MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 12 : THE AGE OF THE CAESARS - PRE-CHRISTIAN ROME

The Italian peninsula had originally been settled by a Proto-Nordic/Alpine Mediterranean White racial mix during the Neolithic age, with the Alpine and Mediterranean elements being in the majority.

From around 2000 BC, Indo-European migrants from central Europe (and originally from southern Russia) settled in northern Italy, crossing the Alps from present day Austria and Hungary. Amongst these people were Celtic tribesmen known as the Latini. Racially speaking, these tribesmen were predominantly Nordic in nature. Another group of Whites, known as the Etruscans, also settled in Italy by the year 800 BC.

THE ETRUSCANS

The Etruscans were a mixture of the original Old European White sub-groupings, but were culturally and militarily superior to the original inhabitants of Italy. As a result, they soon grew to dominate the major part of northern Italy.

The Etruscans established an advanced society, building cities and settlements which were certainly far more advanced than anything else seen in the country till that time. However, the Etruscans were not the only ones interested in Italy: also by 800 BC, a number of the Greek city states had also established settlements in southern Italy and Sicily. These were not merely imperialist colonies: the outposts also served as a buffer from the increasing number of forays from the aggressive and powerful city of Carthage, situated on the North African coast in the country known today as Tunisia.

A Roman cavalry officer, from a sarcophagus found in Asia Minor (Turkey) circa 50 AD.

ROMULUS AND REMUS

According to Roman legend, the city of Rome was founded around the year 753 BC by the orphaned twin brothers Romulus and Remus, who were saved from death in their infancy by a she-wolf who had sheltered and suckled them.

Whatever the origins of the city, it is so that by the year 700 BC, the city had been firmly established on the seven hills around the Tiber River valley, and by the 6th Century BC, the city and surrounding areas were ruled by the Etruscans.

The city of Rome was at this stage ruled by kings elected by the people. The symbol of the elected king of Rome became known world wide an enduring symbol of power: an axe head bound together in a bundle of reeds, called a fasces.

The rationale behind the symbol was that each tribe was represented by one reed - by themselves they could be easily broken, but bound together they could be a powerful force.

Roman lictors carrying fasces - reeds bundled together with an ax head fastened in-between. The symbol of authority in ancient Rome, it derived its meaning from the fact that singly, reeds can be broken and bent, but bound together, they are strong. The fasces symbol was taken world wide as a symbol of authority, and can be found in much western architecture the world over. Benito Mussolini and the Italian Fascist Party took not only the emblem as their own, but also their name from the fasces.

The fasces symbol, which was used by the 20th Century Italian leader Benito Mussolini, can still be seen today reposing under the hands of the Abraham Lincoln Memorial in the capital of the United States of America, Washington D.C., and inside the American Congress house itself.

Advising the first Roman kings were the heads of all the leading families gathered together in a group called the senate.

This body remained in place, with varying powers, until the fall of the Roman Empire some 1,500 years later.

The senators and their families became the upper class of Rome, called the patricians, while the common people were known as the plebeians.

THE EARLY REPUBLIC (509 BC - 133 BC)

In the year 509 BC, a group of patricians led a rebellion against a particularly unpopular Etruscan king, threw him out and set up a Republic in Rome. This rebellion's most famous incident was a battle outside the gates of Rome when the legendary Roman soldier Horatio personally faced off the Etruscan king's army while the bridge to the city was destroyed, preventing the Etruscans from regaining control of the capital.

The power held by the former king was now passed on to two annually elected rulers, called consuls. Other cities within central and northern Italy formed an alliance and challenged the power of the new republic of Rome, leading to a Roman defeat at the Battle of Lake Regillus in 496 BC.

Three years later, in 493 BC, the Republic of Rome joined the alliance, and it became known as the Latin League and set about dislodging the last of the Etruscan strongholds.

Although originally not as advanced as the Etruscans, by 400 BC the Latini had adopted much of Etruscan culture and had in all respects surpassed their former masters, both militarily and culturally. The secret of their success - as indeed with the whole Roman Empire - was their astonishing ability to organize on a scale not seen since the days of the first Egyptians.

