MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 10 : THE HELLENES -

CLASSICAL GREECE

The Greek peninsula, and its northern borders, the Balkans, had previously been settled by the original European peoples during the Neolithic Age. These peoples had created the Old European civilizations, which were some of the most advanced in Europe at the time.

From approximately 5000 BC onwards, the Indo-European peoples had started flooding westwards, at first conquering but then integrating with these original Old European peoples.

This massive influx of peoples brought about the fall of these Old European civilizations - and in their place arose the two great civilizations which have come to epitomize the classical world: Greece and Rome.

MYCENAE AND DORIANS - FOUNDERS OF ATHENS AND SPARTA

The first of these new great peoples was the Mycenean civilizations, started around the year 1900 BC. The Myceneans were however dispersed by yet another Indo-European invasion, that of the Dorians. The Myceneans settled in large numbers on islands off the present day Turkish coast, establishing what became known as Ionia and the Ionian civilization. The Dorians established their capital city at Sparta, a city which, along with Athens, was to become synonymous with the history of Classical Greece.

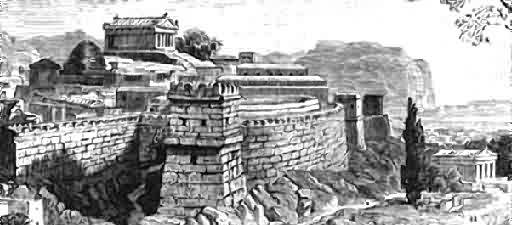

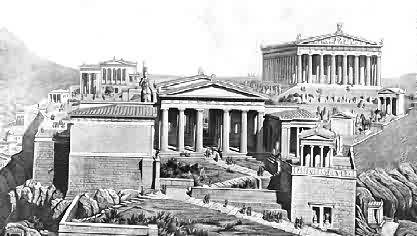

The citadel of Mycenae, reconstructed to what it looked like at its height. The genesis of Classical Greek culture was born and nurtured here, one of the earliest Indo-European invasions of the Grecian lands.

By approximately 1000 BC, the waves of invading Indo-Europeans had started to come to an end, and a semblance of stability returned to central and western Europe. Together with the original European peoples, the new Nordic settlers built upon the Old European civilizations, with the first great "city states" being built on the Greek peninsula.

HELLENIC AGE 800 BC - 400 BC

The four hundred years stretching from 800 BC to 400 BC are known as the Hellenic Age, and mark the height of classical Greek civilization. Around this time the Greeks also founded the city of Byzantium, later to become famous as Constantinople and today called Istanbul.

It was only the later Romans who called the inhabitants of this region Greeks - they referred to themselves as Hellenes, hence the Hellenic Age.

Nordic racial types in original Classical Greek sculpture: on the left, the head of a victor in the Olympic Games; center, the Greek leader Menelaus; and right, the goddess Aphrodite.

IDEOLOGICAL DIVISION - OLIGARCHY VERSUS DEMOCRACY

A knowledge of the nature of the city state is crucial to an understanding of the history of Classical Greece. Far from being an united people, the Greeks established themselves in walled, fortified and quite often self sustaining cities, each being fiercely independent and seemingly wont to go to war with each other at the proverbial drop of a hat.

By 750 BC, two distinct ideologies had formed amongst the Greek city states. The first was an oligarchy: - ruled by an educated elite. The second was a limited form of democracy - rule by the masses.

The city of Sparta was the leading exponent of the oligarchical system, with the city of Athens being the leading exponent of the democratic system. Four city states in particular achieved prominence: Sparta, Corinth, Athens and Thebes. The last three of these cities were plagued by political uncertainty for long periods, with government forms alternating between democracies, monarchies and oligarchies.

Sparta was the only exception to this variance in political form: throughout it steadfastly remained a relatively stable oligarchy, and actively despised the democracies.

