-Mar-2001, Final Edition, p. A8. |

|

"He says his conscience is tormenting him after 55 years," Mr. Pfliegner says. "I don't believe it." Mr. Pfliegner contends Mr. Lallier fingered Mr. Viel in order to stave off investigation into his own membership in the Waffen-SS. The year Mr. Lallier made his accusation, the Canadian Jewish Congress was lobbying the Justice Department to become more aggressive in pursuing the files of suspected Nazi war criminals living in Canada. The Congress even set up a "snitch line" in Montreal, manned by Mr. Rambam. Mr. Pfliegner contends that Mr. Lallier was afraid that someone would come forward and denounce him as a former SS-man. Rather than waiting to be targeted, he took the pre-emptive move of voluntarily confessing his membership in the Waffen-SS, and simultaneously denouncing Mr. Viel, the defence lawyer argues. Karl-Anton Maucher and Kate Jaimet, Ottawa Citizen, 04-Mar-2001, Final Edition, p. A5. |

|

There were about 1,500 inmates digging that day, Rambam said.

Janice Arnold, Canadian Jewish News, Internet Edition, at www.cjnews.com/pastissues/00/jan13-00/front1.htm |

|

He relates that in the last days of the war, with enemy forces approaching from the east and west, over 1,700 inmates from the concentration camp were forced to dig antitank ditches.

Irish Times, City Edition, 05-Dec-2000, p. 12 |

|

"My detachment was sent, with Viel heading the detachment, to receive about 2,000 Jewish camp inmates — half-starved, as it turned out — march them to the plains and watch over them as they dug an anti-tank ditch," Mr. Lallier recalls.

Kate Jaimet, Ottawa Citizen, 13-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p. A3 |

|

The Nazis oversaw a forced march of "at least 4,000 to 5,000" Jewish inmates whom he describes as "coming out in long columns in their striped prisoner uniforms" from the camp to an area where they were required to build a massive ditch to a depth impossible to climb. They were guarded by "thousands of German troops," the man says.

Ellie Tesher, Toronto Star, 10-Jun-1997, Metro Edition, p. A2. |

|

The officer shot one of the men four times and only stopped firing when his carbine was empty.

Ellie Tesher, Toronto Star, 10-Jun-1997, Metro Edition, p. 84 |

|

Mr. Lallier recalled how one victim, a giant of a man with a dark beard, defied his killer. "I'll never forget it in my life," he said. "He raised his hand and turned full-face to where the shot was coming from and cursed the man. In no time, he had three more shots and he fell over, too."

Joanne Laucius, Ottawa Citizen, 05-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p.A1 |

|

"He starts shooting. A first man, a second, then a big one with a red beard. The shot hits him. He falls, raises himself up, looks to see where it came from, raises his arm. The second shot hits him. Then many more, the weapon was shot until it was empty."

Canadian Press Newswire, 14-Dec-2000, Section D |

Gordon Williamson, The SS: Hitler's Instrument of Terror, Motorbooks International, Osceola WI, 1994, pp. 204-205. |

|

Lallier says he was tormented by his memories, yet bound by an oath of silence and loyalty to his ex-comrades. Finally, in 1997, his conscience would no longer allow him to keep the secret hidden and he denounced Viel to an American Nazi-hunter named Steve Rambam.

Karl-anton Maucher And Kate Jaimet, The Gazette (Montreal), 05-Mar-2001, Final Edition, p. A8 |

|

After the shooting, Mr. Lallier said, the commandant of Waffen SS officers' school, Lt.-Col. Willi Kruft, ordered the witnesses to swear an oath never to tell anyone.

Kate Jaimet, Ottawa Citizen, 13-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p. A3. |

|

Mr. Lallier, who was born in Hungary of French Huguenot descent, was only 17 and barely out of high school when he and his brother Andreas were taken against their will into the signal corps of the Waffen SS, the fighting arm of the SS, Hitler's elite guard.