By 400 BC, the Latin League had successfully overthrown all the last vestiges of Etruscan rule, and from then on the Etruscan peoples were completely absorbed into the Latini, creating a Nordic/Alpine/Mediterranean mix which became characteristic of the early and middle Roman Empire, with Nordic elements tending to form the ruling class.

Rome was acknowledged by all the tribes making up the Latin alliance as the leading city, even though, as it later turned out, they were unhappy with the situation.

It was during this period of nation forming that the Romans wrote their first major legal code: in 450 BC, the Law of the Twelve Tables was laid down, which served as the basis for not only the entire Roman legal system, but also the basis of virtually all modern legal systems in the world today.

(In a mirror of the older Greek Spartan tradition, the Twelve Tables specifically called for the euthanasia death of any infant showing conspicuous deformities or retardation - an example of basic eugenics at work amongst these early Romans.)

CELTIC ATTACK - THE SACKING OF ROME IN 387 BC

However, the Romans faced another serious crisis. In 387 BC, Gauls, the descendants of Celtic tribesmen who had settled in France, launched an attack on Rome, and eventually sacked the city. They were only finally persuaded to leave by the Romans bribing them with gold.

The Gaulish invasion however showed a serious weakness in the ranks of the Latin League - the other components of the alliance had refused to help Rome against the Gauls.

This was not forgotten by the Romans, who, by 380 BC had not only rebuilt their city and had erected huge defensive walls around it, but had also started preparing a new and more powerful army than before.

In 338 BC, after entering into an alliance with certain smaller tribes around Rome, the Romans turned on their former allies in the Latin League and decisively defeated them, becoming by 280 BC, the dominant force in Italy.

GREEK WARS

As Roman power and influence grew, so it became ever more inevitable that a clash with the Greek settlements in southern Italy would follow. War did indeed break out as the Romans started occupying the southernmost points of Italy.

A Grecian king named Pyrrhus, from the city of Epirus in Northern Greece, was hired by one of the Grecian cities in southern Italy, Tarentum, to help ward off the Romans. Pyrrhus managed to inflict a defeat upon the Romans which temporarily stayed the latter's excursions.

An original bust of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, who came to Italy and Sicily with his army and elephants to help the Greek cities in those territories. Although gaining an initial victory, it was at such a cost to his forces that he was ultimately defeated. Ever since then, any hollow victory which ultimately leads to a defeat is known as a pyrrhic victory.

However, the cost of the victory - in terms of men and materials - was so great, that it exhausted the Greek expeditionary force, and by 270 BC, all of Italy had fallen to Rome, with the Greeks being unable to maintain the war against Rome. Ever since then, any empty victory - which ultimately leads to a long term defeat - has been called a Pyrrhic victory.

CARTHAGE - A THREAT TO ROME

With the elimination of Greek bases in Italy itself, only the city of Carthage on the North African coast served as a power which could seriously threaten further Roman expansion. Carthage had been founded around the year 800 BC by the mixed Mediterranean/Semitic Phoenicians, and had become an independent and powerful force in its own right.

Carthage had grown over the centuries, with a large Nordic infusion having taking place after the region's occupation by Alexander the Great, and by the time of the wars with Rome, Carthage was at its peak.

The Latin word for Phoenician was Punicus - from which the word Punic was to derive, hence the Roman wars against Carthage are called the Punic wars.

THE FIRST PUNIC WAR (264 - 241 BC)

In 264 BC, war broke out between Rome and Carthage over possession of the island of Sicily. After suffering initial reverses, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians, who were forced to sue for peace in 241 BC. In terms of the peace treaty, Rome administered Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, adding to the growing territorial possessions of the city republic.

The city of Carthage, situated on the present day Tunisian coast, was for many years Rome's greatest enemy. Originally established by the Phoenicians, the city's population received a massive infusion of Nordic blood when it fell under the control of the Macedonian Alexandrian empire. Its ruling classes became virtually exclusively Nordic, and the city was built up on a scale that rivaled even Rome itself. Below: The remains of the harbor of Carthage, as it was captured in a photograph in the early 1920s, and below that, a reconstruction of what the harbor looked like in its prime, based on archeological diggings and Carthaginian and Roman descriptions of the great city. When Rome finally overwhelmed Carthage, its soldiers razed the city to the ground and built a Roman city next to the ruins.

THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218 BC - 201 BC )

The Second Punic War is also known as Hannibal's war, named after the great Carthaginian general who, after a long epic campaign, very nearly routed the power of Rome. After having lost control of Sicily and other Mediterranean islands, Carthage sent an army to invade and occupy Spain between 237 BC and 219 BC. The original Whites and Celtic settlers in the region were no match for the battle experienced Carthaginians, and were overrun relatively quickly.

Then, starting in 218 BC, Hannibal led an army of about 50,000 men and a troop of 37 African elephants across southern France, through the Alps in northern Italy (all but one of his elephants survived the incredible journey) and attacked the Romans virtually continually for the next fifteen years up and down the length and breadth of Italy.

Hannibal had many victories, with the greatest being the battle of Cannae where he defeated a numerically superior Roman force. For a while it appeared as if the Romans had finally met their match - but a Roman general, Scipio, hit upon the idea of repaying Carthage in kind. He invaded North Africa, using the logic that if Hannibal could invade Italy and threaten Rome, the Romans could invade North Africa and threaten Carthage. The tactic worked, and Hannibal was forced to return to defend Carthage, leaving behind much of his army on the European mainland.

Rome was then able to invade Spain and drive out the Carthaginian armies. Hannibal was finally defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, and another peace treaty followed. According to the terms of this treaty, Carthage agreed to disarm, pay an indemnity to Rome and hand over their Spanish colonies to Roman rule.

Hannibal himself was never forgiven by the Romans, who pursued him right into Asia Minor (Turkey) where he committed suicide in 182 BC.

A silver coin struck at Carthage around the year 220 BC, showing the Nordic face of Hannibal, that city's greatest warrior. Founded by the Phoenicians, the city of Carthage had received a major Nordic sub-racial input when it was occupied and colonized by Nordic Macedonians under Alexander the Great. It was from a long line of Nordic Carthaginian nobles that Hannibal was born.

A bronze bust of the Roman general, Publius Scipio, who finally defeated Hannibal at the battle of Zama in 202 BC. The Romans called their new colony "Africa" - and in this way the White Romans gave Africa (and Africans) the name by which that continent and its people are known today.

Hannibal's troops crossing the Rhone River on their way to attack northern Italy. Only one elephant actually survived the crossing of the Alps.

GREECE OCCUPIED - 146 BC

The defeat of Carthage left the Romans free to assert their authority in the east. The Macedonians, who had helped Hannibal, were first to be punished for this deed by the Romans.

The Legions of Rome invaded Macedonia in 200 BC, defeating

the Macedonian army in 197 BC. The Greek mainland then came under Roman protection,

although many city states were allowed self rule.

However, continuous turmoil and infighting between many of these cities eventually

compelled Rome to directly occupy the whole region, an operation which was completed by

146 BC (in that year Roman legions destroyed the Greek city of Corinth.)

For 60 years after 146 BC, Greece was almost completely administered by Rome, although some cities, such as Athens and Sparta, retained their free status.

In 88 BC, Mithridates, the king of Pontus, invaded Roman held territories from the east - many cities of Greece supported the Asian monarch with the belief that they would regain their independence.

A Roman army forced Mithridates out of Greece and crushed the rebellion, sacking Athens in 86 BC, and Thebes a year later. Roman punishment of all the rebellious cities was heavy, and the campaigns fought on Greek soil left central Greece in ruins. In 22 BC, the Greek city-states were separated from Macedonia and the Romans made these city states into one province called Achaea.

During the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (117 - 138AD), many of Athens' famous buildings were restored out of the ruins. The continuing Roman restoration work was however interrupted by an invasion of Goths, who in 267 AD and 268 AD, overran Greece, captured Athens, and laid waste the cities of Argos, Corinth, and Sparta.

From the 6th to the 8th centuries, Slavonic tribes from the north migrated into the peninsula, occupying Illyria and Thrace.

