MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 38 : GOTT MIT UNS - THE RISE OF GERMANY

The history of Germany since the fall of Roman Empire is a story of internal intrigue, international bickering, religious wars, steady technological and artistic development - and a cycle of division and unity.

The level of infighting which occurred amongst the Germans during their history is noticeably much higher than in virtually all of their neighbors. This is a reflection of the highly individualistic nature of the Germans themselves, and in reviewing the progress of that nation it can be rightly said that the fact that they achieved unity at all, is a miracle in itself.

The only common thread amongst the centuries of internecine war was a refusal by all of the Germans to allow foreigners into their lands. This tradition ensured that Germany remained one of the most racially homogeneous societies on continental Europe until the last quarter of the 20th Century when a dramatic change in policy occurred.

This high degree of homogeneity played a significant role in ensuring that the Germans survived their period of bitter civil wars and the otherwise devastating religious wars.

CHARLEMAGNE AND WIDIKUND'S REBELLION

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire - and its sacking by Germanic tribes - Germany was left to its own devices until the 8th Century, when Charlemagne, king of yet another originally Indo-European tribe called the Franks, gained control of France and southern Germany. Largely as a result of Charlemagne's genocidal evangelism (detailed in an earlier chapter) most Germans had become, in theory at least, Christians by the 9th Century. Charlemagne's empire did not long survive his death in 814 AD.

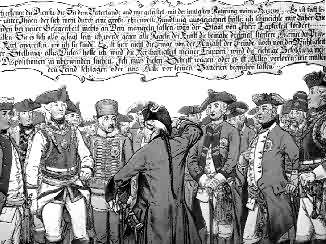

The submission of Widikund and the Christianization of Germany. When the Frankish King Charlemagne set about destroying White paganism amongst the German tribes, he knew that it was most important to first get the leaders of the tribes to convert to the new religion. While many did not convert - and were put to death - enough did convert to allow Christianity to become established in Germany. One of the bitterest opponents of Christianity and of Charlemagne in Germany itself was Widikund, who led a revolt while Charlemagne was fighting in Spain against the Nonwhite Moors.

Supported by other Germanic tribes such as the Danes, the Frisians, Prince Widikund attacked the Christian colonies that Charlemagne had set up in Thurungia and Hesse, utterly destroying them. Charlemagne exacted a terrible revenge, and finally captured Widikund, forcing him to submit to baptism into Christianity in 785 AD. This picture shows Widikund finally being forced to bow before the Frankish king.

Battered by Viking invasions which soon reduced most of the outlying areas to shambles, the empire was divided up amongst his three grandsons by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, with one grandson receiving West Francia (modern-day France), another receiving the imperial title and an area running from the North Sea through Lorraine and Bourgogne to Italy.

The third, Louis the German, received East Francia, which became the modern day Germany. East Francia was itself divided up into a number of independent and semi-independent fiefdoms.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE GERMAN STATES

By ancient tradition, German kings were elected on a tribal basis, and this tradition continued, with any number of tribes each electing their own king and establishing their own kingdom. In this way Germany was steadily divided up into a number of small states.

Despite the division of the land into a number of states - which varied between 200 and 340 in number, depending upon the period of history considered - the Germans continued with the tradition of electing an overall king, whose powers of interference in the individual states varied greatly from region to region.

The right of electing a king was held at first on a local level by each tribe, whose elected nobles then in turn elected, usually from within their own numbers, an overall king. By the late 13th Century, these states had more or less been firmly established and the right of electing their kings had been limited to a small number of local nobles, the so-called Seven Princes.

THE FIRST REICH - THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE INCLUDES ITALY

In 936 AD, the German princes elected Otto I, the son of a Saxon Duke, as King of the Germans. Otto was, through a combination of diplomatic skill and military ability, able to ensure the loyalty of many of the German states and was instrumental in fighting off the great Nonwhite invasion of Asiatics in a great race war by defeating them at the battle of Lechfeld in 955. (This Asiatic invasion was dealt with in previous chapter). Otto also had to fight off attacks from the Danes and Slavs, defeating them and establishing German centers in the lands he occupied as a result - the most prominent being the archbishopric of Magdeburg in 968 AD.

The First Reich: the coronation crown of Otto 1, the Emperor of the re-established Holy Roman Empire.

By these deeds Otto virtually single-handedly created the Holy Roman Empire. Although this title had been given first to Charlemagne and his kingdom, it took on real and lasting meaning following the exploits of Otto in Italy.