SPARTA AND RACE - WORLD'S FIRST EUGENICS

The Spartans themselves kept their society strictly divided into three classes: by blood. At the top were the Spartans themselves, nearly all Nordic, ruled by their king.

The middle class comprised mainly of the original Greeks and some later descendants of other Indo-European invaders (such as the Dorians). This middle class tended to be less Nordic in appearance than the Spartans themselves.

The lowest class of Spartan society were the darkest in the society, called helots, who were mainly original Mediterranean racial types who had mixed with North African (Arabic, Nubian and Semitic) slaves imported into the region at an earlier date.

The Spartans devoted themselves full time to military and physical training. Every Spartan man was a lifelong soldier, never taking part in any other function of society. The middle classes undertook all the commercial activity in Spartan society, while the lowest classes did the manual labor. The existence of this full time and fully trained professional army class was unique in history, and the city of Sparta was the only Grecian city which did not have city walls - so feared were the Spartan soldiers, that none deemed it wise to attack the city.

The Spartans also practiced a crude form of racial eugenics (improvement of the racial line) - allowing only the best and perfect specimens amongst them to survive to adulthood. All new babies were examined by a council of elders and any mentally retarded or severely deformed children were deliberately left to die.

The Spartans also regularly engaged in what was known as

the crypteria - the wholesale slaughter of hundreds of helots at a time, officially

recorded as a necessary measure to preserve their society.

In addition, Spartan laws dictated heavy penalties for celibacy and late marriage, and

exempted those from taxes who had more than four children.

The end effect of all these measures was a gradual Nordicization of Spartan society. This process was however to run out of steam as the warlike nature of the Spartans finally whittled away their warrior class, many being killed in battle before having time to procreate in sufficient numbers to keep up a steady population growth.

So weakened, the Spartans were to be finally overrun by an Indo-European people from north Greece, the Macedonians. Thus the Spartans are virtually unique in that they did not disappear through racial integration, but rather through self extermination in endless wars.

Although not as formally defined, more or less the same racial class mix prevailed in virtually all of the southern Greek city states, with the lowest (and darkest) classes always being the numerically superior group - and also being continually supplemented by the importation of slaves and laborers from other territories which from time to time fell under the sway of the various city states.

ATHENS - EVOLUTION OF GOVERNMENT

Athens passed first through a period of oligarchy, then into autocracy and finally into a limited democracy. There was however no standing army although the Athenians could, once mobilized, put a very powerful military force into the field.

The two ideological systems which prevailed in the different city states - oligarchy and democracy - came into direct conflict with one another - and this conflict played a major role in destroying the power of classical Greece, although the final blow which caused the disappearance of Classical Grecian power was once again, the infusion of foreign blood.

The influx of Nonwhite foreigners into Classical Greece came about through the large scale colonization of neighboring territories. Although some territories upon which Greek colonies were established, had racially compatible natives (such as the then population of southern Italy - different from that residing there today - and the Mediterranean coast of France and eastern Spain) - many were however not compatible at all.

The importation of slaves into mainland Greece from areas such as Asia Minor, North Africa and other parts of the Middle East started and continued unabated between the years 700 BC and 500 BC - all of which ultimately left their mark upon a significant section of the Greek population of the time.

Originally the Classical Greeks prided themselves upon possessing the "fairest eyes . . . of all the nations" or so wrote the Jewish physician and sophist Adamantious during the 4th Century AD (Physiognomiminica, iii. 32).

As the darker elements in Grecians society grew in number, so did the desire to mimic the original Nordic blonde haired type. The Greek writer Euripides for example wrote a tract on how hair could be dyed blonde.

This is not however to say that the Classical Greeks did not do enough damage to themselves by constant fighting with other Whites and themselves, with the first of these great and lingering conflicts being with the Persians.

