MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 29 : IRELAND - 500 YEARS OF CIVIL WAR

It has been said that Ireland's greatest export has been people - this is most certainly true. In Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, North and South America - and in Europe itself - the Irish presence has been felt, influencing the racial make-up of three major continents.

Ireland is also of importance for it remained the site of one of the longest running White civil wars in history, with the White Irish fighting with the White English on and off for over 500 years. This, combined with its massive emigration history, makes Ireland more than worthy of study.

ANCIENT IRELAND - NAME DERIVED FROM "ARYAN"

The island of Ireland was, like Britain, initially inhabited by tribes of Old Europeans and Proto-Nordics. These people were however either overwhelmed or assimilated by the first Indo-European invaders to reach the island in the first millennium BC. The Celts settled the island in large enough numbers to feature in the writings of the Classical Greeks (the first reference to Ireland is made under the name the "Irene" in a Greek poem dating to 450 BC and by the names of Hibernia and Juverna by various classical writers).

Great underground megalith tombs and above ground megalith structures can still be found in abundance in Ireland, evidence of a flourishing Neolithic society, comparable with anything in the rest of Europe at the time.

Newgrange barrow mound in Country Meath, Ireland. Constructed in approximately 2500 BC, it is one of the finest passage graves in western Europe, almost 100 meters in diameter and 10 meters in height. It was so constructed that at noon, the sun shines through a specially made slot just above the entrance, directing rays into the furthest recesses of the tomb. The splendid construction is a tribute to the early White builders of Neolithic Ireland.

According to Irish folklore, the Celts established four major kingdoms, known in the Gaelic language as Nemedians, Fomorians, Firbolgs, and Tuatha DU Danann.

The Indo-European origin of Ireland is however most clearly represented in the traditional name for the whole island which finally became its official name: Eire, derived from the same root word as Aryan.

One powerful Celtic tribe, the Scots, left Ireland for reasons unknown. They settled in the far north of Britain and eventually gave their name to Scotland.

ST. PATRICK

Other Irish Celts continued to raid and harass Roman occupied Britain, with advance parties even reaching the coast of France to search for booty. During the reign of the Celtic king MacNeill (428 to 463) a Romanized English missionary, Patrick, entered Ireland in an attempt to convert the pagan Celtic natives away from their traditional Indo-European religions.

Patrick was not, as is commonly believed, completely successful. Nonetheless he did enough to ensure that Christianity - or Catholicism - became entrenched enough to become the dominant and virtually the only religion a century after his death in 461. In the 6th Century, extensive monasteries were founded in Ireland and it was from these centers that missionaries were sent to all over the known world, including back into England when that land fell under pagan Germanic rule.

VIKING RAIDS AND SETTLEMENTS

During the 8th Century, Ireland was, along with almost all of France and Britain, thrown into confusion and panic by the Viking invasions. The Vikings were particularly fond of raiding Ireland, finding the Celtic tribes generally too busy fighting with each other to offer organized resistance. The Vikings liked Ireland so much that they soon established permanent settlements on its east coast, raiding ever deeper into the interior of the island. Finally the Viking raids were brought to an end when the Irish King, Brian Boru, decisively defeated a large Viking force at the Battle of Clontarf, near Dublin, in 1014.

Nonetheless the establishment of the Viking settlements created the first major population shift in Ireland since the Celtic invasions: a fresh wave of Indo-European Nordic blood was settled in Ireland, further adding to the already overwhelming Nordic/Old European sub-racial characteristics of the Irish.

THE ANGLO-NORMAN OCCUPATION - HENRY II INVADES

The first English invasion of Ireland took place under King Henry II, who claimed to have received official authorization for the conquest of the island from the Pope.

The authenticity of this order has long been called into question, but the upshot was that by 1169, an English army had entered Ireland in support of a deposed local Irish king, Dermot MacMurrough of the Irish kingdom of Leinster, who had asked the English for help in subduing his rebellious subjects.

In 1172, Henry gave permission to Norman lords (at this stage Normandy and England were united kingdoms) to settle portions of Ireland. In this way yet more Viking descendants (the Normans had themselves originally been Viking settlers in France) settled in Ireland.

Quickly they struck up a rapport with their distant sub-racial cousins already in Ireland, and soon alliances between the Normans and the Irish were formed to the detriment of the English.