Italy had earlier been invaded by a fierce Germanic tribe called the Lombards. They had, apart from pushing the remnants of the mixed race Romans down into the south of Italy, established the great city states of northern Italy and had set up the Kingdom of Lombardy.

In 951 AD, the King of Lombardy died and his widow, Adelaide, was seized by an usurper, Berengar. Adelaide managed to escape and asked Otto for help against her former captor. Otto then invaded northern Italy and occupied Lombardy. Not being one to turn down an opportunity, Otto then married Adelaide and took her dead husband's title, formally adding northern Italy to the lands ruled by the German king.

The Catholic Church at this stage was under increasing pressure from independent Lombard nobles in the north and by invading Byzantine Greeks and Moors ("Saracens") from the south of that country.

When Pope John XII appealed to Otto for aid against Berengar, Otto invaded Italy a second time, defeated Berengar, and was crowned Emperor by the Pope in 962. This was how the Holy Roman Empire was created - out of a loose association of German states and northern Italy, a dispensation which would last in name until 1815.

Otto's successor, Otto II, re-established Charlemagne's Eastern March (Austria) as a military outpost but was defeated by the Nonwhite Moors in his efforts to liberate southern Italy from Islamic rule.

MEDIEVAL GERMAN SOCIETY - KINGS HAD NO FIXED CAPITALS

German kings had no fixed capital city and continually traveled around the greater German territory making up the Holy Roman Empire, being granted shelter and support by the German princes who retained for the greatest part rule in their own respective states. The vast majority of common people lived as agrarian peasants in a feudalistic system. The few cities, such as Trier and Cologne, were populated by merchants, artisans and uprooted peasants, the latter settled as free citizens under the authority of a prince.

THE POPE'S WORD IS FINAL

From the time of the establishment of Otto's Empire, the Pope in Rome came to play an increasingly important role in German affairs. Papal approval was required for each king's appointment. Often civil war would break out based on whether the Pope's approval (or otherwise) had been given for any particular event.

The reign of the German King Henry IV (at the beginning of the 11th Century) serves as a good example.

A series of conflicts with the Pope resulted in the Church officially withdrawing its official support from Henry IV, causing several German states to refuse to recognize his kingship. This sparked off nearly 20 years of civil war when rebellious German princes elected a new king, Rudolf, from their numbers while Henry was still alive.

In such cases - and it happened more than once - the German king would march on Rome, seize the city and depose the offending Pope, replacing him with one more favorably disposed. The most prominent of such events occurred in 1080, when Henry IV deposed the resident Pope - and in 1175, when Frederick I occupied Rome and threw an uncooperative Pope out of the Vatican.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, Germany and Italy were racked by endless internal squabbles over the succession to the throne, with the Church officially intervening every now and then in camps in which it saw the greatest benefit. These squabbles resulted in yet more localized civil wars, interrupted only by the occasional participation in the crusade and an anti-Jewish riot.

FREDERICK BARBAROSSA - INVADED ITALY FIVE TIMES

Finally a king was elected whose parentage came from almost all the competing princedoms. Frederick I, also known as Barbarossa, spent most of his reign trying to consolidate the Holy Roman Empire, fighting with upstart German and Lombardic nobles in Italy and Germany. In all Frederick invaded Italy five times, being defeated the last time at the Battle of Legano in 1176. The emperor's rule was slightly dissolved as a result, with some cities in Italy for all practical purposes achieving their independence, being only nominally subject to Frederick, who finally died while on the Third Crusade.

The Emperor Frederick Barbarossa entering Milan. The continuing duel between the German kings and the Pope continued to rage through the centuries. In 1157 a dispute arose between Barbarossa and the then Pope, and in the following year the German king crossed the Alps with an army and forced the city of Milan to submit to his power. Eventually Barbarossa was to wage several more serious quarrels with the Church until he finally died while on the Third Crusade.

FOUR ISSUES DOMINATE

From the time of Frederick Barbarossa to the beginning of the 19th Century German history was dominated by four major issues:

Holding the Holy Roman Empire together in the face of continual rebellions by German and Lombardic princes. (This situation was complicated when the Normans, descendants of Vikings, who had settled in north western France, established an outpost in southern Italy and Sicily. The Normans proved resilient foes, and allied with the Lombardic princes, led to more than one German military expedition in Italy floundering.);

Fighting successive race wars against invading Nonwhite Turks in central Europe, Sicily, and going on the Crusades;

Fighting a seemingly endless secession of European wars in a never ending combination of alliances and enemies; and

A devastating series of Christian Wars, which saw Catholics and Protestants killing each other in the name of Jesus Christ.

