MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

Chapter Forty Nine

The Birth of the United States of America

Although the United States did not emerge as a separate country until the end of the 18th century, it assumed a massive, perhaps even dominating, role in world history from that time onwards. North America became as important as Europe in many senses: not least because it became, through occupation and natural reproduction, a new White heartland, mirroring the occupation of Europe by the Indo-Europeans some 7,000 years earlier.

First Settlements

Recent archeological finds in North America indicate a White presence on that continent many thousands of years old - this was dealt with in chapter six of this book. The next wave of Whites to set foot upon the North American continent during the 11th century were the Vikings, and then later in the 15th century by the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. Based on Columbus's voyages, Spain went on to claim large areas of north, central and southern America for itself. On the basis of Cabot's voyages, England later claimed the entire north America, coming into conflict with French explorers who had also staked out pieces of land for themselves.

The French had established small colonies in Quebec and some northern territories such as later day Newfoundland, and had claimed a huge area of middle America following the Mississippi River south right down to Louisiana. The French however did not settle the area in large numbers, choosing instead to set up trading stations and not displacing the native Americans.

Effect on Amerinds

However, the very first racial consequence of the arrival of large numbers of White settlers in North America was an unintended decimation of the local population: the American Indian (Amerinds). This was done by the introduction of new diseases to North American, borne by the White settlers: influenza, typhus, measles, and smallpox were not necessarily fatal to Whites, but were deadly to the Amerinds who had no prior experience of them and thus had no innate resistance. The Amerinds died in large numbers: some estimates say as high as 40 percent. The exact figure will however never be known, as the original number of Amerinds is unknown.

Then the White settlers introduced livestock and horses to America: these domesticated animals took land away from the indigenous game animals, such as the bison: this combined with a later deliberate policy of reducing the numbers of bison, deprived the Indian hunters of a major source of their food.

Scalping

By 1630, the Spanish, French, Dutch and English had all established colonies in North America: all except the French had found themselves waging racial wars against the Amerinds, who resisted the White settlers with methods which were by any standards cruel. This was the first time the Whites came into contact with the particularly nasty habit of scalping - the taking of the scalp of a defeated enemy as a trophy; a habit deeply ingrained in the Amerind culture of war.

Pilgrim Fathers

Although North America had therefore been settled by loose groups of Whites, the formal founding of that country was counted as starting with the arrival of a group of English religious refugees, the Separatists (also later known as the Pilgrims) on board the ship the Mayflower, off Massachusetts Bay in 1620.

The Separatists were one of the English Christian dissident groups who argued that the Anglican Church had not split far enough from the Catholic Church - and found themselves hated by both Catholics and Protestants alike. Finally they obtained permission to settle in the British colony of Virginia (the British government was no doubt glad to see the back of them, and Virginia had become a gathering point for all elements of unwanted British society).

However, either through deliberate design or navigational accident, the good ship Mayflower missed Jamestown, Virginia, and threw anchor off the coast of Massachusetts in what is now the harbor of Provincetown in November 1620. Despite the fact that they were in land outside of any colonial power, the pilgrim fathers landed their small group and founded a settlement near present day Cape Cod, called the Plymouth Colony (after the port in England from where the Mayflower had sailed).

The Plymouth colony became a lightening conductor for all manner of Christian dissidents seeking religious freedom. Between 1629 and 1640 - only eleven years - over 25,000 English dissidents alone immigrated to the new lands.

The Salem Witch Trials

Exactly how fanatical were many of the early Christian settlers, and as an illustration of just how badly they were infected with the worst excesses of that religion, was illustrated by the Salem witch hunt, which took place in colonial Massachusetts in 1692. Through this lunacy, the town of Salem became the holder of the dubious honor of being the site of one of the last ever witch hunts which took place in the Western world.

