The Wheel Cipher

by Peter Rabbit

April 13, 1993 marked the 250th anniversary of the birth of Thomas Jefferson, who is known to all of us as the Father of the Declaration of Independence, and who should also be rightly known as the Father of American Cryptography.

Jefferson's major contribution to cryptography was his invention of the Wheel Cipher. This device consisted of up to 36 wooden wheels, resembling checker pieces, each with a hole in its center and a jumbled alphabet stamped around its periphery.

The wheels were secured onto an iron rod, the common axis on which they turned. The Wheel Cipher worked as a moveable mixed-alphabet table of 26 columns and a maximum of 36 rows; that is, each wheel was one row on the alphabet table.

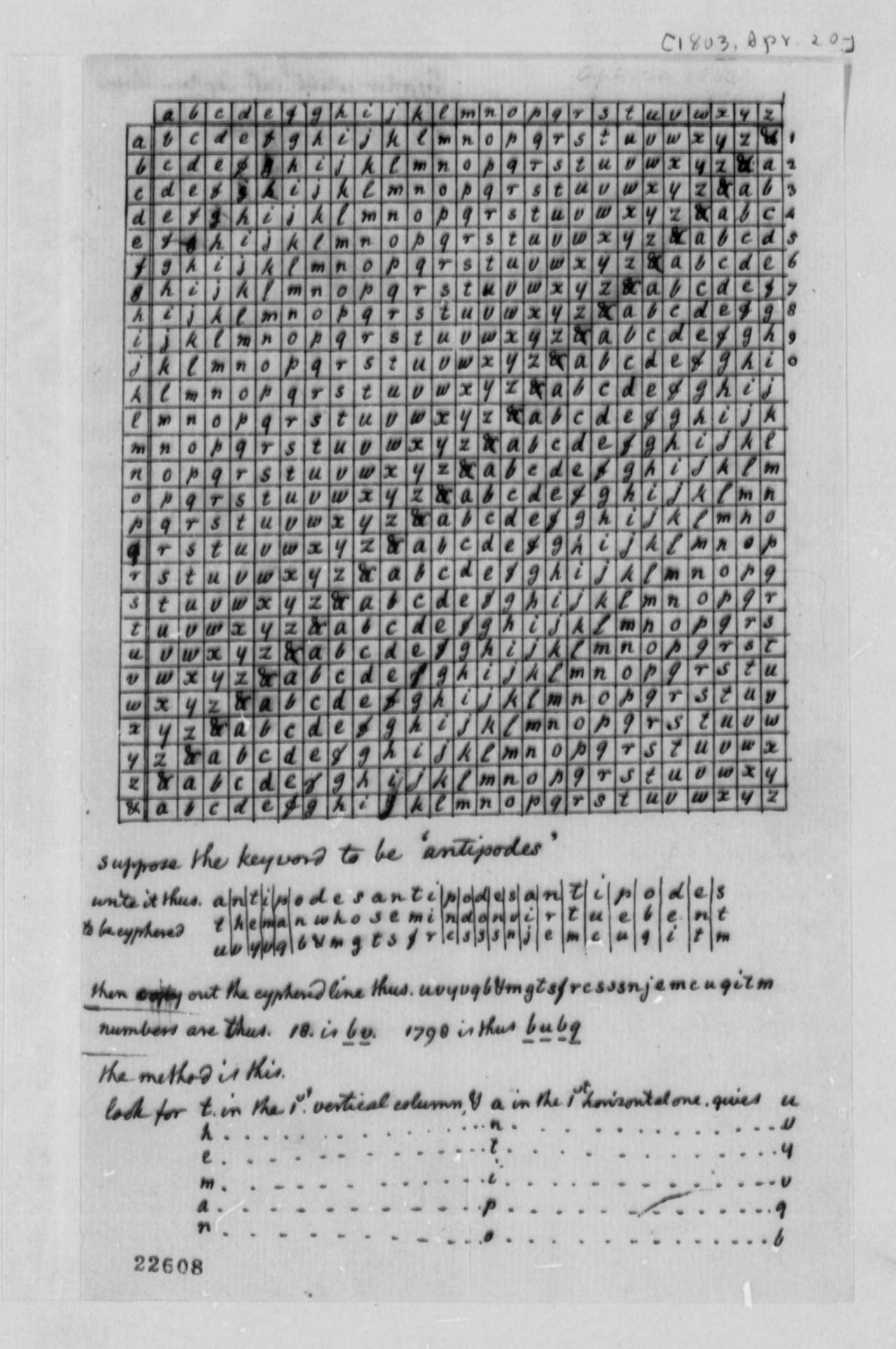

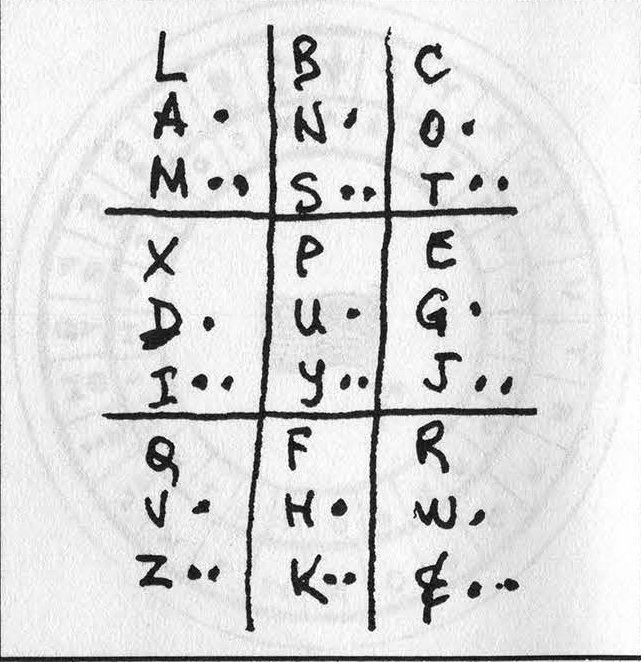

Figure 1: Cipher devised by Jefferson for use by the Lewis and Clark expedition.

In action, the wheels were turned so that each adjacent wheel showed one letter of the plaintext message; when the plaintext was in place, the remaining 25 columns were available as ciphers, from which any one column could be chosen. The recipient of the cipher, using an identical device, arranged the wheels in cipher message sequence; the plaintext decipherment would then appear as one of the 25 remaining column.

A more detailed physical description of Jefferson's Wheel Cipher may be found in most books on cryptography, as well as in encyclopedias. There is no evidence that it was ever used by Jefferson himself; but it appeared in France many years later in a slightly different form, and after World War 1 it was reinvented in the United States, where it was known as the M-94.