OLDEST GERMAN UNIVERSITY FOUNDED IN PRAGUE

During the course of the wars in Sicily, the German King Frederick II, the Stupor Mundi ("wonder of the world") established a large German settlement on that island, which made a not insignificant further contribution to the small Nordic segment of the population.

Frederick II also founded the University of Naples on the southern Italian mainland. In 1347, Charles IV, king of Bohemia, was elected king of Germany and he turned his capital city, Prague, into a lavish court city, building many beautiful structures which can still be seen today, and establishing the oldest German university in the world in that city.

Despite the civil wars, the German population continued to grow fairly normally, with the first significant hiccup in the growth pattern occurring with the outbreak of the bubonic plague - the Black Death - which struck all of Europe in the mid 14th Century. An estimated one third of the German population died in the Black Plague.

THE POPE'S AUTHORITY REJECTED

Endless civil wars raged until a meeting of German princes at Rhense in 1338, revoked the right of the Pope to approve the German king. From then on civil war would be avoided by letting the king be elected by simple majority vote amongst the German princes without papal intervention. This significant shift was reflected in the title, official in the 15th Century, Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation, much to the protest of assorted Popes, who were ignored.

THE HOUSE OF HABSBURG - 1273 AD

In 1273, Rudolf I of the House of Habsburg was elected emperor. This marked the creation of one of the strongest German dynasties. When the princes elected the first member of the house of Habsburg in 1418 as Emperor, Albert of Austria, another shift occurred in the process of selecting kings - for the first time the crown became hereditary in the Habsburg line.

This shift occurred in practice and not by law. By the 15th Century, through marriages between Habsburgs and other noble families in Europe, this Royal House had acquired vast territory that consisted of most of central Europe and colonies in America. By the time that Charles V became Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, there were more than 200 different German states mostly ruled by local princes.

THE REFORMATION - LUTHER BREAKS FROM THE POPE

Germany was then to be shaken by a revolt within the ranks of the Church itself. Fed by the growing dissension already expressed in the rejection of the Pope's authority over the election of the German king, objections then became increasingly common against the sale of indulgences by the church.

These indulgences were in effect the church selling their God's forgiveness in exchange for cash - this blatantly corrupt process led to an Augustinian priest, Martin Luther, leading a protest against Catholic excesses. Luther made a point of attacking the sale of indulgences by the Church - money for remissions of punishment for sin.

In 1517, Luther published a list of 95 theses attacking indulgences, following this up with the publication, in 1520, of three pamphlets proclaiming the liberty of the Christian conscience. The Pope of the time, Leo X, issued an order (a "bull") condemning Luther's works. Luther burned the bull and was then excommunicated.

The German emperor, Charles V, summoned Luther to defend himself at the Diet of Worms (1521) and, when Luther refused to recant, he was outlawed. On his way home, however, Luther was rescued by Frederick the Wise, elector of Saxony. Installed in the Wartburg castle, he began to translate the Bible into German.

Luther's works ultimately led to the reformation and the split in Christianity. The outbreak of the Christian Wars which saw yet another third of Germany's population slaughtered by opposing factions of Christians all claiming to have the final truth. The sad tale of the Christian Wars is recounted in a later chapter.

Luther's followers, known as Lutherans, and other reformers, known generally as Protestants, included German princes who established state churches supported by lands confiscated from the Roman Catholic church.

After leading troops against the Protestant princes and cities, Charles V agreed to the Peace of Augsburg (1555). It gave each prince the right to choose the religion for his territory.

THE NONWHITE INVASION - 1663 AD

In the midst of the religious upheavals, the Nonwhite Turkish invasion of Europe, which had been gathering pace since the city of Constantinople had been overrun in 1453, dominated German foreign affairs. When the Turks invaded Hungary in 1663, German troops defeated the Nonwhite invaders.

The Turks waited another 20 years before trying again. In 1683, the Turks invaded Austria itself, besieging Vienna in 1683.

German and Polish troops relieved the city before it fell, driving the Turks beyond the Danube, with the result that Hungary was obliged to recognize the Habsburg right to inherit the Hungarian crown.