A perfectly innocent game of witches being played by some young girls set off the Christian fanatics in the town to the point where mass hysteria broke out: no less than twenty unfortunates were arrested and charged with being "witches" - a charge against which it was impossible to defend oneself properly. All were burned at the stake after being found guilty of the most ridiculous charges imaginable. The absurdity of the situation must have been realized by many in the wider settlements: after Salem there would never be another Christian witch hunt on that scale in America again.

Massachusetts Bay

In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established by an English company in terms of a specially granted charter. The authority contained in this charter gave the colony virtual self government, and very soon this authority was used to expel some Christian dissidents from this already dissenting Christian colony: the now twice expelled Christians formed the basis of the settlement from which Rhode Island grew.

In 1636, the demand for more cattle grazing land pushed a large number of settlers westwards, displacing Amerinds and founding Connecticut. Further streams of White settlers continued to arrive in North America: Catholics settled in the territory called Maryland by them in honor of the biblical mother of Jesus.

Dutch Possessions Seized

In 1663, another English company was granted the charter of what is now North Carolina and South Carolina. The Dutch colony of New Netherlands was occupied by English troops in 1664 and renamed New York. New Jersey was also taken from the Dutch in the same year.

Captain John Smith, one of the early settlers in Virginia, shown seizing an Amerind chieftain. Legends grew up around Smith to the effect that he fell in love with an Amerind girl, Pocohontas. These stories are extremely exaggerated: in fact Smith was an old man who used a young Amerind female for sexual purposes and no more.

Metacom's War

The Amerinds living in these areas for the greatest part resisted the White settlements with violence. The last resistance to the Whites in New England came in 1675, when three Amerinds were executed by the White colonists for murder. An Amerind chief named Metacom, but who was also known as King Philip, led an alliance of Amerind tribes in fierce guerrilla raids on the colonists after this: the Whites replied in kind and a bloody tit-for-tat exchange followed until Metacom's secret hideout was discovered and he was killed. The Whites then drove the majority of remaining Amerinds from New England.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire was created in 1679 out of the fringes of the colony of Massachusetts, while in 1681, the Englishman William Penn received a charter for the region that he immodestly named Pennsylvania. Although all of these territories were still nominally British, internal conflict in Britain itself kept the British monarch from exerting any effective control until 1676.

Until then the founding charters of each territory allowed the settlers to form more or less their own system of government: this combined with the refugee mentality of many of the original founders, created a sense of individualism and self enterprise which would later not only lead to the American War of Independence, but also the characteristics by which America came to be known throughout the world.

Mass White Immigration

As news of the colonies in the Americas, or the New World, as it became known, spread throughout Europe, there occurred one of the most incredible mass population movements since the Indo-European immigrations: hundreds of thousands of Whites from virtually every country in Europe packed up their bags and moved to the new territories.

Some were attracted by the opportunity of owning their own land - something impossible for common folk since the time of feudalism in Europe - while others wanted to escape the class systems and religious conflict into which Europe had descended. Waves of Germans, Irish, Danes, Dutch, Swedes and others all started pouring into the colonies, even though they were still under the nominal control of England.

English Laws Resented

Internal political developments in Britain started to effect the colonies in America after the English civil war of 1642. The first English law concerning the colonies was the Navigation Act of 1651, which required that colonial imports and exports be shipped in English-flag vessels. Ultimately the British monarchy started trying to exert greater influence on the colonies - primarily to try and prevent the loss of taxation revenue to the crown.

In 1684, the charter to Massachusetts was revoked as punishment to that state's inhabitants violating the trade provisions of the Navigation Act. In 1686, the British king, James II, ordered that the states of New York, New Jersey, and New England be unified into a single province, the Dominion of New England. Slowly dissatisfaction with the British king's interfering began to grow: Connecticut and Rhode Island refused to give up their charters to a governor appointed by the king, and in Massachusetts an armed rebellion broke out in 1689. Further rebellions occurred in Boston and New York City.

French and Indian War

A succession of European conflicts were then to further affect the state of the colonies: an inter-European war which was settled in 1713 by the Treaty of Utrecht, obliged the French to relinquish considerable territory, including Acadia, Newfoundland, and the region surrounding Hudson Bay to the British colonies.