Joanne Laucius, Ottawa Citizen, 05-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p.A1 |

|

"We then heard that a German draft list had been created. Suddenly, a German colonel showed up at our home, looked at me and my brother-Andre was 20 and I was 17 — and warned us not to try to run away or we would be caught and shot."

Bram Eisenthal, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 10-Apr-2001, at www.zipple.com/newsandpolitics/internationalnews/20010410_ss_speaks.html |

|

He told the students he was about their age when he was forced to join the SS in his native Hungary, under threat of being shot.

Janice Arnold, Canadian Jewish News, Internet edition, 31-May-2001, at www.cjnews.com/pastissues/01/may31-01/front3.asp |

|

"To kill seven Jews, in the ditch, half-starved, without any means of self-defence, you know that it's wrong. The military code tells you that officers will never consent to shooting an unarmed enemy."

Kate Jaimet, Ottawa Citizen, 13-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p. A3. |

|

"I decided that on behalf of humanity my highest allegiance is to the process of natural justice, not to Hitler."

Janice Arnold, Canadian Jewish News, Internet Edition, 31-May-2001 at www.cjnews.com/pastissues/01/may31-01/front3.asp |

|

The Germans sought to avoid damage to "the soul" [...] in the prohibition of unauthorized killings. A sharp line was drawn between killings pursuant to order and killings induced by desire. In the former case a man was thought to have overcome the "weakness" of "Christian morality"; in the latter case he was overcome by his own baseness. That was why in the occupied USSR both the army and the civil administration sought to restrain their personnel from joining the shooting parties at the killing sites. [In the case of the SS,] if selfish, sadistic, or sexual motives [for an unauthorized killing] were found, punishment was to be imposed for murder or for manslaughter, in accordance with the facts.

Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, 1985, pp. 1009-1010. |

|

The killing of the Jews was regarded as historical necessity. The soldier had to "understand" this. If for any reason he was instructed to help the SS and Police in their task, he was expected to obey orders. However, if he killed a Jew spontaneously, voluntarily, or without instruction, merely because he wanted to kill, then he committed an abnormal act, worthy perhaps of an "Eastern European" (such as a Romanian) but dangerous to the discipline and prestige of the German army. Herein lay the crucial difference between the man who "overcame" himself to kill and one who wantonly committed atrocities. The former was regarded as a good soldier and a true Nazi; the latter was a person without self-control, who would be a danger to his community after his return home.

Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, 1985, p. 326. |

|

Every unauthorized shooting of local inhabitants, including Jews, by individual soldiers [...] is disobedience and therefore to be punished by disciplinary means, or — if necessary — by court martial.

Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, 1985, p. 327. |

|

Lviv, 8/21/42. Head of the Commissariat Michael Hanusiak, Lest We Forget, New York, first printing 1973, second printing 1975, p. 139. Printed by Commercial Printers, Dunnellen, N.J. |

|

Q. Now, how extensive did these investigations become? [...] A. I investigated Weimar-Buchenwald, Lublin, Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, Oranienburg, Herzogenbosch, Cracow, Plaschow, Warsaw, and the concentration camp at Dachau. And others were investigated after my time. Q. How many cases did you investigate: How many sentences were passed? How many death sentences? A. I investigated about 800 cases, or rather, about 800 documents, and one document would affect several cases. About 200 were tried during my activity. Five concentration camp commandants were arrested by me personally. Two were shot after being tried. Q. You caused them to be shot? A. Yes. Apart from the commandants, there were numerous other death sentences against Führers and Unterführers. The trial of German major war criminals: Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg Germany, His Majesty's Stationery Office, Part 20, 07-Aug-1946, p. 381. |

|

Suddenly, without warning or provocation, Mr. Lallier saw Mr. Viel pick up a carbine, take aim, and shoot seven prisoners dead in the ditch.

Karl-Anton Maucher, Ottawa Citizen, 04-Apr-2001, Final Edition, p. A1 |

|

Lallier said that he saw nothing that could have provoked the attack, and that the officer was not berserk. No one apprehended him, and he apparently suffered no consequences, even though higher ranking officers were present.