After the Goths left, the Grecian peninsula, thoroughly ravaged by centuries of warfare and racial mixing, settled down to obscurity as a province under the Eastern Roman Empire of Byzantium.

EGYPT

Rome had by this time succeeded in establishing itself as the dominant new power in the Mediterranean, and in 168 BC, Egypt (then still under Macedonian Ptolemaic rule) formerly allied itself to Rome. This meant that by 168 BC, most of the Mediterranean - from Spain right around the Mediterranean coast through Greece, parts of Turkey, Egypt and the north African coast up to Tunisia, was either under direct Roman rule or allied to Rome.

THE THIRD PUNIC WAR (146 BC)

The enmity between Carthage and Rome was so deep that it could not however be buried with a mere treaty, and in 146 BC, war between the two powers broke out once again. By this time, however, Roman power was vast - Carthage itself was besieged and destroyed.

Angered at being constantly threatened by the same enemy repeatedly, this time Rome wrote no treaty with Carthage. To ensure that the Carthaginians never threatened them again, the Romans killed or enslaved the population of Carthage, physically destroyed the city and ploughed over the ruins, putting salt into the earth so that nothing would grow there again.

At the end of the Third Punic War, the Romans physically occupied what is today known as Tunisia and refounded a new city of Carthage - a Roman one. They called it the province of "Africa" - a name which later was used to refer to the entire continent. In this same manner, Roman conquests in the east led to the creation of the Roman province of 'Asia" - once again a Roman name became the name of an entire continent.

THE LATE REPUBLIC (133 - 30 BC )

In 133 BC, the ruler of an independent state in central Asia Minor (Turkey), one Pergamum, died. When his will was read, he had left his country to Rome. This somewhat bizarre wish - which was duly carried out - served as a springboard for the later Roman occupation of the rest of Asia Minor and the Near East. The period from 133 BC to 30 BC is known as the late Republic, during which Rome itself was to experience civil strife not seen since the days of the Latini insurrection against the Etruscans. In addition to this, Rome also engaged in a number of foreign wars.

SLAVES - THE SEEDS OF ROME'S DECLINE

From the very earliest times the Romans had also been importing slaves into their homeland - a policy which was to grow into a major commercial activity in Rome itself - but also ultimately to lead to Rome being filled with all manner of people who bore no resemblance to the Romans themselves. Slaves from the Far East, Africa and the Semitic speaking world filled the slave houses of Rome in their hundreds of thousands.

Eventually such large numbers created the possibility of open rebellion, with the most famous being the slave rising led by Spartacus in 73 BC, which had to be suppressed by force of arms with a full Roman army.

CIVIL WAR - STRIFE BETWEEN PATRICIANS AND PLEBIANS

Internally, Rome had become increasingly divided between the patricians and the plebeians, especially with regard to land distribution. Some patricians realized the need for reform, the most famous being Tiberius Gracchus, who was elected to the post of tribune (a modern equivalent would be a prime minister) in 133 BC. The reforms Gracchus implemented earned him the hatred of the wealthy classes, and in 134 BC, he was assassinated.

His work was however taken up by his brother, Gaius Gracchus, who was elected tribune in 123 BC. Again initiating far reaching social reforms, Gaius succeeded only in establishing a form of social welfare system which did not work properly and virtually bankrupted the state, serving only to stir up the hatred of the upper classes in a manner not seen even against Tiberius Gracchus.

In 121 BC, after a particularly severe outbreak of civil violence in which several thousand of his supporters were killed, Gaius Gracchus committed suicide. The deaths of the Gracchus brothers was to herald all out civil war in Rome.

By the year 100 BC, a number of able Roman generals had risen to prominence, emerging from the virtually constant need to subdue and to hold on to the numerous Roman colonies scattered around the Mediterranean coast. Each of these generals was in command of their own army, and although they theoretically were supposed to serve the Roman state, in reality they operated as virtual private armies working in the interests of their generals.

SULLA - DE FACTO RULER OF ROME

After physically clashing with some of the other armies, General Cornelius Sulla emerged as the strongest leader and became the de facto ruler of Rome. Remarkably enough, after introducing a number of reforms (including extending the powers of the senate) Sulla resigned voluntarily from the affairs of state.