Then yet another European conflict affected the colonies in America: increased tensions between the French, the Prussians and the English led to the outbreak of the Seven Year's War in 1756. The outbreak of this war led to the outbreak of the war known as the French and Indian War: in actual fact, several sets of wars between the French and British in North America which saw both sides ally themselves at various stages with tribes of Amerinds: the French being more successful than the British at this tactic.

The French had some distinct advantages over the British in North America: they had an experienced and well equipped army already stationed there, and their earlier policy of leaving the Amerinds alone paid off: they were able to form military alliances with the greater number of Red Indian tribes.

However, not all of the colonists under British rule had any great love for Britain. By 1775, the total White population of the British colonies was just under 2 million: but of these, approximately 1,2 million - or over 50 per cent - had come from other parts of Europe - mainly Germany and southern Ireland. Even those colonists who had come from England had more often than not left because of some gripe with that country, be it religious or social. The ties of allegiance to Britain were therefore from the outset very weak indeed.

British Reverses

The first three years of the Seven Year's War saw several British reverses in Europe: in North America too they were years of indecisive conflict, caused by the presence of a large group of Amerinds who lived in an area separating the territory held by France - which at that stage was still virtually all of what is today know as Middle America reaching down to Louisiana.

The Amerinds then became involved in the war, groups of them being allied to either the French or the British, with the confusing result that Amerind attacks on both French and English took place. Both White sides then started encroaching on the Amerind's neutral territory in an attempt to outmaneuver each other.

Tide Turns

After 1757, Britain and its allies in Europe and elsewhere managed to inflict decisive defeats upon the French forces: in North America, a British army, aided by colonial auxiliaries, seized Quebec in 1759, and in 1760, conquered Montreal: French power was at an end in North America.

The British-French War was concluded with the capitulation of France and the treaty of Paris: in terms of this treaty France was forced to cede large parts of her North American territories to Britain and Spain.

The Stamp Act

The financial strain of beating France caused the British government to look for more funds from the colonies: laws were stepped up to crack down on tax evaders. In 1765, the British government introduced the Stamp Act, which required American colonists to validate virtually all essential legal documents (including documents ratifying sales and purchases) by buying and attaching revenue stamps to these documents.

As this was an obviously gratuitous tax, it aroused great indignation amongst the American colonists, who felt hard done by after their contribution to defeating France during the war just finished. Protests broke out in virtually every city and town: civil servants who had been appointed to enforce the Stamp Act were forced to resign and thousands of the stamps themselves were burnt.

Sons Of Liberty

Secret societies of independence minded colonists calling themselves the Sons of Liberty were formed with the aim of stirring up dissent with the colonial government. In October 1765, colonists from all over the thirteen colony states met and declared their opposition to the Stamp Act: in 1766, the British Government repealed the law, but by then it was too late: the seeds for rebellion had been sown. Even so the British might have been able to keep the colonies under control, but then an inexplicable turnaround occurred; a new series of taxes were imposed upon the colonies: the Townshend Acts were passed in 1767.

British Goods Boycotted

These taxes demanded customs duties on tea, paper, lead, paint, and glass. In the American colonies, the flames of rebellion were fanned: British goods were boycotted, and in Massachusetts, the people of the town of Boston openly refused to adhere to the custom duty laws.

Boston Massacre

In response to this move, the British sent two regiments to Boston in 1768 - and tensions rose even further. On 5 March 1770, British troops fired on a crowd of protesters, resulting in what became known as the Boston Massacre: five colonists were killed and six were injured. The extent of the ill feeling caused the British to backtrack once again: in 1770, all the customs duties except that on tea were repealed - and the only reason why the tea tax was maintained was to keep the principle valid that the Crown had the right to levy taxes on the colonies.

The colonists then stopped the boycott of British goods - except for tea, which was maintained to keep up the right of the colonies to object to being taxed without being given representation in the British government. It should be borne in mind that by this stage the various colonies had, by virtue of their loose nature of their founding charters, begun to establish the first seeds of democracy, although this was by no means total. It was nevertheless an important mindset shift which laid the basis for the rebellion to come.

