Hackers If you had the power to break into some computer files, what would

you do? Change your grades, erase some library fines, or maybe add a few

zeros to your bank account? For some computer hackers, that's only the

beginning. They can crack code and steal big money, even threaten our

national security. Alberto Rosas reports on the growing computer

underworld.

If you had the power to break into some computer files, what would

you do? Change your grades, erase some library fines, or maybe add a few

zeros to your bank account? For some computer hackers, that's only the

beginning. They can crack code and steal big money, even threaten our

national security. Alberto Rosas reports on the growing computer

underworld."As the world moves into cyberspace and as all money flows into cyberspace, well, crime follows money and you're going to see it there," says Richard Power of the Computer Security Institute. And as the Internet expands, the opportunity to make illegal profit grows with it. Thousands of cyber-criminals are taking advantage of what is still mostly uncharted territory.

One 18-year-old broke into a financial institution, generated a credit card for himself, and went on a vacation to Hawaii. Other people have been known to try and find ways to hack and counterfeit lottery tickets. And in one case, a gang of international crackers broke into Citibank's wire transfer software and stole 2.8 million dollars. But not everyone hacks for profit. In fact, those who do are called crackers. But hackers crack code simply for the challenge.

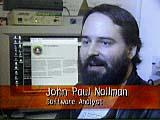

"It's knowledge," says software analyst John Paul Nollman. "It's the

excitement of learning things. You don't really see people in the hacker

community who

The sport of hacking involves breaking into a protected computer file, taking a look around, and maybe even leaving a calling card. "Maybe they just want to put their name in the Message of the Day when you log in or something," adds Nollman. "It's real simple. It's getting in that's interesting. It's not what you do in there, it's not what you don't do in there, it's just the act of getting in."

But all files are not created equal. The prized sites for a hacker are

the CIA, the FBI, and the Pentagon. "The harder it is to discover that

information, the more interesting it is to them," says Nollman. "If you

go and publicize a

And the Pentagon does seem to entice people to break in. Just in the past year, there were over two hundred thousand break-in attempts. Not everyone gets caught, but some who tried too hard found the FBI on their doorstep. You wouldn't think the FBI would track down some hackers in sleepy Cloverdale, California, but hackers are everywhere. They call themselves Makaveli and Too Short, and claim to have broken into hundreds of servers run by the Pentagon. It's a job so extensive that one federal official called it the most organized and systematic attack ever discovered. "I think this was, more than anything, a serious wake-up call," says Deputy Defense Secretary John Hamre.

The FBI raided their homes last month, armed with search warrants possibly

A classmate describes one of the hackers as "kind of reserved...not as open as other kids. The main thing he likes to do is get on the computer and go crazy with this stuff." During the day, Makaveli and Too Short used their skills to build Cloverdale High's computer network. "They're good kids," says teacher John Hudspeth. "They've helped me out a lot this summer, and they're always there to help out in the lab when I need help." But at night they were logging hundreds of hours online cracking codes. According to the Pentagon, they didn't damage any files. So why did they do it? In an interview with an online publication, Makaveli said, "It's power dude. You know power."

Shipley knows the thrill of hacking. When he was a teen, he almost went to the other side of the law. Now, he's a computer security expert. "When Russell first met me, I was still borderline," says Shipley. "When I first met Peter, I had a lot of concern that he would end up in jail," says Russell Brand. Today, Shipley and Brand keep the computer files of major corporations safe from hackers. In fact, Shipley still hacks to keep up-to-date on new break-in techniques. Today, he's war dialing. "I'm calling sequentially each phone number in the local dialing range and finding which ones have computers attached to them," he explains. He can't break in without a password, but there's a way around that. "You test each word in the dictionary against the password," says Shipley.

And Shipley insists that while there is some corruption, most hackers don't deserve the bad rap: "There are lots of amateur radio enthusiasts, there are lots of amateur chemists in the world. There are lots of amateur machinists in the world, and people don't worry about [them] going out and building a bigger canon and killing people. Same thing. Hackers aren't going to go out there and write a virus to kill people." Even so, he still takes precautions. "I know a lot about security. I know how to break in. I know how to obtain your credit reports. I guard my own," he says. It turns out that Makaveli and Too Short weren't acting alone. Just last week, the FBI arrested their ringleader -- a hacker named Analyzer who was operating out of Israel. For more information about Peter Shipley, check out these sites: http://www.network-security.com and http://www.dis.org/shipley/.

|

"Hackers can do just about anything they want to do," says Keith Lowrey,

San Jose Police Department. "They can alter your credit, they can steal

your identity."

"Hackers can do just about anything they want to do," says Keith Lowrey,

San Jose Police Department. "They can alter your credit, they can steal

your identity."  don't have this passion for going out and finding things out, finding

out all sorts of information, especially information that we're not

supposed to know."

don't have this passion for going out and finding things out, finding

out all sorts of information, especially information that we're not

supposed to know."  machine that has a name like topsecret.pentagon.gov, of course it's going to attract attacks."

machine that has a name like topsecret.pentagon.gov, of course it's going to attract attacks."  linking them to break-ins of at least eleven military computer systems.

But Makaveli and Too Short are just high school students, and no one

suspected them capable of a federal crime.

linking them to break-ins of at least eleven military computer systems.

But Makaveli and Too Short are just high school students, and no one

suspected them capable of a federal crime.  "Most hackers out there are...trying to gain admiration. They break into something, they brag about it," says Peter Shipley.

"Most hackers out there are...trying to gain admiration. They break into something, they brag about it," says Peter Shipley.  These days, he only breaks in to other systems when authorized by clients. "I professionally break into corporations," he adds.

These days, he only breaks in to other systems when authorized by clients. "I professionally break into corporations," he adds.