POMPEY AND CAESAR CLASH

By this time however, two other generals had also emerged, each with their own armies: Pompey and Julius Caesar.

Pompey had led Roman legions far and wide, in Italy, Africa, Spain, Asia Minor and even as far as the Euphrates River valley. He had also been instrumental in helping to suppress the famous slave uprising led by Sparticus in 73 BC.

Julius Caesar had conquered Gaul (France) and some of the Germanic tribes (descendants of the original Celts and far off cousins of the original Latini) as far as the Rhine River. He had even landed an invasion force in Britain between the years 58 - 51 BC.

As Caesar's name, fame and influence spread, Pompey and others in Rome realized the threat and ordered him to disband his powerful army and return to Rome. Caesar refused to do so, and instead marched on Rome itself from his base in France.

Caesar crossed the Rubicon river in 49 BC, irrevocably committing himself to war with Pompey (the Rubicon marked the official boundary of Rome, and hence once crossed, the declaration of war was taken for granted). Within a short while, Caesar crushed all opposition and formally established himself as ruler.

Left to right: Julius Caesar, most famous of Romans; center: Brutus, one of Caesar's assassins; and left: Augustus, Caesar's successor. All original Roman sculptures.

CAESAR'S EXPLOITS

Although the most famous of the Romans, Caesar in fact only ruled for five years, from 49 BC to 44 BC. He was an outstanding writer and orator, and instituted far reaching reforms, from altering the make-up of the senate to the institution of a public works program. He also introduced the Solar calendar (based on Egyptian knowledge - which in Rome became known as the Julian calendar) which, with minor alterations, is the same one the Western world uses to this day.

Caesar took as his mistress the Macedonian Ptolemaic queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, in what was most likely a strategic alliance on both their parts.

In 44 BC, Caesar was however assassinated on the steps of the senate in Rome by a group opposed to his almost royal control of the affairs of state. Caesar did indeed consider his powers to be hereditary, and left a will in which he named his 18 year old nephew, Octavian, as his heir.

OCTAVIAN AUGUSTUS - CAESAR'S HEIR

After suppressing and exterminating much of the opposition (including the renowned orator and senator, Cicero) Octavian and one of Caesar's colleagues, Mark Anthony, ruled with complete autocratic powers for a decade.

Mark Anthony however married Cleopatra, Caesar's former

mistress, giving her Roman territories as wedding gifts. Octavian took this act as an

opportunity to incite Rome against Mark Anthony and the long standing partnership between

Mark Anthony and Octavian degenerated into civil war.

Both Octavian and Mark Anthony had large fleets at their disposal, and they finally met in

battle in 31 BC, at Actium in Greece. Mark Anthony was defeated and committed suicide, as

did his wife the following year when the city of Alexandria was captured by Roman forces.

PAX ROMANA 30 BC - 235 AD

At the end of the century of civil strife (133 BC - 30 BC), Rome was finally united under one ruler. Thereafter ensued what became known as the Pax Romana, the Peace of Rome, which lasted for well on 200 years, from 30 BC to 235 AD.

This time was also to mark the racial undoing of the Empire, caused by the long term effects of the inclusion of foreign lands and peoples under the aegis of the Roman Empire, and significantly by the bypassing of a law set down by the first Romans prohibiting mixed marriages outside of the Roman circle of citizenship.

Upon Octavian's' victorious return to Rome in 29 BC, the senate conferred upon him the title of honorable (Augustus) or August, a name by which he became known thereafter. Octavian Augustus held no official government position in Rome after 23 BC, but still was almost absolute ruler of Rome until his death in 14 AD, through the Roman army, of which he remained supreme leader, or imperator (from which the word emperor came).

The Pax Romana is also known as the principate - as political power was divided between the senate and the "principes", the leading person of society (the "first amongst equals", as Octavian described his own position.)