The Tea Act and The Boston Tea Party

Then in 1773, the British parliament passed a law granting the English East India Company the monopoly on tea sold to America. Known as the Tea Act, this law precipitated a new crisis in America : the colonists quite correctly regarded it as a way by the British government to force them to pay tax. In response, they intensified their boycott of British tea, and when three British East India Company ships loaded with tea entered Boston harbor in December 1773, a group of colonists, disguised as Amerinds, boarded the ships and proceeded to dump virtually the entire cargo into the harbor. This event became known as the Boston Tea Party.

The British reacted by declaring the port of Boston closed and prohibiting public meetings in Massachusetts. Discontent at the suppression of their right to protest, representatives of all the colonies gathered together in September 1774, for what was to be called the First Continental Congress. The Congress drew up a petition which was sent to the British king, George III, asking for a change in policy towards the colonies. At the same time the congress called for an intensification of a trade boycott with Britain, and resolved to meet again the next year if Britain refused to accede to their petition.

A Bad Move

George III then made the worst decision in the history of the British Empire: he rejected the petition out of hand and called upon his loyal subjects to suppress the rebellion. Within four months of his reaction being returned to the colonies, the rebellion to which George had referred did indeed break out: on 19 April 1775, some 700 British troops, marching to Concord in Massachusetts to destroy a store of weapons being hoarded by the increasingly militant colonist militia, were confronted by a group of 70 militiamen near Lexington.

One Shot and the American Revolution

The British ordered the militiamen to disperse: all but one obeyed: he fired a shot at the British troops, and with that one shot the American War of Independence was triggered (the war is also called the American Revolution). The British troops returned the single shot with a volley of fire which killed eight of the already dispersing colonists and wounded ten. From that day on, there could be no turning back for either side.

The British troops marched on to Concord the same day. News of the shootings at Lexington had however reached the militiamen at Concord, and the British troops were attacked as they started burning the supply store they had initially set out to destroy. In the second armed conflict with the militia, the British troops were routed and fled, suffering 273 casualties to the militia's 95.

Resistance Formalized

The Second Continental Congress duly convened in Philadelphia in May 1775, and declared "American" determination to resist British aggression with armed force. It also drew up measures to create an army, appointed George Washington as commander in chief; authorized the issuing of paper money and took on the role of a formal government.

The conflict was in numerical terms, uneven: England, Wales, and Scotland had a combined population of about 9 million, compared with 2.5 million in the 13 rebel colonies, nearly 20 percent of whom were Black slaves. In addition the British government counted on mobilizing thousands of loyalists in America and Native Americans who were hostile to White expansion.

Washington's main army, called the Continental Army, never had more than 24,000 active-duty troops, and was poorly supplied and always short of weapons and food. These included only about 20,000 regulars and a smaller number of militiamen (who, because of their preparedness to take up arms at a minute's notice, were given the name Minutemen).

In a bizarre turn, a number of German mercenaries from the state of Hesse-Kassel were recruited by the British and fought against the rebels. These Germans were called Hessians - despite fighting with distinction, they are best remembered for the defeat they suffered at the battle of Trenton in December 1776. Many of the Hessians settled in America and Canada after the war.

Bunker Hill

Meanwhile the British suffered two more military humiliations at the hands of the militia: buoyed by the success of Concord, the militia went onto the offensive: as part of a wider move to surround Boston, a section of the fledgling American army occupied an outpost called Breed's Hill (although they were supposed to occupy the nearby Bunker's Hill) at Charlestown, in June 1775.

British troops tried twice to dislodge the militia by storming the hill, each time being beaten back with significant losses. Finally the militiamen ran out of ammunition, and retreated: but the Battle of Bunker's Hill (as it became known) severely dented the image of the British army, and provided a great morale boost to the rebels. The British suffered more than 1000 casualties, compared to the total American losses of 140 dead and 270 wounded.

