How Viruses Work

By Neil Randall, PC Magazine

Understanding how viruses work is the first step in defending against them.

If you buy a new computer these days, it's likely to ship with an antivirus package. This fact, more than anything else, should convince us of how widespread viruses have become and how much the computer industry has come to accept their inevitability. Quite simply, viruses are a fact of computing life.

There are thousands of viruses out there and many different categories of virus, but generally they all fit a single basic definition. A virus is a computer program intentionally designed to associate itself with another computer program in a way that when the original program is run, the virus program is run as well, and the virus replicates itself by attaching itself to other programs. The virus associates itself with the original program by attaching itself to that program or even by replacing it, and the replication is sometimes in the form of a modified version of the virus program. The infected program can be a macro, and it can be a disk's boot sector, the very first program loaded from a bootable disk.

Notice the "intentionally designed" part of the definition. Viruses aren't just accidents. Programmers with significant skills author and develop them, then find ways to get them onto the computers of the unsuspecting. And the stronger antivirus programs get, the harder virus authors work to get around them. For many virus authors, the whole thing is simply a challenge; for others, the point is having a good time making computing life uncertain or even miserable. Too bad: They could make gobs of money solving the Y2K crisis instead.

Viruses have quite correctly gained a reputation for being harmful, but in reality many are not. Yes, some damage files or perform other forms of destructiveness, but many are simply minor annoyances or are even invisible to most users. To be considered a virus, a program need only replicate itself; anything else it does is extra.

Even relatively pain-free viruses aren't completely harmless, of course. They consume disk space, memory, and CPU resources and therefore affect the speed and efficiency of your machine. Furthermore, the antivirus programs that sniff them out and eliminate them also consume memory and CPU resources; many users, in fact, claim they slow the computer down noticeably and are more intrusive than the viruses themselves. In other words, viruses affect your computing life even when they're not actually doing anything.

Viruses and Virus-like Programs

The above explanation of viruses is actually more specific than the way we tend to use the term virus. Other types of programs exist that fit only part of that definition. What they have in common with viruses is that they act without the user's knowledge and commit some kind of act inside the computer that they are intentionally designed to do. These types include worms, Trojan horses, and droppers. All of these programs, including viruses, are part of a category of program known as malware, or malicious-logic software.

A worm is a program that replicates itself but doesn't infect other programs. It copies itself to and from floppy disks or across network connections, and sometimes it uses the network in order to run. One type of worm--the host worm--uses the network only to copy itself onto other machines, while another type, the network worm, spreads parts of itself across networks and relies on network connections to run its various parts. Worms can also exist on a nonnetworked computer, in which case they can copy to various locations on your hard disks.

The name Trojan horse comes from the Greek myth, best recounted in The Odyssey, in which the Greek army left a wooden horse as a gift to the Trojans, hiding troops inside the horse as it was taken into Troy. The Greeks jumped out and captured the city, ending the long siege. The idea in computers is the same. A Trojan horse is a program that is hidden inside a seemingly harmless program. When that program is run, the Trojan horse launches in order to perform actions that the user doesn't want. Trojan horses do not replicate themselves.

Droppers are programs designed to avoid antivirus detection, usually by encryption that prevents antivirus software from noticing them. The typical functions of droppers are transporting and installing viruses. They wait on the system for a specific event, at which point they launch themselves and infect the system with the contained virus.

Related to these programs is the concept of the bomb. Bombs are usually built into malware as a means of activating it. Bombs are programmed to activate when a specific event occurs. Some bombs activate at a specific time, typically using the system clock. A bomb could be programmed to erase all DOC files from your hard disk on New Year's Eve or pop up a message on a famous person's birthday. Others are triggered by other events or conditions: A bomb might wait for the twentieth instance of a program launch, for example, and erase the program's template files. Viewed this way, bombs are just malicious scripts or scheduling programs.