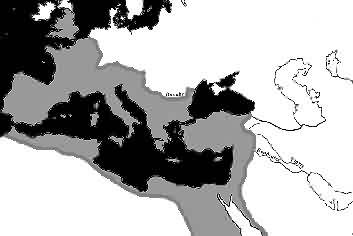

The Pax Romana - the extent of the Roman Empire at the time of Octavian Augustus, 14 AD.

During his long reign (44 years in all), Octavian Augustus established a stable and efficient public service, an equitable taxation policy and consolidated the Roman Empire's borders.

Under his command the borders of the Empire moved up the Danube River and into Germany as far as the Rhine - but he suffered a dramatic reverse when the Germans inflicted a massive defeat upon the Roman armies in 9 AD at the Battle of Detmold.

In the Near East, Sulla's army had campaigned against the (by now racially mixed) Parthian empire as early as 92 BC, but it was only the emperor Trajan who managed to finally subdue the Parthians - although he quickly handed their lands back to them in what was claimed to be an act of conciliation.

THE JULIO-CLAUDIAN DYNASTY

Upon Octavian Augustus' death, he was followed by four descendants of his family, called the Julio-Claudian family.

The first two, Tiberius and Claudius, were just and

efficient, and it was during Claudius' reign that the occupation of Britain, began by

Julius Caesar some 100 years earlier, was completed (in 43 AD).

The third Julio-Claudian emperor was the famous Caligula, who is reputed to have gone

insane, once allegedly making a favorite horse into an ambassador.

The fourth Julio-Claudian emperor was the equally famous Nero, best known for his persecution of the Christians by throwing them to the lions. The Christians were at that stage still a tiny cult, one amongst many flourishing under the Pax Romana. The Julio-Claudian line came to an end in 68 AD with Nero's suicide, with Rome itself suffering severe damage in a big fire in 64 AD.

THE FLAVIAN DYNASTY

A brief power struggle erupted on Nero's death, and Flavius Vespasianus (also known as Vespian) assumed power in 69 AD. He restarted orderly government and founded the Flavian dynasty, which lasted until 96 AD. The still standing Colosseum in Rome was built by the order of Vespian.

Titus was Vespian's son, who ruled from 79 AD to 81 AD. Titus is best remembered for his military exploit of capturing Jerusalem in AD 70, nine years before he became emperor. By the time of the last Flavian emperor, most Romans had accepted that the Imperator, or Emperor, was the real ruler of Rome.

NERVA AND NONWHITES IN THE SENATE

Following the Flavian line came the Antonines - or the "five good emperors", who ruled from 96 AD to 180 AD. The first of these was the emperor Nerva, who ruled from 96 AD to 98 AD. Nerva is of importance because he established the rules of secession - before he died he adopted a promising individual (who would thereafter be called a Caesar). This individual was trained to take over the position of Emperor when the time came. This system set the standard for many years to come.

Nerva was also the first emperor to allow members of the Roman senate to be chosen from all over the Empire - which at that stage was still vast, extending into territories which many centuries earlier had last seen a White majority population.

Nerva's rule marks the first appearance of non-Romans - Nonwhites - in the senate, and hence the government, of Imperial Rome.

From then on increasing numbers of non Romans began to feature in the senate, until by the end of the Second Century AD, senators of pure Roman descent were in the minority in the senate.

DISSOLUTION OF THE ROMAN PEOPLE

The next emperor was Trajan, who ruled from 98 AD to 117 AD. Under Trajan, the empire reached its peak in terms of territorial expansion, but by this time huge numbers of racially foreign peoples had begun to fill not only virtually all of the non continental European Roman colonies, but had started to appear in significant numbers in Rome itself.

The next emperor, Hadrian (117 - 138AD), built the famous Hadrian's wall of stone across the North of England to keep the remnants of the Scottish Celts out of Roman England.

This was part of an attempt by Hadrian to reduce the size of the empire - possibly he saw the process of disintegration at work, and he ordered many territories in the eastern parts of the empire to be given up. Under his rule, large slices of the eastern territories, except for Dracia (modern Rumania) were effectively abandoned by the Roman Empire. If this was an attempt to stem the flood of foreigners pouring into the southern parts of the empire, it was a futile one.