Civil War in the South

Fighting then broke out between revolutionaries and loyalists in Virginia: in June 1775, the governor of Virginia, Lord John Dunmore, took refuge on a British warship in Chesapeake Bay and from there organized two military forces: one of Whites, the Queen's Own Loyal Virginians, and one of Blacks, the Ethiopian Regiment.

In November, Dunmore issued a controversial proclamation offering freedom to slaves and indentured servants who joined the loyalist cause. In North Carolina, Governor Josiah Martin, tried to maintain his authority by raising a force of about 1500 Loyalist migrants. However, in February 1776, the Patriot militia defeated Martin's army in the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge, capturing 800 loyalists. In Charleston, South Carolina, in June 1776, revolutionary forces comprised of ordinary citizens repelled an assault by about 3000 loyalists and British troops.

The Green Mountain Boys and the American Invasion of Canada

A fort in North Eastern New York state, Fort Ticonderoga (which had been captured by the British from the French in 1759) fell in May 1775 to a rough and ready militia group from Vermont called the Green Mountain Boys - a group of dubious moral origin who had originally been set up to harass and rob British New York state officials and settlers. The capture of this fort - along with its valuable cannon - was a real military breakthrough, and the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, Ethan Allen, went on to become an American revolutionary hero.

The Americans pushed northwards: the British garrison at Crown Point on Lake Champlain surrendered and in September, an American army captured Saint Johns and then went on to Montreal, which was captured without any serious resistance. By November 1775, another American force - consisting of only just over 600 men - had advanced as far as Quebec, where it joined up with two other American armies and launched an attack on the well fortified British held city. They failed to capture the city, instead putting it under siege until April 1776, when a British relief convoy raised the siege and recaptured Montreal from the disease-ridden and poorly supplied American force.

Declaration of Independence

This setback did not discourage the rebels: on 2 July 1776, the Second Continental Congress declared independence, and on 4 July adopted a formal declaration of Independence from Britain.

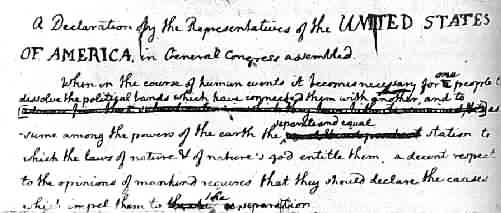

The first draft: Thomas Jefferson's first write of the Declaration of Independence, in his own handwriting.

New York City Invaded

In July 1776, a British army of more than 30,000 men landed on Staten Island near New York City and by the end of August launched an attack on the 10,000 American troops entrenched on Brooklyn Heights. The Americans, faced for the first time by a professional and experienced army of this size, were beaten: the fleeing revolutionaries were given hidings on their way out in pitched battles at Harlem Heights and at White Plains in October 1776.

George Washington, who was personally leading the Continental Army, was outnumbered, outgunned and inexperienced: his failure to evacuate the emplacement known as Fort Washington on the northern end of Manhattan Island, saw 3000 of his men being captured by the British. This persuaded Washington to leave the British to the area and retreat south.

The rebels then won battles at Princeton and Trenton in December 1776, where, to forestall a British attack on Philadelphia, Washington crossed the Delaware River with a sizable force at night and surprised the British supporting German mercenary force of 1,500 Hessians. The surprise was so absolute that the battle was over in 45 minutes, rallying Washington's army and the rebel cause after the defeat of the Canadian invasion and the occupation of New York by the British. The British however continued to use their military superiority to push onwards: in December they captured the important port of Newport, Rhode Island.

The British Capture Philadelphia

The British then advanced on Philadelphia with about 20,000 men. Although the American Congress fled the city, Washington himself had no choice but to meet the British in battle again with his badly outnumbered army. The result was predictable: winning two outflanking battles, at the Battle of the Brandywine in September, and at the Battle of Germantown in October 1776, the British easily seized the city, forcing Washington to retreat once again.