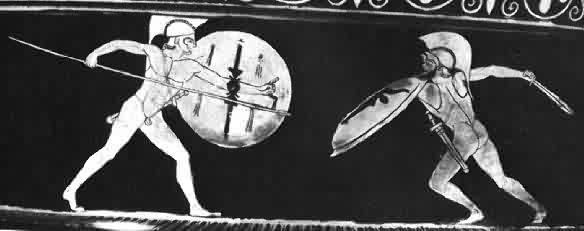

A splendid original statue of an Athenian soldier in full battle dress. Soldiers such as this fought both the Greek/Persian and the Inter-Greek Wars from 490 to 404 BC.

THE ATHENIAN WARS WITH PERSIA 490 - 480 BC

The originally Indo-European Persians had started expanding their empire around 550 BC - and this expansion westward included occupying the Ionian city states, founded by the remnants of the Mycenean peoples.

After the Persian King, Darius I, ascended to the throne, the Ionians rebelled and re-established their independence and for five years, from 499 BC to 494 BC, the Ionians held out against the Persians.

The Persians did however reconquer Ionia and as punishment, destroyed the largest city in that region, Miletus.

During the Ionian rebellion the city state of Athens had sent material aid to Ionia, and this act led to the Persians deciding to punish the Athenians. Thereafter followed two Persian invasions of the Greek mainland, in 490 BC and 480 BC respectively. The first Persian invasion force was however defeated at the battle of Marathon and the invaders were forced to retreat and wait another ten years before re-launching their forces.

THERMOPYLAE - LEONIDAS' HEROIC STAND

The second invasion began when the Persian king Xerxes I in 481 BC, brought together one of the largest armies in ancient history, crossing the Bosporus strait over a bridge made of boats.

The Greeks met the Persian army in 480 BC at Thermopylae, where the Spartan leader Leonidas I and several thousand soldiers heroically defended a narrow pass.

A treacherous Greek showed the Persians another path that enabled the invaders to enter the pass from the rear. Leonidas permitted most of his men to withdraw, but he and a force of 1,400 Greeks fought until they were all killed by the overwhelmingly numerically superior Persian force.

The Persians then proceeded to Athens, capturing and burning the abandoned city. The Persian fleet then set sail after the Greek fleet, meeting them in battle off the island of Salamis near Athens. This battle, which saw over 700 ships from both sides engage one another for virtually an entire day, ended in defeat for the Persians. The Persian King, who had watched the battle from a golden throne on a hill overlooking the scene, fled back to Persia.

In the following year, 479 BC, the remainder of the Persian ground forces in Greece were beaten at the battle of Plataea.

In 478 BC a large number of Greek states formed a voluntary alliance, the Delian League, to drive the Persians from the Greek cities and coastal islands of present day Turkey. Athens, its status amongst the Greek city states enhanced by the victory at Salamis and Plataea, led the alliance. The victories of the League resulted by the year 466 BC in the liberation of the Ionian islands from Persian rule.

PERICLEAN GOLDEN AGE - VOTE BASED ON BLOOD

From the years 460 BC to 429 BC, Athens and many Grecian cities went through what is now known as its Golden Age.

Athens was under the leadership of an immensely popular leader named Pericles, who, although a democrat (in the limited Athenian sense of the word - only adult males of a certain class were allowed to vote), was most certainly under no illusion of the potential threat to his society posed by the influx of Nonwhite peoples.

In 451 BC, Pericles enacted a law limiting Athenian citizenship by biological descent - only those born of an Athenian mother and an Athenian father could be citizens - in other words voting rights were granted on the basis of blood only.

Left to right: Pericles of Athens, original Greek sculpture; Sophocles of Athens, original Greek sculpture; Zenon of Cyprus, founder of the Stoic philosophy, original Greek sculpture.

During the time of Pericles, Classical Greece reached the heights for which it is remembered today: it was at this time that the Olympic Games were established and held every four years at Olympus in honor of the god Zeus, lasting in that form until the year 394 AD.