ATTEMPTS TO INCREASE THE WHITE ROMAN POPULATION FAILED

An overt attempt to preserve the Roman bloodline had in fact been made by Octavian Augustus. He issued several decrees prescribing heavy penalties for celibacy or for marriage with slaves or the descendants of slaves. Another Octavian law was that all Romans between the ages of 25 and 60 must be married - and hopefully produce children.

Finally in the year 9 AD, Octavian announced tax concessions for Roman families with three or more children. Unmarried persons were barred from public games and could not receive inheritances, while childless married people could only receive half any inheritance due to them. All these measures failed during Octavian's own lifetime.

As early as 131 BC, the Roman Censor, Melletus, had called for a law compelling Roman citizens to marry - Caesar, Augustus, Nero and Trajan all offered prizes for Roman citizens having more than four children.

ROMAN IMPERIAL POLICY ENCOURAGED THE GROWTH OF NON-ROMAN PEOPLES

In continental Europe, the Pax Romana saw the benefits of Roman society bear fruit. The population increased and the Roman penchant for organization was swiftly taken up by the European peasantry in their regions. This process was enhanced by the Roman system of government, which relied on a few Roman administrators arriving in a region, and then getting locals to help with the administration and running of the territory, in return for offices of state.

In this way the Romans "Romanized" many of the subject territories: while this did not affect the racial balance in Gaul and other parts of western and eastern Europe (central Europe or Germany remained forever out of Rome's reach), it had dramatic effects in the regions to the east and south which were majority occupied by Nonwhite peoples. This policy was also applied in the other reaches of the Roman Empire - with disastrous consequences for Rome in the Mediterranean territories of North Africa, Egypt and the Near and Middle East.

In these latter territories huge numbers of the by then racially mixed populations (consisting of White, Semitic, Arabic and Mongol mixtures) drew the benefits of Roman civilization for as long as the Romans themselves existed. This meant a dramatic increase in the population due to increased living standards, and so the Romans helped to engineer the Nonwhite racial flood that would eventually overwhelm them from the south.

It is interesting to note that the original Indo-European descended Romans viewed anyone who was dark with suspicion. The Roman proverb "hic niger es, hunc tu, Romane, caveto" (He is black, beware of him, Roman) is recorded by Horace as being a common saying amongst Romans of the time. (Sat., i. 4, 85).

This is not to say that the Romans of the Late Republic or of the Pax Romana resisted the physical integration process. On the contrary, they seemed to have welcomed it as an essential part of Empire building and as a means to keep subdued populations under control.

It is unlikely though that they could have foreseen the long term consequences it would create - when the last of the true Romans were bred out in the vast reaches of the Empire, so did the original spark which had created the Empire in the first place.

Hence there are today only Roman ruins in Africa, the Near and Middle East, and indeed even in Rome today - silent monuments to a people long gone.

GERMAN RESISTANCE

That the Romans never managed to penetrate into central Europe past the Rhine river (they were halted by Germanic tribes by the year 9 AD) created a physical division in the White peoples of North Western Europe. At the time, one section (Gaul and Britain) fell completely under the sway of Rome - and the other (the German tribes) remained Rome's implacable enemies, fighting the Empire off at every opportunity which arose.

Ironically, these Germanic tribes (or barbarians as the Romans liked to call them) were originally far off Celtic cousins of the Latini - and it was these barbarians who were to finally overrun Rome itself when that city had managed to breed its true Romans down to an insignificant minority, causing the great Imperial flame to flicker and die at last.

An exquisitely executed relief on the Antonie Column in Rome, of legionnaires on the march. The Romans were able to overwhelm most of the known world through their staggering organizational abilities.

EXTENT OF EMPIRE PROVES ITS UNDOING

At its height the Roman Empire stretched from England to the Rhine, from Spain to Asia Minor, and from North Africa to the Tigris/Euphrates rivers. The vast numbers of peoples and races drawn into the Empire's influence does not need to be exaggerated. Roman coins found in India and Scandinavia indicate the extent to which Romans traveled, as traders or soldiers.

The Romans may have believed that the integration of foreigners into the Roman system of government and into Rome itself was the way to create an Empire. The reality is however that non-homogeneous societies are the least cohesive, while homogeneous societies are the most cohesive.