English power was further challenged by the 1314 invasion of Ireland by Edward Bruce, the younger brother of Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland, who attempted to throw the English out of the ancient home of the Scots. The enterprise failed, but the English population in Ireland was decimated.

The English King Henry II, who first started the English intervention in Ireland with an invasion of that country in 1169. Claiming to have received sanction from the Pope for the invasion - a highly dubious claim - Henry then allowed Norman lords to settle in the land, creating a festering political sore which has plagued the English for just under 1,000 years.

NORMANS FORBIDDEN FROM ALLIANCES WITH THE IRISH

The increasing integration of the Normans into the native Irish was recognized by the English as meaning eventual trouble. The Anglo-Irish Parliament passed in 1366 the Statute of Kilkenny, which punished all those who "followed the custom of, or allied themselves with" the native Irish. Such action was punishable by excommunication and heavy fines.

This law was useless: the process had advanced so far that even though a new English army invaded Ireland in the late 14th Century, the Irish were fast becoming coalesced as a nation in their own right.

This was emphasized during the English War of the Roses, when English settlements in Ireland decreased to a small coastal strip around Dublin. This strip became known as the English Pale - and from there the English saying that if something is "beyond the pale" it is unacceptable - a good indication of how the English settlers viewed the native Irish.

ENGLISH ASCENDANCY

In 1494, the English soldier and diplomat, Sir Edward Poynings, was appointed by the English monarch to look after and extend English interests in Ireland.

Acting on royal authority, Poynings revived the Anglo-Irish Parliament and the Statute of Kilkenny, which compelled the English and Irish to live apart and prohibited Irish law and customs in regions inhabited for the largest part by English settlers.

All state offices were filled with appointments made by the English king and English law was declared to be valid for large parts of the island.

Finally, Poynings introduced the act known as the Poynings Law, which made any law passed by the Irish parliament invalid until the English king had given his assent.

THE REFORMATION

The English King Henry VIII had overthrown the Catholic Church in England - now he attempted to extend this to Ireland.

The monasteries were disbanded and a great many destroyed - much of the riches they had hoarded was distributed amongst Irish nobles, and their support for the English king was thereby quite literally bought.

Henry also wisely extended the right of home rule to the Irish. The result was a period of relative peace, and in 1541, the Irish parliament declared him King of Ireland in recognition of this achievement.

INCREASED ENGLISH SETTLEMENT

Although the English Queen Mary was Catholic (and she tried hard to contain the Anglicans in England) she was the first monarch to begin the large scale colonization of Ireland by English settlers. At first conciliatory towards the Irish, a rebellion in Ulster led by the Irish chieftain of that region, Shane O'Neill, drew "Bloody Mary" to more drastic measures: an act was passed dividing all Ireland into counties. The rulers of these counties were invested with military powers, which they used with cruelty against the native Irish.

SEEDS OF HATRED SOWN

The reconversion of England back to Anglicanism under Queen Elizabeth I caused a number of Irish Catholic rebellions - after one unsuccessful uprising, an English army was defeated at the Battle of Blackwater in 1602.

During these wars, the English aroused great hatred towards themselves amongst the Irish. Villages, crops and cattle were destroyed to try and root out native resistance - thousands of Irish were executed out of hand. When English soldiers fell into Irish hands, they could therefore expect no mercy and many were tortured in turn. The greater part of Munster and Ulster was destroyed, and more Irish died from the resulting famine than in the war itself.

The extension of the Anglican Church into Ireland was also associated with English political control, and by default the vast majority of Irish were reconfirmed in their support for the Catholic Church - religion became a way of demonstrating political opinion.

ENGLISH LAW AND THE SIX COUNTIES

During the reign of the King James I, English law was declared the sole law of the entire Ireland - some 100 Irish chieftains were forced to flee Ireland and went to Rome where they sought the protection of the Pope in 1607.

The lands of these chieftains - six counties in the north - was confiscated: they were to become famous as the six counties of Northern Ireland. Increasing numbers of English - and Scottish - settlers were encouraged to settle in these confiscated counties.