During these celebrations, virtually all the Grecian city states sent athletes to Olympus, and any wars that might have been proceeding at the time were temporarily halted for the games.

Another of Pericles' achievements was the construction of the Parthenon on the acropolis in Athens, built from 447 BC to 432 BC and dedicated to that city's patron goddess, Athena Parthenos. This monument still stands today as a world famous beacon of Classical Greece.

The Parthenon, Athens, 447-438 BC, as it is today, and below, The Acropolis as it appeared during Athen's golden age. Pericles, Athen's greatest ruler, and Phidias, her greatest architect, raised the city to such heights that her sheer aesthetic beauty has been unsurpassed to this very day. When the Romans finally occupied Greece - long after the latter's collapse - they were in awe of the sheer splendor and beauty of Athens, and took much of their architecture and artistic style direct from Classical Greece.

THE INTER-GREEK WARS 431 BC - 404 BC

The wars between the Greek city states, known as the Peloponnesian Wars, (named after the peninsula) were the immediate cause of the collapse of the military might of Classical Greece.

After the end of the Persian wars, Greece had divided into two alliances - the Spartan League (mostly monarchies or oligarchies led by the city Sparta) and the Athenian empire (mostly democracies led by the city Athens).

Internal politicking, jealousy, general mistrust and the conflict between democracy and oligarchy led to the outbreak of war between the two alliances.

The first phase of the war was inconclusive, as although the Spartans had a strong land force, the Athenians were most powerful at sea. The city state of Athens was furthermore protected by massive and well built fortifications, which included the "Long Walls" - an incredible set of approximately seven mile long walls lining a single road linking Athens with its major port, Piraeus, through which the Athenian navy could keep the city supplied in times of siege.

In 430 BC, a plague broke out in Athens and a quarter of the population, including Pericles, died. The Spartan League also suffered as the plague spread, and by 421 BC both sides were exhausted. A peace treaty was signed, but the peace was short-lived and a renewed conflict broke out in 415 BC, when the Athenians attempted an invasion of Sicily, where Spartan aligned colonies had been established.

The Persians, still smarting from their defeat at the hands of the Athenians in 480 BC, then intervened, offering the Spartans money and skills to build a fleet to match that of the Athenians, on condition that the Spartan League guaranteed the Persians a free hand in Ionia.

The Spartan League accepted and by 405 BC, the new Spartan fleet scored a decisive naval victory at a harbor called Aegospotami in Thrace. The Spartans captured 170 Athenian ships and took about 4,000 prisoners, a blow from which Athens could not recover. The Spartans then renewed their siege of Athens.

This time, without a fleet to supply the city, the will to resist collapsed and along with the spread of famine in 404 BC, caused Athens to finally surrender.

Two Greek soldiers in battle. The Inter Greek Wars, known as the Peloponnesian Wars (431 -404 BC) were fought between alliances led by Athens and Sparta respectively. The wars ended in defeat for Athens, and with Spartan rule extending all over Greece. The wars however had an important racial side effect - they dramatically reduced the number of Indo-European inhabitants of the land. This, combined with the importation of large numbers of mixed race slaves from the near East and Africa, contributed significantly to the collapse of Classical Greece.

The Peloponnesian wars were at an end, but they had exacted such a toll from all the Greek city states that the numbers of Whites had been significantly reduced. This, combined with physical integration with the imported mixed race slaves from the Middle East and Africa, was the primary cause of the collapse of Classical Greece.

By 400 BC, none of the formerly great city states could withstand the new power in the north, that of Macedonia. From this land was to emerge Alexander the Great, who conquered all the warring Grecian city states in 338 BC.

GREEK ACADEMIA

Great buildings are not the only legacy of Classical Greece. Between the years 700 BC to 400 BC, there were great philosophical, cultural and scientific achievements as well. Any review of Classical Greece is incomplete without an overview of these great works.