In World War 2 the Germans produced the Enigma machine, similar in principle, which used electromechanical rotors (wheels) on each of which was a jumbled alphabet. In the same period the British invented a machine similar to the Enigma, which they called the Typex. The Japanese as well had a rotor machine, which the U.S. called by the name of Red. Moreover, the Japanese had a famous machine, called Purple, which used stepping switches instead of rotors but accomplished essentially the same task as all the others; thus, whether wooden wheels are used, or electromechanical rotors with bells and whistles, the underlying principle is Thomas Jefferson's, and each new variation gives honor to his original genius.

Thomas Jefferson had an eclectic intellect; today he would be a hacker of admirable versatility. A recent study of Jefferson by Silvio A. Bedini, Thomas Jefferson: Statesman of Science (published in 1990 by Macmillan - this book is a treasure and I recommend it to all hackers), abundantly demonstrates this eclectic quality that characterized his mind. Bedini's illuminating discussion of the Wheel Cipher, for example, shows that Jefferson's inspiration may have come from a brass cylindrical word-combination lock made in France. Bedini also shows a cipher devised by Jefferson for use by the Lewis and Clark expedition. Figure 1 is a copy of this cipher.

What is particularly interesting is that the table shown here contains not 26 but 27 characters, the 27th being an ampersand ("&"). Practically none of the existing writings on cryptography show this cipher, but I show it because it is interesting and because it does not limit the alphabet to 26 characters.