The war against the Nonwhite Turkish invasion continued until the victory of Prince Eugene of Savoy at Senta in 1697.

The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, saw the Habsburgs regain most of Hungary, with the depopulated country being resettled with German veterans.

THIRTY YEARS WAR - ONE THIRD OF POPULATION KILLED IN THE NAME OF CHRISTIANITY

In the interim, Christianity caused the Germans to once again turn on themselves with a vengeance. Eventually a conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Germany led to a devastating, four-phase European War known as the Thirty Years' War. The losses incurred by this war were staggering - in all one third of all Germans were killed, either directly through war, or indirectly through related famine and plague. In Bohemia alone, one half of the population died.

The rise of Protestantism in Germany was soon checked by Jesuit priests, who won many Germans back to Catholicism, and by south German princes, who restored Catholicism by force. Other European nations took advantage of the quarreling German states to intervene, making Germany the scene of a devastating four way conflict. The war ended with the recognition of the sovereignty of each state of the empire, which made the emperor virtually powerless.

MORE WARS - MORE TERRITORY ACQUIRED

The peace which followed the Thirty Years War was brief. Nonetheless some new lands were seized by the German states still powerful enough to engage in foreign adventures. Most notably portions of Poland were seized by some eastern states, while others consolidated themselves by including in their borders some neighboring smaller German states.

Scarcely had they recovered from the Thirty Years' War when the German princes and the emperor plunged into a variety of new dynastic struggles. The French, the Dutch, and some German states all became involved in a war known as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) which was fought over the a German king's right to inherit the Spanish throne. Large armies wreaked havoc in Bavaria and western Germany until the wars ended with the Peace of Utrecht in 1714.

Frederick the Great (1712 -1786). Certainly one of the greatest military geniuses in the history of the world, he fought time and time again against enemies who were numerically superior - including odds of 20 to one.

Frederick the Great of Prussia making his famous address to his generals before the Battle of Leuthen, 3 December 1757. He told them that he had devised a plan to attack their opponents, an Austrian army, that was 'twice as strong as ourselves and entrenched on high ground. I must do it, for if I do not, all is lost. We must defeat the enemy, or let their batteries dig our graves.'

Frederick then laid out his plan and invited dissent from any of the generals : 'This is what I think and how I propose to act. But if there is any among you who thinks otherwise, let him ask leave here to depart. I will grant it to him, with out the slightest reproach.'

Not one general left. Frederick continued : 'I thought that none of you would leave me - so now I count entirely on your loyal help, and on certain victory. Now go to your camp and tell your regiments what I have said to you here . . . The cavalry regiment that does not charge the enemy at once, on the word of command, I shall have unhorsed and turned into a garrison regiment. The infantry regiment which begins to falter for a moment, for whatever reason, will lose its colors and is swords, and will have the braid cut off its uniforms. Now gentlemen farewell, by this hour tomorrow we shall have defeated the enemy, or we shall not see one another again.'

The Battle of Leuthen followed - and Frederick won, despite the Austrian superiority. On the evening of the next day, on the snow covered, blood stained ground of Leuthen, a lone Prussian soldier began to sing an old hymn, Nun dankt alle Gott - Now Thank we all our God. Amongst the groans of the wounded and the dying, the entire Prussian army took up the hymn - more than 20,000 men. Even Frederick, a well known atheist, was moved.

THE PRUSSIAN-AUSTRIAN CONFLICT

By the beginning of the 18th Century, the German states of Austria and Prussia had emerged as the biggest and strongest - and both entered into a competition for leadership of all of Germany. The first phase of this conflict was the War of the Austrian Succession, fought from 1740 to 1748 over the right of the child of the Habsburg Emperor Charles VI, Maria Theresa, to inherit parts of the Empire, notably Silesia, which Prussia wanted.

The Prussian invasion of Silesia in 1740, sparked off a major war, with the Bavarians, the Saxons, and French invading Austria and Bohemia, while Britain, the Netherlands, and Russia came to the aid of Austria.

The war ended in defeat for Austria and her allies, and Prussia annexed Silesia, although Austria did gain Bavaria. The Austrians however started preparing a revenge attack, and made an alliance with Russia.

The Prussian king, Frederick I (known to history as "Frederick the Great" - one of the greatest military geniuses the world has ever seen), anticipating that he was being encircled, invaded Saxony and Bohemia in 1756.