Janice Arnold, Canadian Jewish News, 13-Jan-2000, at www.cjnews.com/pastissues/00/jan13-00/front1.htm |

|

No action was taken against Viel at the time, although the incident may have been witnessed by hundreds.

Canadian Jewish News, 03-Aug-2000 at www.pallorium.com/ARTICLES/art19.html |

|

The Red Army is rolling over the German Army, heading straight for Berlin, and obviously about to subject the German people to a humiliating defeat and to unimaginable suffering. Understandably, Julius Viel is frustrated, bitter, and angry. He struggles valiantly to make his small contribution to staving off defeat, but realizes all the while that it will never be enough. Certainly this pathetic tank ditch — so hard for the Germans to build, and yet so easy for the Soviets to bridge or to circumvent — will make little difference. If only Germany could muster support, could energize those laboring on its behalf — willingly or unwillingly — then there might still be some chance, there might still be enough delay that Hitler could produce the magic super-weapon that he was working on and that the German army was waiting to turn upon the enemy. But what was Viel getting from these workers? Why nothing but insubordination and foot-dragging! These workers acted as if Germany had already lost the war, and as if there were no point busting their asses to help Germany reverse that loss. This tank-ditch project was dragging on, and these workers were making a joke of it, scratching away with their tools as if they were children in a sand box, whining for rests for claimed exhaustion. Exhaustion! — How could they be exhausted when they didn't work? They appeared well enough rested to Julius Viel, not to mention well enough fed. In fact, in comparison to his own German boys who had been on short rations for months now, some of these workers appeared positively plump. And in any case, the fate of Germany, Europe's leading civilization, was at stake, so was it too much to ask these prisoners to work through their fatigue and to cut back on their caloric intake? And here this particular group of workers seemed to form some sort of nucleus of resistance. They started the day by feigning illness. Then came an interval of horsing around. And now they were lolling about. They seemed content to accomplish exactly nothing. They responded to requests to redouble their efforts with insolence. They were practically sabotaging the project. And there they were now leaning on their shovels, one having a smoke, holding his cigarette daintily like a gentleman, and behind him another was eating chocolate! Cigarettes? Chocolate? Where did these beggars get cigarettes and chocolate? Who did they think they were, enjoying luxuries that the German fighting men lacked? Was this a construction project, or a gentleman's club? The German army was sacrificing itself to save Europe from the Asiatic hordes on its doorstop, and these insolent beggars were standing around laughing, laughing as if it did not matter whether Germany lived or died, laughing while they smoked their cigarettes and nibbled their chocolates! They needed to be taught a lesson, these beggars. An example needed to be set for all the workers in this project — that sabotage will be punished, that those who refuse to join the defense of Europe against the Slavic barbarians must pay a price. The last straw was when Viel locked eyes with one of the workers, the insolent ringleader of this nucleus of saboteurs, and that ringleader stared back at him unafraid. Viel's gaze did prove the stronger, but as the ringleader turned away, he spat. That is when Julius Viel lost control. He shouted to the nearby guards to encircle these saboteurs, these Bolsheviks wallowing in their stinking ditch, these smokers and chocolate-eaters, and he ordered the guards to open fire. The guards did encircle the trench as they were ordered, and they did raise their rifles, but their fingers froze on the triggers. They were young men who had not seen action, were unused to killing, and below them in the ditch stood not incarnations of evil, not Bolsheviks frustrating German defense efforts, but only men like themselves, trapped by fate on the other side of a conflict initiated by others, and all — irrespective of side — united by their common prayer that the war end. These young guards had been brought here to guard, not to kill, and could not readily jump rails from the easy role to the difficult one. Seeing that action depended on himself alone, and used to taking the lead and setting an example, Viel shouted "If anybody tries to escape, shoot him!", pulled out his pistol, and began walking around the rim of the pit firing at the workers inside. Some of the workers tried to scramble out of the ditch, and these particularly drew the fire of Viel, and guards who had found themselves unable to shoot workers standing still in a ditch, suddenly did find themselves able to shoot once they heard others shooting, and once the victims were transformed in their perception from workers into escaping prisoners. After it was over, it was not readily apparent exactly who had killed who. There had been some shooting on the part of the guards, undeniably, but nobody had any idea of exactly how much, or with what effect. The young guards noted that the number of victims was seven, and the number of Viel's shots was eight — as Viel had eight rounds of ammunition in that pistol of his which he emptied, and which was either a Pistole 08 (or P08, known throughout the world as the Luger) or a Walther P38, either of which carried eight rounds. The young guards whispered among themselves that eight shots was enough to kill seven workers. If the shooting of the young guards themselves contributed to the killing, that contribution was small and unimportant, and many began to recollect that they had shot only to appease Viel, but had aimed so as to miss. All eventually agreed that the full responsibility for all seven deaths fell upon Viel's eight bullets. Viel's immediate superiors did not act against Viel because they sided with him. They agreed that the project was dragging, and that the resistance of the workers was to blame. They agreed that fear was the missing ingredient needed to spur the workers to greater effort. They did not view Viel's action either as deranged or as inexplicable — they viewed it as resourceful labor management, severe but only because the times called for severity. They decided to hush the incident up. That is why Viel was never prosecuted, and that is why he was not institutionalized, and that is why he was not feared as a lunatic who posed a danger to his comrades. |