IRISH REBELLION - 30,000 ENGLISH SLAUGHTERED

A local Irish chieftain, Rory O'More, then hatched a rebellion in 1641 to seize Dublin - the castle in that town being the main center of English rule in Ireland - and drive the English out. The rebellion succeeded: the Irish took a terrible revenge upon the English settlers in Dublin, killing, by some estimates, up to 30,000, with only Scots being spared. The rebels were soon joined by the Catholic Irish nobles in the pale - together they elected a new Irish parliament to rule the island. The co-operation between the rebels and the nobles of the pale came to an end in 1647 when the English promised the pale inhabitants that the Catholic Church would be allowed to dominate in Ireland if they assisted in the English reconquest of Ireland.

CROMWELL INVADES

In 1649, the English Puritan (extremist Protestant) leader Oliver Cromwell invaded Dublin. With a 10,000 strong army, he retook Dublin castle, executing all 2,000 rebels who surrendered. After defeating one more rebel army, a great part of the best land of Munster, Leinster, and Ulster was confiscated and divided among the extremist Protestant soldiers of the English army.

Catholics were actively forbidden from holding any important offices of state and made completely subject to the English invaders. This policy was however reversed by the English King James II, who had already alarmed the Protestant parliament in London with his slow attempts to resuscitate the Catholic Church in that land. Under James II, Catholics were once again promoted to high offices in Ireland.

The result was that when, in 1688, James fled England after the arrival of William of Orange, he found the Catholic population of Ireland ready to stand by him.

Protestant settlers in Ireland were once again driven from their homes and took refuge in the heavily defended Protestant towns of Enniskillen and Londonderry, which James attempted to capture with his new Irish Catholic army. James' army did not however have any artillery and could not break the city walls: Londonderry was relieved by sea.

James then called together the Irish parliament and restored all the lands confiscated since 1641. In 1689, the new English King, William of Orange, followed James into Ireland, and at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, the Irish army was defeated and James fled.

William failed however to capture the city of Limerick and when his artillery was destroyed outside the city, he was forced to retreat. The next year an English army however defeated an Irish army at the town of Aughrom and Limerick was forced to surrender.

THE PENAL LAWS - DESTRUCTION OF IRISH ECONOMY

The English Parliament then exacted severe punishment on the Irish - the Penal Laws restricted the rights of the Catholic Church in Ireland. Laws passed in 1665 and 1680, effectively killed Irish commerce and industries by banning the export of Irish cattle, milk, butter, and cheese.

In 1699 the export of Irish woolen goods was forbidden. These measures effectively caused Ireland to be placed under an economic blockade, resulting in steady economic decline and serious poverty.

The most important effect of these laws were however to create the first wave of Ireland's largest export: people. Impoverished under the English blockade, hundreds of thousands of Irish started leaving the island, some going to France, but most going to North America in search of freedom from direct English rule.

The emigration of the Irish to almost all parts of the world would in time become the dominating foreign affair of Ireland, with possibly as many as a million all told, leaving the land because of the dire conditions created by the Penal Laws and their aftermath.

CONTINUED DISSENT - CATHOLICS DENIED THE VOTE

The American Revolution not only created admiration in Ireland, but also awakened the English to the possibility of another rebellion in Ireland.

Subsequently in 1778, the Irish parliament, which only had Protestants in it (Catholics were not allowed to vote) passed the Relief Act, removing some of the most oppressive anti-Catholic measures. The English parliament then followed suit and repealed the Poynings Law and much of the other anti-Catholic legislation.

The outbreak of the French revolution sparked off a rebellion in Ireland - in 1798 the Society of United Irishmen led a rebellion which nearly captured Dublin. They were however too lightly armed to defeat the regular Protestant army, and the landing of a French force of 1,000 men in Ireland came too late to save the rebels.

By this time however, the stage had been set for a long lasting and bloody duel between the Irish and the English - a conflict which would last to the 21st Century.

UNION BETWEEN IRELAND AND GREAT BRITAIN

The British Prime Minister William Pitt, the Younger, then enacted the union of Great Britain and Ireland in an attempt to strike a balance between the continual Roman Catholic Irish rebellions and the anti-Catholic Protestant minority in Ireland.

The official union of Great Britain and Ireland was officially proclaimed on 1 January 1801. In exactly 121 years it would be dissolved. The union was two years old when the first rebellion broke out: in 1803, Robert Emmert led a brief and unsuccessful uprising which was easily suppressed.