This launched a war called the Seven Years' War which lasted until 1763. The Austrians responded by invading Silesia - the Russians invaded Prussia itself and the French attacked Hanover.

Prussia was almost beaten but rescued at the last moment by the sudden death of the Empress of Russia, Elizabeth, and her replacement with Peter III, who was an admirer of Frederick and at once made peace. All the sides, exhausted, made peace and the status quo before the start of the war was restored.

GERMANS LEAVE

The endless series of pointless wars and the increasingly high taxes imposed upon the peasantry and working class Germans by the German princes as a result of these wars, resulted in a massive population shift out of Germany to the newly discovered Americas.

This emigration reached such numbers that eventually Germans were to make up as much as 60 per cent of all White Americans.

The price of petty nationalism is vividly demonstrated by German history: Until 1870 the German were as wont to go to war with each other just as soon as with anybody else. The struggle for supremacy between Prussia and Austria ended in victory for Prussia. Prussia did not however have all her own way. Above left : Soldiers from the state of Hanover, in alliance with the Austrians, clash with the Prussians at the Battle of Langensalza on 27 June 1866. The Austro-Hanoverians held the field and gained a considerable victory over the Prussians. The Prussians were however to inflict several decisive defeats upon the Austrians, notably the Battle of Skalitz on 28 June 1866, where Austria lost a quarter of its army killed in the field. The picture right shows Prussian cavalry capturing the Austrian cannon.

GERMAN CULTURAL GENIUS

This period of German history was also the time of some of the world's most famous artists: the classical composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, J.S. Bach; Ludwig van Beethoven and a host of others lived during this time, writing music which is still regarded as works of genius hundreds of years later.

Two German artistic geniuses - left: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), the Nordic Austrian-German musical genius, depicted here as a child prodigy. He had learned the piano at four, and undertook his first European concert tour at six. His first opera was written when he was 12. Right: Ludwig van Beethoven, (1770-1827) is universally regarded as the greatest composer of all time, composing most of his masterpieces while he was completely deaf.

NAPOLEONIC WARS

At the beginning of the 19th Century, the German states found themselves engaged in 18 years of warfare against the revolutionary and then Napoleonic French armies. After Napoleon had occupied Vienna, Berlin and Moscow, the Germans managed to defeat the French at the battle of Leipzig in 1813, and invade Paris as part of a joint Prussian/Russian/Austrian offensive. Although Napoleon was defeated, the ideas of liberty and nationalism which he spread were to lead to a number of revolutions across Europe - and Germany was no exception.

REVOLUTIONS OF 1830 AND 1848

At the Congress of Vienna, held from (1814-1815), the Holy Roman Empire was officially dissolved and replaced by a German Confederation represented by a powerless assembly.

The prominence of Prussia and Austria - in the form of the formidable Prince Clemens Metternich - prevented any democratic reforms being implemented in the confederation, even after the outbreak of the 1830 revolution in France, which set off liberal uprisings in many German states - which were effectively suppressed.

In 1848, another wave of revolutions, beginning in Paris, engulfed much of Europe, and nationalist groups rebelled in Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Galicia, and Lombardy. Uprisings also took place in Bavaria, Prussia, and southwestern Germany, all demanding constitutional reforms in the direction of democratic government.

Prince Metternich resigned and the shocked German princes agreed to send delegates to a congress in Frankfurt to address the issues raised. The congress however became known as the "do-nothing" congress, as it did precisely that.

The rebellions were soon crushed, with a liberal constitution being dissolved in Austria and a constitution providing highly centralized, although representative, government being imposed. Hungary, which had declared itself a republic, was forcibly subdued.

GERMAN UNIFICATION UNDER BISMARCK

In Prussia, William I imposed an authoritarian constitution and together with his able chief minister, the famous Otto von Bismarck, put into working an audacious plan to unite Germany under Prussian leadership.

Bismarck invented "realpolitik", combining diplomacy with militarism to ensure Prussia's supremacy, First, ensuring the neutrality of Russia, Italy, and France with treaties, he then invited Austria in 1864 to join an invasion of Schleswig-Holstein, two German states ruled by Denmark.

The Austrians and Prussians quickly defeated the Danes, but soon fell out over control of the conquered territories. Bismarck then launched the Seven Weeks' War against Austria in 1866, with the famous General Helmuth von Moltke defeating the Austrians.

In terms of the peace treaty which followed, Bismarck let Austria off very lightly - Austria gave up Venetia to Italian nationalists while Prussia annexed Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover, and other states and organized the North German Confederation, which formally came into being in 1867.