Viruses can be thought of as special instances involving one or more of these malware programs. They can be spread through droppers (although they need not be), and they use the worm idea to replicate themselves. While viruses are not technically Trojan horses, they act like them in two ways: First, they do things the user doesn't want; second, by attaching themselves to an existing program, they effectively turn the original program into a Trojan horse (they hide inside it, launch when it launches, and commit unwanted acts).

How a Virus Works

Viruses work in different ways, but here's the basic process.

First, the virus appears on your system. It usually enters as part of an infected program file (COM, EXE, or boot sector). In the past viruses traveled almost exclusively through the distribution of infected floppy disks. Today, viruses are frequently downloaded from networks (including the Internet) as part of larger downloads, such as part of the setup files for a trial program, a macro for a specific program, or an attachment on a e-mail message.

Note that the e-mail message itself cannot be a virus. A virus is a program, and it must be run to become active. A virus delivered as an e-mail attachment, therefore, does nothing until you run it. You run this kind of virus by launching the attachment, usually by double-clicking on it. One way to help protect yourself from this kind of virus is simply never to open attachments that are executable files (EXE or COM) or data files for programs, such as office suites, that provide macro-writing features. A graphics, sound, or other data file is safe.

A virus starts its life on your PC, therefore, as a Trojan horse-like program. It is hidden within another program or file and launches with that file. In an infected executable file, the virus has essentially modified the original program to point to the virus code and launch that code along with its own code. Typically, it jumps to the virus code, executes that code, and then jumps back to the original code. At this point the virus is active, and your system is infected.

Once active, the virus either does its work immediately--if it's a direct-action virus--or sits in the background as a memory-resident program, using the TSR (terminate and stay resident) procedure allowed by the operating system. Most are of this second type and are called resident viruses. Given the vast range of activities allowed by TSR programs--everything from launching programs to backing up files and watching for keyboard or mouse activity (and much more)--a resident virus can be programmed to do pretty much anything the operating system can do. Using a bomb, it can wait for events to trigger it, then go to work on your system. One of the things it can do is scan your disk or (more significantly) your networked disks for other running (or executable) programs, then copy itself to those programs to infect them as well.

Virus Types

Virus authors are constantly experimenting with new ways to infect your system, but the actual types of virus remain few. These are boot sector viruses, file infectors, and macro viruses. There are different names for these types and some subtypes, but the idea remains the same.

Boot sector viruses or infectors reside in specific areas of the PC's hard disk, those that are read and executed by the computer at boot time. True boot sector viruses infect only the DOS boot sector, while a subtype called the MBR virus infects the master boot record. Both of these areas of the hard disk are read during the boot process, during which the virus is loaded into memory. Viruses can infect the boot sectors of floppy disks, but typically a virus-free, write-protected boot floppy disk has always been a safe way to start the system. The problem, of course, is guaranteeing that the floppy disk itself is uninfected, and that's a task that antivirus programs attempt to do.

File infectors, also called parasitic viruses, are viruses that attach themselves to executable files, and they are the most common and the most discussed. Such a virus typically waits in memory for the user to run another program, using such an event as a trigger to infect that program as well. Thus they replicate simply through active use of the computer. There are different types of file infectors, but the concept is similar in all of them.

Macro viruses, a relatively new type, make use of the fact that many programs ship with programming languages built-in. The languages are designed to help users automate tasks through the creation of small programs called macros. The programs in Microsoft Office, for instance, ship with such a built-in language, and in fact it provides many of its own built-in macros. A macro virus is simply a macro for one of these programs, and indeed this type of virus became known through its infection of Microsoft Word. When a document or template containing the virus macro is opened in the target application, the virus runs and does its damage. In addition, it is programmed to copy itself into other documents, so that continual use of the program results in continual spread of the virus.

A fourth type, called multipartite, combines boot sector infection with file infection.

For a huge listing of viruses along with explanations of what they do, see the Virus Encyclopedia section of Symantec's AntiVirus Research Center.