- Greek philosophy is today still held in high esteem. The father of philosophy was one Thales (636 BC - 546 BC) who lived in the Ionian city of Miletus. Thales was the first philosopher to offer an explanation of life in terms of natural causes, and not in terms of the whims of gods.

- The geometrician Pythagoras (582 BC-500 BC) came from Samos in Ionia, and is most famous for his geometric theory to do with the right angled triangles.

- Another group of philosophers came to be known as Sophists, teachers of debate known as rhetoric. The Sophists insisted that truth in itself was a relative concept and denied the existence of any universal standards. The most famous Sophist was Protarus (490 BC - 421 BC) from whose name the word "protagonist" originates.

From Left to right: Socrates: an Alpine Greek racial type, original Greek sculpture; Demosthenes of Athens, original Greek sculpture; Euripides of Athens, original Greek sculpture.

- In the fourth century a philosopher named Diogenes founded a school of philosophers known as the Cynics. They had no respect for rules and regulations of society and lived very simply. Diogenes lived this philosophy to the extreme, at one stage using a large storage jar as his home.

- The Stoic philosophers were named after the stoa (porch) where their founder, Xenon, taught. They believed that if people acted naturally they would behave well, because their nature was controlled by the gods.

- The most outstanding opponent of the sophists was the Athenian born Socrates (470 BC - 399 BC) who believed in and quested after an eternal truth. Unfortunately for him his quest eventually led to his enforced suicide after his fellow Athenians accused him of disobeying religious laws and of corrupting the youth.

- The greatest of Socrates' disciples was Plato (427 BC - 347 BC) who achieved immortality by writing the first systematic treatise in political science, The Republic. Plato saw society as being divided into three classes - bronze (the workers); silver (the middle class); and gold (the ruling class). Significantly, Plato was the first renowned philosopher to recognize race as a factor in the rise and fall of civilizations. In The Republic he stated that the first requirement of continued statehood was the necessity of retaining racial homogeneity.

- Plato's greatest pupil was in turn Aristotle (384 BC to 322 BC) who wrote well on a large number of topics including art, biology, mathematics, politics, logic and rhetoric. Aristotle also was the tutor of Alexander of Macedonia, who was later to become ruler of most of the known world in his short life.

- Hippocrates (circa 420 BC) was a brilliant physician who revised much of what was till then known about medicine. His Hippocratic oath is still used by doctors today as a code of professional ethics.

- Great Greek playwrights include Aeschylus (525 BC - 456 BC); Sophocles (496 BC - 406 BC) best known for his play Oedipus Rex, about a man who mistakenly marries his mother; Euripides (480 BC- 406 BC); and the comedian Aristophones (445 BC- 385 BC).

- One freed slave became famous as a story teller: Aesop, who lived in the fourth century BC, is best remembered for his collection of short stories, each with its own moral lesson.

Greek theater, Epidaurus, circa 350 BC.

THE GREEK GODS

Greek Mythology consists in essence of a number of stories about a variety of gods. The Greek beliefs had several characteristics in common with many other Indo-European pre-Christian religions: gods often resembled humans in form and showed human feelings and did not involve specific spiritual teachings. As the mythology had no holy book or defining manual, the interpretations and practice thereof also differed widely. In this mythology the gods lived on a holy mountain, Mount Olympus, and there lived in what was a fairly ordinary society with a strict hierarchical structure.

The main gods and their respective areas of responsibility reflect the very earthly nature of the religion as a whole:

The Greeks believed that the gods controlled all aspects of their lives, and that they as mortal beings were totally dependent upon the good will of the gods. Each city devoted itself to a particular god or group of gods, for whom temples were built. In this way Athena was protector of the city of Athens, and once a gold statue of her stood inside the Parthenon still visible on the Acropolis hill in that city.

There were other holy places - Delphi was a holy site dedicated to Apollo. A temple built at Delphi contained an oracle, or prophet, who claimed to be able to see into the future; a similar temple was built at Didyma in modern day Turkey.