Kaiser Wilhelm 1 of the first united Germany in history. King of Prussia when that state came to be the premier German state, he was declared Kaiser ('Caesar') of united Germany on 18 January 1871.

THE FRANCO-PRUSSIAN WAR - FRANCE CRUSHED

In 1870, Bismarck maneuvered France into declaring war on Prussia and the North German Confederation over the issue of secession to the Spanish throne.

Propelled by a growing national loyalty, the still independent southern German states backed Prussia. The well trained, well armed and now experienced Prussian army made short work of the French at the famous Battle of Sedan and then made straight for Paris, which was besieged and occupied in 1871. The war ended in total victory for the Prussians.

THE SECOND REICH - A UNITED GERMANY

The ease with which Prussia had beaten the French did not go unnoticed by the southern German states - they fell in line and became part of a unified Germany, whose new emperor, or Kaiser (Caesar), Wilhelm I, was crowned in the Palace of Versailles in 1871. The Second Reich had been created.

The united Germany was Bismarck's creation, and it was universally acknowledged as such. Under his chancellorship, the industrial revolution in Germany took hold, making Germany one of the world's foremost industrialized countries.

The population rose by one third, recovering substantially from the draining wars of the 17th and 18th centuries. Virtually no foreign laborers from anywhere entered the country, helping to maintain the highest degree of racial homogeneity of any major continental power at the time of the beginning of the 20th Century.

Otto von Bismarck, the creator of the Second Reich and uniter of Germany.

BISMARCK SEES CATHOLIC CHURCH AS THREAT TO GERMAN STATE

Bismarck was also keenly aware of the divisive influence the Catholic church had exercised in German history. Bismarck believed, quite correctly, that the Catholic church, which had declared the infallibility of the Pope in 1870, threatened the supremacy of the German state. He therefore started what became called the Kulturkampf ("culture struggle") during which many religious orders were dismissed, their members imprisoned, or exiled. Bismarck also tried to abolish the growing socialist party in Germany, but before he could do so he was dismissed by the new German Kaiser, Wilhelm II.

The age of the unification of Germany saw the great musical traditions of Germany taken to new heights. Franz Peter Schubert, Johannes Brahms, and Richard Wagner were all composers of note during this period.

FIRST WORLD WAR - GREAT LOSS OF LIFE AND KAISER DEPOSED

As a result of colonial competition, inter-European rivalry and growing nationalism, Europe became increasingly divided. By 1907, the continent was split into two camps: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria, and Italy, and the Triple Entente of Russia, France, and Britain. The creation of these alliances contributed to the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918).

The course of that catastrophic war, which saw millions of Germans killed, is related in a later chapter. Suffice to say here that it ended in defeat for Germany and Austria with the signing of the Treaty Of Versailles in 1919 and the abdication of the last German king, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, the third and last Kaiser of united Imperial Germany. He came to the throne after the second Kaiser, Frederic, died after only three months in office. Wilhelm II was to reign from 1888 to 1918 - when the First World War ended the era of Imperial Germany. Wilhelm II fled into exile in the Netherlands, dying there in 1941.

In a climate reeking of revenge, Germany lost Alsace-Lorraine to France and West Prussia to Poland, creating a Polish Corridor between Germany and East Prussia. It also lost its colonies and had to give up most of its coal, trains, and merchant ships, as well as its navy. Germany had to limit its army and submit to Allied occupation of the Rhineland for 15 years.

Germany was also obliged to accept full responsibility for causing the war and, consequently, pay its total cost. This was an outrage, and the Treaty of Versailles came to be known in Germany as the Shame of Versailles. The Germans were no more guilty than anyone else for the war and could not possibly pay all that was demanded.

THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC - CATASTROPHIC INFLATION

The end of the war was marked by massive social unrest and Communist revolutions - most notably in the Communist Sparticus uprising in Berlin in 1919 led by the German Jewish Communists, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg.

Finally, a new constitution was written for Germany which included a democratically elected government. Called the Weimar Republic because the first parliament sat in that town, the new German state was racked by problems.

Although the state had been created by Socialists, it was opposed by hard line militant Communists as not being totally Communist, while on the right, groups of disaffected military groupings, arguing that they had been "stabbed in the back" by Communists at home while they were fighting on the front, launched their own coup, the Kapp Putsch of 1920.