The British Strike South

In July 1777, a British army of 9000 men advanced south from Montreal and retook Fort Ticonderoga, and began to move south toward Albany. Simultaneously, a mixed force of about 2000 British regulars and Amerinds marched south along the Saint Lawrence to Lake Ontario with the aim of linking up with the British army which had just retaken Fort Ticonderoga.

They were however defeated in their attempts to break an American garrison in their path at Fort Stanwix: a large number of Amerinds then deserted and the remainder of the British force had to retreat to Montreal, their objective unachieved. Then a small American militia from New England achieved a stunning victory which was to mark the first of a number of successes for the revolutionaries: a British relief and supply column, on its way to Fort Ticonderoga was smashed in August 1777, at the Battle of Bennington.

Saratoga

By mid September, the British army in the north had pushed to outside Saratoga but were prevented from proceeding south by American troops at Bemis Heights. The British army, now reduced to around 5000 men, withdrew to Saratoga, where it was besieged by an ever increasing American force of 17,000 men. In October, the British army surrendered at Saratoga: the first major military defeat for the British.

French Intervention

The most important effect of the victory at Saratoga was the intervention of France: still seeking revenge for their defeat in North America at the hands of the British in 1763, France formally allied itself to the rebels although it had been secretly aiding them since the war began.

In 1776, a fictitious company was set up in Paris under the direction of the author Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, to funnel military supplies to the American colonists, with the purchase of these supplies being paid for by a secret loan from the French and Spanish governments.

The victory at Saratoga however now prompted bolder action, and in February 1778, the Continental Congress entered into a formal alliance with France. The French agreed to give up their claim to Canada and regions East of the Mississippi River and promised to fight until American independence had been achieved. In return, the United States opened up their trade to French merchants and agreed to support French territorial gains in the West Indies. Because of this treaty, war soon broke out between France and Britain.

Valley Forge

Despite this turn of events, Washington was barley able to hold his exhausted army together through the severe winter at the encampment of Valley Forge. There, the army of 11,000 men holed up from December 1777 to June 1778, being devastated by a harsh winter and lack of supplies.

Here 2500 soldiers died from exposure or disease in the winter encampment, while desertions cut his army down to its all time low of about 6000: Washington feared a full scale mutiny and desertion which would mean the end of the rebellion. However, a Prussian volunteer, Baron von Steuben, took command of the camp and restored discipline, remolding the American army through efficient drilling and organizational techniques.

The British Attack the South

After the defeat at Saratoga, the British then decided to secure their forces in two seaports in the north: New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. The army in Philadelphia was duly evacuated overland to New York, on the way fighting an inconclusive battle with Washington's forces at Monmouth in New Jersey in June 1778.

With their forces in the north secure, the British then concentrated on attacking the south. In December 1778, a British army of 3500 captured Savannah, Georgia, and took Augusta in the same state in January 1779. By the end of that year, most of Georgia had been captured by the British forces: in May 1780, British forces, aided by local loyalists, took Charlestown, the major port city of the next state, South Carolina. With a further victory at Camden in August 1780, the British then controlled most of South Carolina as well.

England Raided

The military victories aside, the British however suffered from an outrageously long supply line - across the Atlantic ocean - and this logistical nightmare was complicated by attacks from the small American navy which took on two forms: attacks by gunships and attacks by private ships. On two occasions a small American naval force captured the port of Nassau in the Bahamas.

The most famous American naval officer of the war was the Scottish born John Paul Jones, who started off serving in the British Navy, but deserted to the Americans after killing one of his crew in 1773. In America, he joined the fledgling American navy, taking command of a number of raider ships with which he twice carried the war into British waters: in 1778, he actually raided England itself, attacking the port of Whitehaven; he also won renown for capturing a British sloop, the Drake, off the British coast.

The Privateers

The Americans did not possess a navy the size of Britain's: the American government then gave commissions to about 450 private American ships, with instructions to attack any English ship they came across: these privateers, as they became known, eventually captured or destroyed nearly 2000 British merchant ships.