Classical Greek religion was inherently Indo-European in origin, and many of their Gods had obvious parallels with other European religions. Here are the remains of the Temple at Delphi in Greece. Here was an oracle who - allegedly - could see into the future.

The most intriguing part of the Greek pantheon was that the gods, despite their superhuman powers, showed human foibles and errors of judgment - a strange mix of the supernatural and the very physical, showing clear similarities to the gods of the northern European Indo-European religions.

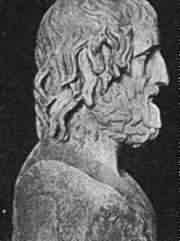

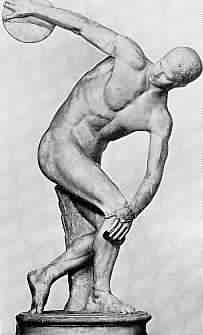

The Classical Greek emphasis on sport and physique is reflected in these famous statues: left, Discoblus: a Roman copy of a Greek original (Museo Nazionale Romanon, Rome); and right, Aphrodite of Cnidus, a Roman copy of a Greek original (Vatican Museum, Rome).

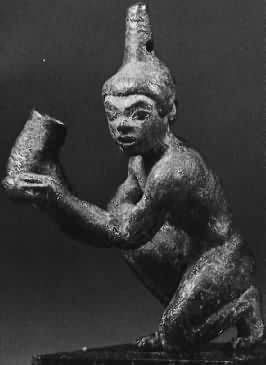

The downfall of Classical Greece - the importation of Black slaves. In this 300 BC Grecian statue, a Black African slave is shown polishing a boot. It was the importation of large numbers of racially foreign slaves which was to lead to the dissolution of the Classical Grecian civilization.

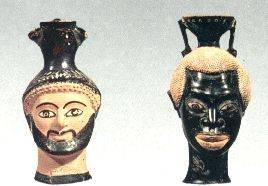

Below: Two pots, dating from the 5th Century BC, showing the racial type of slaves used in Ancient Greece: One is clearly Semitic and the other Black. These pots are on public display at the National Museum, Athens.

THE DARKENING OF GREECE - CITIZENSHIP TO FOREIGNERS

In 411 BC, forty years after Pericles had enacted his law limiting citizenship to those of biological Athenian descent only, the law was turned on its head and citizenship of Athens was given to tens of thousands of foreigners who had entered Athens, particularly from the Middle East, with the argument being used that the city state had to make up the huge population losses suffered as a result of the Persian and inter-Grecian wars.

By this stage the racial mix of Athens and many other Grecian city states was beginning to show the effects of the importation of peoples from elsewhere in the Middle and Near East, and significant sections of the population had become darker than even during Pericles' time.

This darkening of the population (caused partly by the Nordic and original European elements of Grecian society warring themselves to death - and partly by the importation of masses of already mixed Middle Eastern peoples) runs directly in tandem with the decline and fall of Classical Greece.

The gradual darkening of the Grecian peoples was noted by many famous Greek writers of the time. By drawing comparisons with the Greek peoples, the surrounding Nordic tribes were of fair complexion. Hippocrates makes reference in his works to the "long heads" (that is, Nordic skulls) of the Macedonians - while Aristotle made copious references to the fairness of the Scythians and the Macedonians.

The Greek soldier and historian Xenophon (430-354 BC) also made a point of referring to the blond haired and fair eyed Macedonians and Scythians in his book Anabasis, which described a Greek expedition against the Persians.

By the time of the Roman Emperor Octavian Augustus (who reigned directly after Julius Caesar), the Roman historian Manilius counted the Greeks as amongst the dark nations of the world, referring to the Greeks as part of the "colorate gentes" (Astrnomica, iv, 719.)

This process, which happened over a period of centuries, was to be aggravated by the Turkish invasion of Greece and the Balkans nearly 1,200 years later.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.