In 1823, the Catholic Association was founded, which demanded, and finally obtained, complete Roman Catholic emancipation in Ireland. In 1828, Roman Catholics were permitted to hold local office, and in 1829, they were allowed to sit in Parliament for the first time.

These reforms came despite a new war over the practice of the compulsory payment of tithes by all inhabitants of Ireland- irrespective of whether they were Catholic or Protestant - which were paid to maintain the Anglican Church.

Both Catholics and Protestants fought each other with great cruelty during the Tithe Wars, as they were called, which ended with the conversion of the payment of the tithe tax into rent charges - further discontent led to the almost constant brewing of plots and rebellious societies.

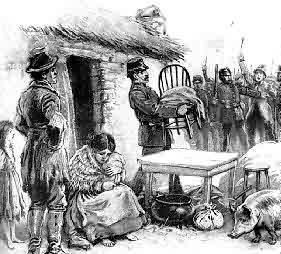

Sowing the seeds of hatred - English police evict Irish peasants during the 1880s from their homes for not being able to pay their rent. Every English law was seen, sometimes justifiably, as an affront to Irish nationalism. Such moves always drew a counter reaction from the Irish nationalists, and this, combined with the clear Catholic/Protestant division which had crept in between the English settlers in the north of that island, and the native Irish, served to make a lethal brew which was still not fully resolved at the end of the 20th Century.

POTATO FAMINE - POPULATION DECLINES BY 2 MILLION

During the five years from 1845 to 1850, the potato crop in Ireland failed - it led to a disastrous famine which caused a second massive wave of Irish immigrants, again mainly to America. Through emigration and death from famine, the Irish population declined by as much as 2 millions during this five year period.

REBELLION BREWS

The Irish nationalists did not however accept the Union. In 1867, another revolt broke out in Dublin and Kerry which had to be suppressed by British force of arms.

Soon it became as usual for British soldiers to serve in Ireland as in any part of the Empire - the sheer necessity for occupying troops meant that the land was a colony and nothing more.

In 1902, the Irish political leader and journalist Arthur Griffiths founded a group that later became the nucleus of Sinn Fein, which became in that time the most important Irish nationalist force and which ultimately led to Irish Independence.

THE EASTER REBELLION

Sinn Fein organized a military wing, as did many main Protestant groups, and by 1914 civil war seemed inevitable. The outbreak of the First World War however overshadowed events, most importantly leading the British parliament to set aside a bill allowing for Irish home rule.

The suspending of the home rule bill saw three small nationalist groups, the Citizen Army, an illegal force of Dublin citizens, the Irish Volunteers, a national defense body, and the Sinn Fein, draw together with their military wings and organize what became known as the Easter Uprising.

At midday on 24 April 1916, about 2000 Irish nationalists seized control of the Dublin Post Office and other strategic points in the city. The leaders of the rebellion then proclaimed Irish independence, and by 25 April, they controlled most of Dublin city.

The British launched a counter offensive on 26 April, and martial law was proclaimed throughout Ireland.

Bitter street fighting took place in Dublin, and the better armed British forces slowly dislodged the Irish nationalists from their positions one by one.

By the morning of 29 April, the post office building, site of the rebel headquarters, was under attack by such overwhelming numbers that the last rebels surrendered that afternoon. About 440 British troops were killed in the uprising, and at least a similar number of Irishmen were killed. Fifteen of the rebels were executed. The American born Irishman, Eamon de Valera, leader of Sinn Fein, was also sentenced to death. His sentence was however commuted to life imprisonment, and then he was granted amnesty the next year.

The remains of the Dublin Post Office building, headquarters of the Easter Rebellion, 1916, after the battle. Nearly 1000 Irishmen and British troops were killed in the uprising, with many of the weapons used by the Irish republicans being smuggled into Ireland from Germany.

Although unsuccessful, the rebellion had been supported by a large number of the Irish people, and public revulsion at the execution of 15 of the rebels caused an upsurge in electoral support for Sinn Fein. In the 1918 election, Sinn Fein candidates won 73 of the 106 seats allotted to Ireland in the British Parliament.

INDEPENDENCE - DE VALERA BECOMES PRESIDENT IN 1919

With such overwhelming support, the Sinn Fein members of Parliament met in Dublin in January 1919 and declared Ireland's independence, appointing Eamon de Valera as president.