Smarter and Smarter

The macro virus concept works because the programming language provides access to memory and hard disks. So, in fact, do other recent technologies, including ActiveX controls and Java applets. True, these are designed to protect the hard disk from the virus program (Java better than ActiveX), but the fact is that these programs can install themselves on your computer simply because you visit a Web site. Obviously, as we become increasingly networked and as we expect such conveniences as operating-system upgrades over the Internet (Windows 98 and NT 5 both do this), we put ourselves at greater risk from viruses and other malware.

Virus authors are nothing if not innovative, and they constantly come up with new ways of thwarting antivirus software. Stealth viruses, for example, mislead the antivirus software into thinking that nothing is wrong. Essentially, a stealth virus retains information about the files it has infected, then waits in memory and intercepts antivirus programs that are looking for altered files. It gives the antivirus programs the old information rather than the new. Polymorphic viruses alter themselves when they replicate, so that antivirus software that looks for specific patterns won't find all instances of the viruses; those that survive can continue replicating. Several other types of smart viruses are appearing regularly, as the game of cat and mouse between virus authors and antivirus software producers continues. In all likelihood, viruses are here to stay.

Some common viruses.

| Name | Type | What it Infects | What it Does |

| Aol4free.com | Trojan horse | Nothing (causes harm but does not spread to other programs) | When run, uses Deltree command in DOS to erase hard disk; different from the Aol4free virus hoax which predates it. |

| Form | Resident boot sector | Floppy disk boot sector | Fairly old but very common; causes clicking sound when key is pressed. |

| Hare | Resident polymorphic multipartite | COM, and EXE files, master boot record, floppy disk boot sectors | Activates on August 22 and September 22; attempts to erase A:, B:, and C: drives. |

| Java.App Strange Brew | Direct-action file infector | Java.class files | First virus to infect Java apps; because it affects Java, it can spread across operating systems. No known damage. |

| Microsoft.Excel. Spellcheck | Macro | Excel spreadsheets | Creates file Spellck.xla in Excel startup directory; harmless by itself but displays messages warning of macro viruses. |

| Monica (Hanko.4167) | Resident stealth file infector | COM, EXE files | Halts the computer at 7:07 on July 7 (7/7/7:07) and displays "Monica" message. |

| W95.CIH | Resident file infector | Windows 95 EXE files | Triggered on the 26th of the month; attempts to overwrite the flash BIOS and to corrupt hard disk data. |

| W95.Marburg | Direct-action file infector | Windows 95/98 and NT application files (several types) | Three months after first infection, when an infected application is launched, covers screen with Windows error icons; also erases anti-virus software. |

| W97/X97M Shiver | Macro | Word 97 and Excel 97 documents | First macro virus to infect both Word and Excel files; prevents loading of infected documents. |

| Win32/Semisoft | Resident file infector | Windows EXE files | Sends information from several files on the hard disk to specific IP addresses. |

| WM.PolyPoster | Macro | Word documents | Posts message to certain newsgroups using Free Agent newsreader; message includes Word document as attachment. |

| XM.Compat | Polymorphic macro | Excel spreadsheets | Triggered after August 31, 1998, when closing infected spreadsheet, randomly selects numeric cell and changes the value in that cell by fiver percent. |

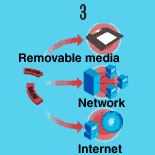

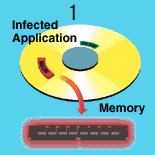

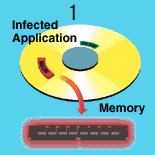

How a Common Virus Spreads

1. An application infected with a common virus loads into memory. Even when the application terminates, the virus remains in memory.

2. The virus infects one or more other applications. Some viruses use idle time to search for applications, while others infect applications as they are loaded into memory.

3. These virus-infected applications can then be transmitted via removable media,

a network, or the Internet.