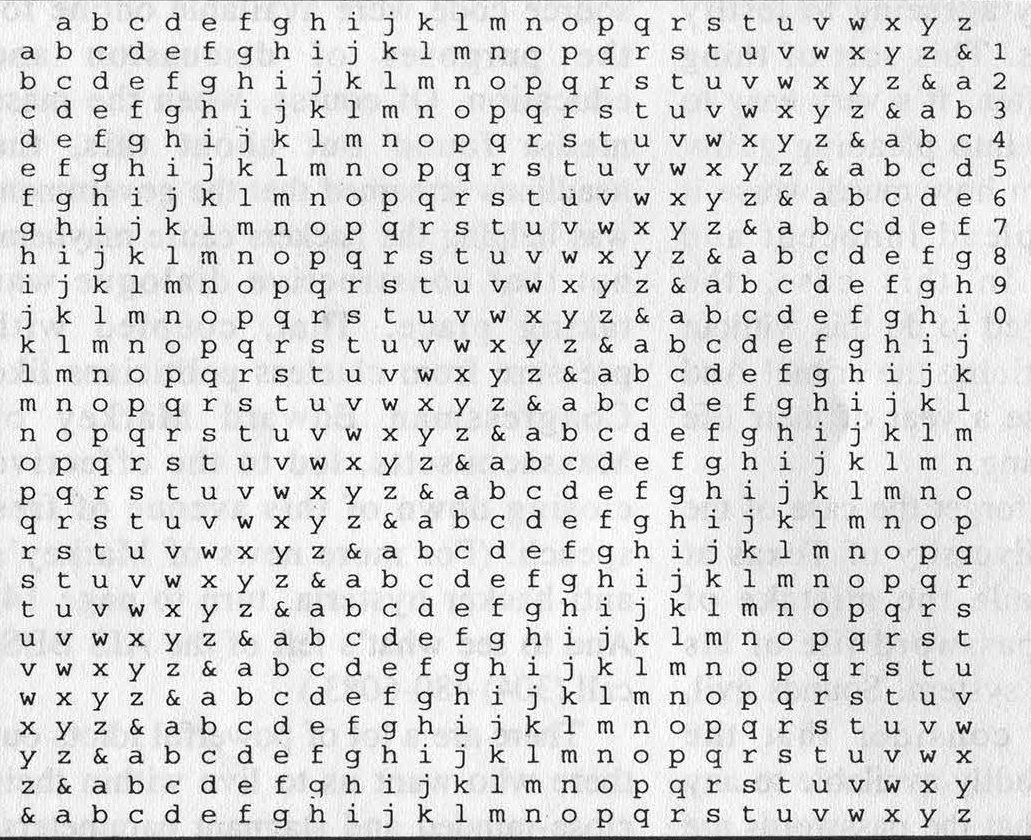

Figure 2: Peter Rabbit's cipher disk.

Figure 2 shows the same cipher converted (for the first time, by Peter Rabbit) into a cipher disk, consisting in reality of a stationary outer disk and a movable inner disk printed on cardboard stock. An American Flag lapel pin (a patriotic relic of Desert Storm) serves to hold the two disks together.

The disk is used as follows:

The arrow index mark points to a letter of the key located on the inner disk - for example, "A" of the keyword: ANTIPODES

The plaintext, which in Jefferson's example is THE MAN WHOSE MIND ON VIRTUE BENT, is located on the outer disk; "T", the first letter, is then enciphered as "U" and so on, as directed in Figure 1.

Decipherment is the reverse of the same process. The cipher disk of Figure 2 is equivalent to the cipher table in Figure 1 and may be used in place of it.