Guerrilla War

American resistance in the south slowly picked up: bands of guerrillas attacked the British supply lines continuously - eventually the safety of the transport convoys became so tenuous that the British retreated into the large port towns of Savannah and Charlestown rather than sit as isolated targets in the interior.

A series of important American victories then followed; at Kings Mountain in October 1780; at Cowpens in South Carolina in January 1781; and at Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina in March 1781. The British started moving the main body of their army north to Virginia. The remaining British troops in South Carolina fought several successful rearguard actions against the Americans, but could not deliver a single decisive defeat as the American guerrillas melted away into the countryside each time a serious defeat seemed imminent.

British Defeat at Yorktown

In July 1780, a French army of 5000 men invaded Newport and ejected the British: the presence of this French army gave Washington enough military strength to attack the British army which had been moving north through Virginia, and which was now holed up in Yorktown. A French fleet then blockaded the port, preventing the British from either being evacuated or supplied: on land Washington drew up his forces and laid siege to the British force.

So it was that by September 1781, the 7000 strong British force in Yorktown was faced down by a combined land force of French and American troops of over 16,000. With no hope of resupply, the end was inevitable: the British surrendered on 19 October 1781.

Britain had been dragged into a war of her own making which she could ultimately not win: faced with an enemy spread out over a vast territory, there was no center which the British could take which would destroy the rebellion. It was therefore never possible to deliver any single knockout blow. Stripped of allies, simultaneously fighting in the West Indies, America, the North Atlantic, Africa and India, against a range of some times co-ordinated enemies who included France and its allies - Spain and the Netherlands - Britain was over stretched and was forced to concede defeat after the reverse at Yorktown.

Treaty of Paris

All sides signed the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which granted official independence to the thirteen colonies on the east coast of America: the United States of America had been born after a eight year long war.

Constitution

Having won independence from Britain, the next problem facing the Americans was to devise a constitution which would bind the thirteen ex colonies into a cohesive political whole. This would prove to be no easy task, as the very nature of the colonies as they had developed since their founding had been based on individualism and their own forms of government.

During the War of Independence, the states had been governed by an unelected congress, which had taken certain powers to itself, such as raising an army, borrowing money from foreign governments and entering into alliances against Britain. These powers codified shortly after independence, in an agreement known as the Articles of Confederation, which were in turn ratified by each state in turn.

The states generally opposed the idea of a central government, and wanted to withhold from any union the right of a central government to interfere with certain state's rights, as they became known. Initially this was agreed, but when some states started adjusting their currency levels and taxation levels to the detriment of other states and to some of their own citizens (which led to a short lived second rebellion being led by an American army veteran, Captain Daniel Shays in Massachusetts - this was put down in short order).

The Shays rebellion however convinced many that there could be no national security or stability without a central government. So it was that a meeting of specially appointed delegates from the colonies met in Philadelphia from May to September 1787, and drew up the constitution of the United States of America.

The Constitution became the law of the land in 1788, and on 30 April of that year, George Washington, who had been unanimously elected the first president of the United States, was inaugurated in New York City, the then capital. The United States of America had been born.

George Washington, first president of the United States of America.

War of 1812

The American Revolution was however not to be the last conflict with Britain: a new war broke out within 30 years. By 1812, tensions with Britain had still not died down: a series of boycotts of British goods followed the Royal Navy harassing American merchant ships on the pretext of searching for naval deserters - but were obviously designed to prevent America joining the European war on the Frenchman Napoleon's side.

What however finally provoked the US Congress into acting was proof that the British, who still held on to Canada and claimed then still largely unexplored territories on the Western seaboard, had given active aid to an Amerind tribe, the Shawnee, in an effort to resist American territorial expansion to the west. In June 1812, the US congress declared war on Britain and American forces invaded British North America - Canada - at points between Detroit and Montreal, but the plan went awry almost immediately.