So it was that the ever increasing number of foreigners within the empire made it all the more difficult to hold together. Internal dissension, political problems and social ills were often compounded by brutal or incompetent emperors.

Finally, by 192 AD, the throne was actually auctioned by the Emperor's own private guard (the Praetorian Guard, founded by Octavian Augustus) after a particularly ineffectual emperor had been murdered after just three months in the office.

The lucky winner of the auction did not last very long himself - he was in turn deposed by an emperor effectively chosen by the largest part of the army: one Septimus Servus.

ROME'S FATE SEALED - CARACALLA AND THE EDICT OF 212 AD

Servus himself was unremarkable, but his son, Caracalla, who ruled from 211 AD to 217 AD, was the Roman emperor who finally opened the racial floodgates on the Roman Empire and sealed its fate.

In 212 AD, in an apparent attempt to broaden the Roman tax base, Caracalla passed an edict giving all free males within the Empire citizenship of Rome.

This proclamation, which effectively turned centuries of Roman Law on its head (previously Roman law had always sought to prevent Roman citizenship passing to those outside of Rome), had effects far greater than just broadening the taxation base.

Early Roman law had made provisions for the maintenance of racial homogeneity amongst its citizens, by stipulating that persons could only be citizens of Rome if both their parents were Roman citizens themselves.

Roman citizens who married non-Roman citizens could not claim Roman citizenship for their children. This was of course a very direct way of biologically excluding all foreign nationals from Roman citizenship.

As however the Roman Empire expanded, so the definition of citizenship became broader and broader, till finally with Caracalla's edict, all free men, no matter what their racial or national origin, qualified for Roman citizenship. The last hold preventing the dilution of Roman blood had been abandoned.

Left: The Emperor Caracalla (ruled 211 - 217 AD) who extended Roman citizenship to all free peoples within the boundaries of the Roman Empire, and thereby gave legal sanction to the final dissolution of the Roman people. Born in Gaul of a Roman father and a Syrian mother, his own potentially dubious ancestry, must have also played a role in his decision to extend Roman citizenship. His features contrast, for example, with those of M Vipsanius Agrippa, a Roman general under Augustus (right), who lived some 200 years prior to Caracalla.

UNIVERSALITY LINKED TO THE RISE OF CHRISTIANITY

While the early Romans therefore placed great emphasis on maintaining their racial homogeneity, by the first century AD, the idea of universality had become an undercurrent: it was to become the main train of thought by the second century AD, and is directly linked to the rise of Christianity, which has the world-view of the universality of man as its underlying creed.

By the time of Caracalla's edict, the sheer size of the empire and the fact that it had already included so many racially alien elements within its borders, had made a large amount of racial mixing inevitable - Caracalla's edict gave legal support to this process.

Interracial marriages and mixed race children became more and more common after this, and slowly but surely, Rome and the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean lost its majority White leadership core.

Thus the fate which had befallen all the other great civilizations, namely the disappearance of the people who created those civilizations through physical integration, crept up on Rome itself.

Although this change in racial demographics was not as marked in Rome itself as in the easternmost outreaches of the Empire, it was however dramatic enough to change the very nature of the civilization.

Foreigners from all over the already mixed race Middle East poured into Rome, attracted by its wealth and status. Being granted citizenship, these foreigners were steadily absorbed into the Roman population, to the point where today only a very few Italians can still today claim pure Roman descent.

Huge swathes of the southern part of Italy and Sicily are today clearly Nonwhite, being mainly a mixture of Arabic and White, while in scattered places there are flashes of the original population, light skins, light eyes or light hair - as there are right across the Mediterranean and as far afield as Iran or India.

ROMAN FALL MIRRORS THAT OF SUMERIA, EGYPT

The path followed by Rome mirrored that followed by Sumeria, the Near East, Egypt and Greece. All these civilizations remained intact as long as the society which created them remained homogeneous.

As soon as these societies lost their homogeneity and became multi-racial, the very nature of the societies changed and the original civilizations disappeared. Rome would prove to be no exception to this rule.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.