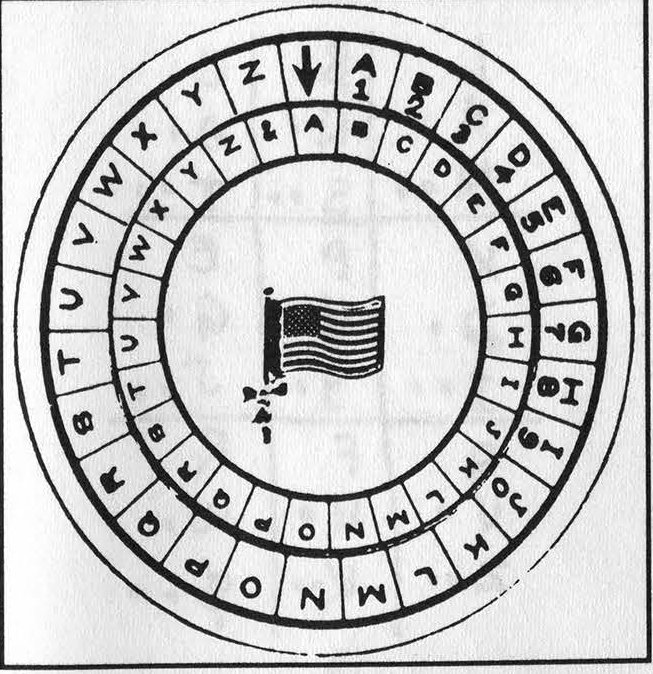

What is particularly interesting about the ampersand in Figure 1 is this: it is found in a little-known cipher disk devised by a 15th-century Italian polymath named Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti's disk is shown in Figure 3. Shown at its upper-right is an enlarged section, the bottom cell of which contains the symbol "Et", the Latin word for "and", which ultimately became the ampersand symbol. Since the alphabet was not yet fixed in the 15th century, it was possible for the "Et" symbol to become considered as another alphabetic character. The fact that the source of the ampersand is so old shows once again the questioning eclecticism of Jefferson's mind.

Figure 3: Leon Battista Alberti's cipher disk.

Jefferson's Lewis and Clark cipher is still useful today. To put it into operation one should first modify the inner disk in Figure 2 to show a 27-character jumbled alphabet similar to the one Alberti used, shown in Figure 3, that will reduce the obvious periodicity of the cipher. Second, one should not use a short key that is repeated again and again, but rather a long key with no repetitions, a key that is as long as the message to be enciphered.