In addition to dealing with armed insurrection, the Weimar republic faced severe financial crises. As Germany could not meet reparations requirements, France invaded the Ruhr in 1923 to take over the coal mines, using Black occupation troops. The German government encouraged the Germans to resist passively, printing vast amounts of money to pay them.

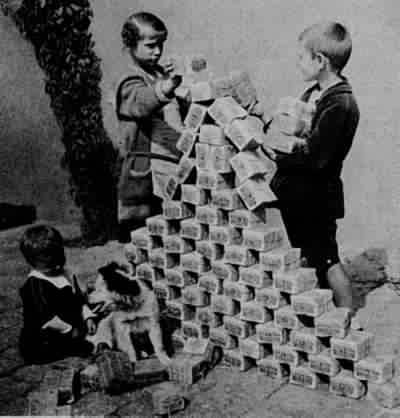

Devaluation: German children play with bundles of worthless banknotes, 1924. Below, a 500 million Mark inflation banknote from 1923. An example of the worthlessness of German currency during the hyper inflationary period of the Weimar Republic. Although nominally of huge value - 500 000 000 marks, it would barely buy a loaf of bread, and its currency expired on 1st September 1923.

The resulting inflation, combined with the effects of the Great Depression which started in 1929, wiped out savings, pensions, insurance, and other forms of fixed income, creating a social revolution that destroyed the most stable elements in Germany.

ADOLF HITLER - SAVES GERMANY FROM COMPLETE COLLAPSE

Millions of Germans then turned to either the Communist Party or the National Socialist German Workers' Party of Adolf Hitler - eventually Hitler was legally elected to office by a democratic vote and became supreme ruler of Germany.

The heavy preponderance of German Jews in both the offices of the hated Weimar government and in the German Communist Party, fed the anti-Communist and anti-Jewish sentiment in Germany, something upon which the National Socialist (in German the National Sozialist - or Nazi) party was able to capitalize. The significance and effect of Hitler's Germany has been massive, and is detailed in a later chapter.

THE SECOND WORLD WAR - HUGE POPULATION LOSS

The Second World War was possibly the single largest conflict of all time. The losses suffered by Germany were staggering - some seven million Germans were killed, either as combatants or civilians who died in the resultant carpet bombing of Germany.

As a result of the brutal expulsion of Germans from the eastern territories at the end of the war, some two million civilians perished. Additionally the Western Allies managed to starve to death nearly 800,000 German POW's. In total, seven million Germans died unnaturally in the period from 1945 to 1950.

GERMANY OCCUPIED

At the end of the Second World War, Germany's territory was drastically reduced in size and divided up into four occupation zones which eventually crystallized into the democratic Federal Republic of West Germany and the Communist dictatorship of the German Democratic Republic, better known as East Germany.

The division between East and West Germany became the focal point of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. The Communist controlled East Germans built a wall around the divided city of Berlin in an attempt to prevent the growing flood of East German refugees from fleeing into western territory. The Berlin Wall became a symbol of the Cold War, with some 3000 Germans being killed trying to cross the wall.

GERMAN REUNIFICATION

The fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the Communist power bloc saw the wall being torn down by a deliriously happy German mob in 1989. In October 1990 East and West Germany were formally re-united, boosting the German population to approximately 80 million - including at least 7 million non-German guest workers, or "gastarbeiters".

Germans dance on the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989. A week previously and they would have been shot by East German border guards. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990 symbolized not only the unification of Germany, but of the fall of Communism. Unification brought with it however a host of new problems, including an economic burden for the former West Germany as it struggled to bring the virtually wrecked former Communist East Germany economy on board. The new Germany has also had to deal with huge numbers of legal and illegal immigrants, many of them taking advantage of that country's very liberal asylum laws, which were eventually changed as the flood of asylum seekers from Nonwhite countries became ever greater.

In October 1993, Germany became the 12th and final nation to ratify the Treaty on European Union, also known as the Maastricht Treaty. In 1994, the last Russian and Allied troops left Berlin, the first time in 49 years that there had been no foreign troops occupying the city.

POPULATION SHIFTS

It was only in the last quarter of the 20th Century that Germany, like its European neighbors, began to allow Nonwhite foreigners into its borders in any significant numbers, mainly from Turkey but also of late from Africa and Asia. At the end of the 20th Century, fully 10 percent of the German population was Nonwhite. These developments and their significance are discussed under a separate chapter.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.