Detroit Captured

The British, acting in partnership with their Amerind tribe allies, the Shawnee, launched a counter attack and captured Detroit, while on the Niagara peninsula two American armies were defeated, all in the opening months of the conflict. In 1813, American forces managed to retake Detroit after the British fleet on Lake Erie had been seized.

Finally the Americans were able to exact some victories: York (now called Toronto) was captured and a combined British and Shawnee army was defeated at the battle of the Thames in October 1813.

Creek Amerinds Attack

In 1813, the war spread to the southwest when the Creek Amerind tribe seized the opportunity to attack the White states: an American army under Andrew Jackson however inflicted a crushing defeat on the Creeks at the battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, effectively taking them out of the war.

Washington DC Burned

In July 1814, American forces fought British armies to a standstill at Chippewa and Lundy's Lane, near Niagara. Napoleon's defeat in Europe, however, freed Britain to send more troops to North America and soon the Americans faced renewed British land and sea invasions at Lake Champlain and in Chesapeake Bay. British troops then pushed south and occupied Washington DC, burning it to the ground in August 1814, just failing to do the same to the city of Baltimore in Maryland.

It was during the British bombardment of Baltimore that the American poet, Francis Scott Key, wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner" which later became the American national anthem. A renewed American offensive relieved Maryland and retook the ruins of Washington, and then both sides opened negotiations to end the war.

Sneak Attack

A treaty ending the war and restoring the border of America and British North America to what they were before the war started, was signed at Ghent, in Belgium on 24 December 1814. This treaty was signed by Britain on 28 December 1814: but then a British army launched a sneak invasion at the mouth of the Mississippi River on 8 January 1815.

The American general, Andrew Jackson, rushed south with an army and defeated the British near New Orleans. A period of diplomatic embarrassment then followed for Britain: finally the American government ratified the peace treaty on 16 February 1815, and the war came to an official end.

Racial Consequences of the American Wars with Britain

For the White population, the war of independence was psychologically testing: of the approximately 400,000 adult white men who lived in the colonies in 1775, about 175,000 fought in the war, either a rebels or loyalists. Thus, husbands or sons from nearly half of all white families were part of the "shooting" war.

The American revolution also carried with it clear racial undertones, not only in terms of the Amerinds. The open call by the British to Black slaves to rebel against the White Americans, and the raising and arming of all-Black armies for this purpose, served to alienate Blacks from the new republic: many thousands crossed into British North America with loyalist supporters to escape the slave owning Americans whose republic they feared and distrusted.

Black Slaves

The population growth in the American colonies was staggering: in 1700, there were around 250,000 people in the 13 colonies: by 1775 there were 2,5 million, a ten fold increase - of whom 567,000 - or 20 per cent - were Black slaves.

About 250,000 Blacks had been brought into North America before 1775, but the total Black population numbered 567,000 on the eve of independence. Whatever else slavery may have done to the Blacks, it certainly did not kill them, as this population growth was virtually exclusively the result of natural reproduction.

The contrast with the situation in Portugal immediately springs to mind: in that European country only about ten percent of the population was Black, yet in America at its very founding, the figure was already 20 percent: why did Portugal vanish as a world power and America then go on to become a great world power?

The answer lies in the level of integration: in Portugal there was absolutely no segregation and mixed race unions were positively encouraged: in America, not only did the huge degree of racial alienation, as outlined above, exist, but as a result integration was actively discouraged and in many states, made punishable with prison sentences (many of these anti -miscegenation laws were only repealed in the 1960s).

Thus although America always had a larger Black population, it never absorbed this population into its mainstream society, as the Portuguese did: and the difference is marked, once again proving the reality that the nature of a society is determined by the nature, or make-up, of the people dominating that society.

Amerinds

The most important consequence of the 1812 war was the breaking of the Shawnee and Creek Amerinds: from then on they were unable to resist the further White American advances across the American continent. This would have major repercussions in the next phase of American history which would see that country more than triple its geographic size and extend all the way to the Pacific coastline, swallowing up what were previously the exclusive ranges of the nomadic Amerind people.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.