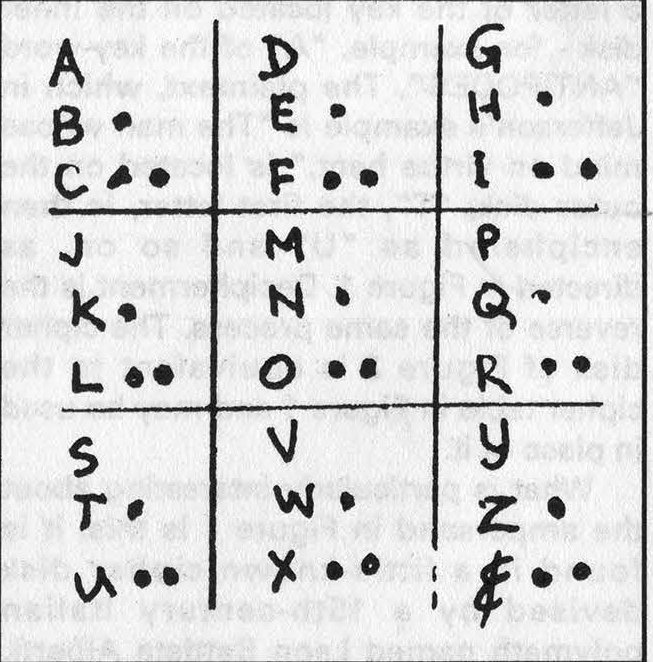

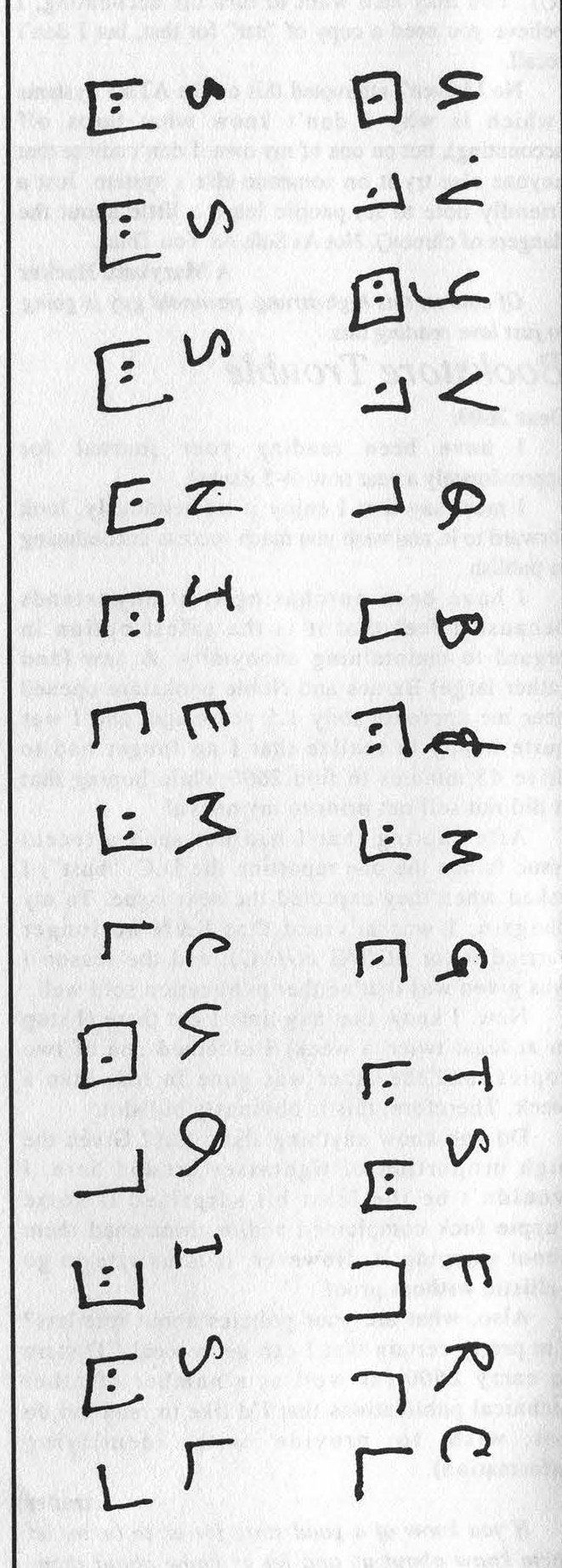

Finally, a Jeffersonian twist can be put on one of the favorite ciphers used by students both past and present: the pigpen cipher. The pigpen traditionally has only 26 letters; however with the addition of an ampersand, it becomes a 27-character cipher.

Figure 4a: Pigpen cipher.

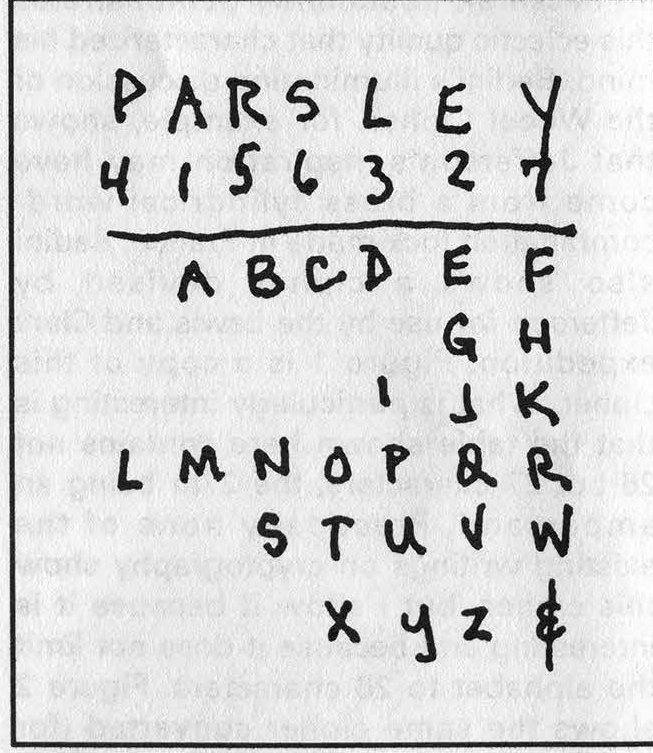

This is shown in Figure 4a. Next, the 27 characters can be jumbled with a keyword - for example, PARSLEY (see Figure 4c).

Reading the now-jumbled alphabet as a columnar transposition from left-to-right, one gets the following:

Figure 4b: Pigpen cipher.

LAMBNSCOTXDIPUYEGJOVZFHKRW& |

This alphabet is shown in Figure 4b.

Figure 4c: Columnar transposition.

(Editor's Note: Assign numbers based upon the letters' position in the alphabet. For example 'P' is 4 because it is fourth in line alphabetically. The alphabet below the line reads left-to-right; the horizontal lines are analogous to the vertically numbered columns.)

Returning now to Jefferson's Lewis and Clark cipher, one re-enciphers it using the pigpen cipher equivalents shown below in order to obtain the pigpen cipher as shown in Figure 4d. The alphabetic letters absorb the ampersand, which has now become one of the 27 diagrammatic symbols.

Figure 4d