Eamon De Valera, American born of a Spanish father and an Irish mother, De Valera returned to Ireland and became actively involved in Irish nationalist politics. He was arrested and condemned to death for his part in the Easter Uprising, but his American citizenship saved his neck. Released, he carried on with his struggle, becoming prime minister of an independent Ireland no less than three times.

The armed wing of Sinn Fein, called the Irish Republican Army (IRA) then launched a bitter guerrilla war against the British troops still in Ireland, particularly against an auxiliary police force known as the Black and Tans. This guerrilla war was waged with great ferocity on both sides, finally forcing the British parliament to agree to Irish independence with the Government of Ireland bill in 1920.

This bill provided for the division of Ireland into two - the majority of the land in the south (26 counties) as an independent state with status similar to that of Canada - and the six counties of the north retaining their status within Britain and becoming the province of Northern Ireland.

Sinn Fein split over the division of Ireland. De Valera was opposed to the partition of Ireland and led 57 Irish MPs against the bill against the 64 who were in favor. De Valera resigned as president and was replaced by the founder of Sinn Fein, Griffiths.

Michael Collins, the Irish patriot who had virtually single handed created the IRA, came out in favor of the settlement and became chairman of the provisional government.

THE IRISH FREE STATE - 1922

A civil war broke out in Ireland between those supporting the partition and those opposed to it. Hundreds were killed in the war, including Collins himself.

The civil war did not halt the establishment of the Irish Free State, and in December 1922, a new constitution became effective through which the state formally came into being.

The next year, the civil war was ended when De Valera agreed to accept the partition of Ireland as a compromise. He was elected to parliament, and by 1932 he had once again been voted in power as president of Ireland. De Valera then instituted a series of measures designed to further reduce the last vestiges of British influence. Finally in 1937, a new constitution was adopted which further loosened British control and formally created the republic of "Eire". De Valera was elected prime minister.

THE SECOND WORLD WAR - IRELAND CONDOLES HITLER'S DEATH

Officially, Ireland remained neutral during the Second World War, but in reality the island split - many Irish worked in British factories, replacing British men called up for active service, while others either openly sympathized with Germany or actively tried to aid the German war effort. In this way Eire became the only country in Europe to send an official telegram of condolence to Germany after the death of Hitler in April 1945. It seems likely however that the Irish actions were motivated more out a dislike of the British rather than support for the Germans.

On Easter Monday, 18 April 1949, the anniversary of the Easter Rebellion, Eire became the Republic of Ireland, formally free of allegiance to the British crown and no longer a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

IRA REFOUNDED

Although it had never been formally disbanded, the IRA was revived during the post war period as violence between Catholics and Protestants in the six counties of Northern Ireland increased during the 1960s.

The IRA then launched a new war to drive the British out of Northern Ireland. The issue was not however as clear cut as it had been in the southern part of the island, due to the very large number of loyal British Protestant subjects in the six counties.

In sheer terms of numbers, the Protestants were in fact in the majority, and viewed Catholicism as being synonymous with Irish nationalist rule - hence the loyalist/republican divide was created in Northern Ireland.

Attacks on loyalist Protestant civilians led to the loyalists forming their own paramilitary organizations, and soon several towns in Northern Ireland were divided into Catholic or Protestant areas. It became dangerous for Catholics to go into Protestant areas, and vice versa - loyalists versus Irish nationalists, a heady brew caused by a split in Christianity (sparked off by Henry VIII's desire to get divorced) and a conflict of Irish and British nationalism.

British troops face a stone throwing mob in Ulster in the 1970s - the legacy of centuries of English/Irish conflict. The 1980s were marked by a large number of spectacular IRA attacks on the British mainland. Attacks on blatantly civilian targets such as bars and shopping centers in particular, provoked wide scale outrage in Britain.

During the 1970s, the IRA moved on to start bombing strategic and civilian targets on the British mainland, causing outrage when bars and public places were bombed without warning. During the late 1990s, the warring factions were brought to a table and the beginnings of a settlement were thrashed out.

RACIAL HOMOGENEITY

Despite a small influx of Nonwhites, Ireland has to a fairly large degree kept its racial homogeneity in the late 20th Century. Nonetheless, the issues of Third World Nonwhite immigration also confront Ireland, and are dealt with in the last chapter of this book.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.