|

At the SS officers' school the next day, a memo was posted by their superior, he said. "It said, to the effect, what happened, happened; it can't be undone," he recalled three years ago. "If we win the war, we will not be responsible. If we lose, we will all be dead anyway." Ottawa Citizen, 05-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p. A1. |

|

German witnesses for the defense were excluded from the outset, since they would have exposed themselves to arrest and prosecution in Israel under the same law as that under which Eichmann was tried. (p. 114)

The documentary evidence was supplemented by testimony taken abroad, in German, Austrian, and Italian courts, from sixteen witnesses who could not come to Jerusalem, because the Attorney General had announced that he "intended to put them on trial for crimes against the Jewish people." (p. 200) It quickly turned out that Israel was the only country in the world where defense witnesses could not be heard [...]. (p. 201) Justice was more seriously impaired in Jerusalem than it was at Nuremberg, because the court did not admit witnesses for the defense. In terms of the traditional requirements for fair and due process of law, this was the most serious flaw in the Jerusalem proceedings. (p. 251) Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil, Viking Press, New York, 1963. |

|

Gill and Chumak went to Germany, to Hamburg. On 9-10 December they were to question a German SS man called Rudolf Reiss, who had been a sergeant at Travniki. I strongly objected to using his testimony [...]. [...] I was not prepared under any circumstances to use the testimony of Nazi thugs.

Yoram Sheftel, The Demjanjuk affair: The rise and fall of a show-trial, Victor Gollancz, London, 1994, p. 177. |

|

Gill, Nishnic and many people close to the Demjanjuk family, especially the anti-Semite Jerry Berntar, had incessantly pressed for the defence to take evidence from the Deputy Commandant of Treblinka, the fiend Kurt Franz. He had been sentenced to life imprisonment in 1964 in Germany, and was incarcerated until July 1993. I opposed this categorically, because using the testimony of Treblinka's Deputy Commandant would look very bad and could be interpreted as meaning that Demjanjuk had asked for his ex-commander's assistance. I emphasized also that in any case no court would believe Franz's claim that Ivan Demjanjuk was not Ivan the Terrible, since he had lied flagrantly at his own trial and denied all the atrocities he committed at Treblinka. Then there was my moral opposition, and at one point I even threatened to resign from the case. Our compromise was the Kurt Franz would not be called to testify for the defence; the defence would question Reiss, but I would not take part, nor would I refer to it in my summation.

Yoram Sheftel, The Demjanjuk affair: The rise and fall of a show-trial, Victor Gollancz, London, 1994, p. 177. |

|

Lt.-Col. Kruft died in 1993 without ever breaking his silence.

Kate Jaimet, Ottawa Citizen, 13-Dec-2000, Final Edition, p. A3. |