MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

Chapter Fifty Three

"Our White men cutting one another's throats" - The American Civil War

When Abraham Lincoln uttered the words "our White men are cutting one another's throats" to a deputation of Blacks at the seat of government in Washington D.C. in 1862, even he could not have foreseen the slaughter that would take place over the next three years in his country: more Americans were to die in that Civil War than what were ever to be killed in any war before or ever since.

Once the Union had been established, it faced two critical issues: whether the United States of America should be a federation or a confederation; and whether the institution of indentured labor - in effect a lighter form of slavery - should be allowed to continue or not.

Together these two issues led to the American Civil War, which can be counted as one of the great turning points in American history: it set the new nation against itself, the South, supporting confederalism and indentured labor; against the North, who favored federalism and the abolition of slavery. Great White armies fought each other and finally decimated the south, all in an argument over the future of the Black race.

Growth in Territory

The United States of America soon started expanding after the War of Independence with Britain. Territories to the west of the original 13 colonies, which all lay on the eastern seaboard of continent, had in the interim been steadily filling up with Whites.

In 1791, Vermont, a frontier region settled chiefly by New Englanders, became a state; this was followed by Kentucky in 1792, Tennessee in 1796, and Ohio in 1803. Under the president Thomas Jefferson, the Louisiana territory, a vast tract of land encompassing the lands between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, was acquired for the United States. Originally ceded by France to Spain in 1762, after the French and Indian War, the territory been given back to France in 1800. The new French leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, who was obviously short of cash for his government, offered to sell the territory to the new American government for $15 million - a bargain that Jefferson snapped up, in an instant doubling the size of the United States.

Fourteen states were wholly or partly created out of the Louisiana territory alone. In 1810, the United States forcibly annexed (from Spain), the territory called West Mexico: a strip of land along the Gulf of Mexico extending westward from East Florida to the mouth of the Mississippi River. Weakened at home and in her colonies, Spain then ceded to the United States the remaining part of her North American possessions, called East Mexico, and now called Florida, in 1819.

Westward Migration

A second wave of White westward migration took place in the aftermath of the economic hardship on the eastern seaboard which followed the war with Britain in 1812: Whites poured into Louisiana and a state was officially declared there in 1812. Indiana followed in 1816, Mississippi in 1817, Illinois in 1818 and Alabama in 1819.

Life in these frontier territories was dangerous and difficult. The settlers were faced not only with the problems of clearing land and building stable communities, but were also continually subjected to attacks by Amerinds. In the face of all the problems the frontiersmen became hardy and daring: a belief in what was called manifest destiny and idealism took hold, propelling the settlers on where others might have given up.

Cotton Industry

In the southern states the economy became more and more centered on the growing of cotton, using a labor intensive Black slave population. The South grew wealthy on this cotton based economy: great towns and cities were built which rivaled those built on the original eastern seaboard. Many southerners lived lives of near aristocratic level.

But underneath the facade a time bomb was ticking: the interlinked issues of Black slavery and the right of the central government to interfere in the right of states to regulate this practice (and other laws) had not gone away: indeed with the passage of time they came to dominate the political debate. In contrast to the agriculturally based south, the north east was marked by rapid industrialization: caused partly by the emigration of farmers to more fertile lands in the south and west; but also driven on by economic necessity as a result of the economic hardship which followed the British - American war of 1812.

The north also had a larger population than the south: a factor which ultimately caused the American congress to weigh heavily in favor of bringing in protective tariffs for northern industry. The introduction of tariffs protecting northern industry were opposed by the south for two reasons: firstly it illustrated the problems with federalism: because the northern states had a larger population, they had a majority in congress; and secondly, with virtually no major industrial capacity of its own, the south objected to being forced to gratuitously pay higher prices for northern industrial goods.

Slavery

As the American constitution recognized slavery and most of the signatories to the constitution themselves owned slaves, nothing was done to either end the practice of slave owning or encourage it. This ambiguous state of affairs resulted in some states allowing slavery and others forbidding the practice.

By the end of the 18th century, all the states north of Maryland, except New Jersey, had provided for the abolition of slavery. Caught in a web of indecision, the US Congress sometimes acted for, and sometimes against slavery: an Ordinance in 1787, prohibited slavery in the northwest territory; but in 1793, it passed the Fugitive Slave Law, which permitted a slave owner to reclaim escaped slaves from anywhere in the United States - upon production of "proof of ownership."

At differing times from 1791 onwards, the union admitted states which had legalized slavery and those who did not. Slave owning states accepted into union included Kentucky, Tennessee, and Louisiana; non slave owning states included Vermont, Ohio and Maine. In 1808, sensing that the Black population was already growing, the US congress passed a law forbidding the further importation of Blacks into the country: it did not however abolish slavery itself.

The Missouri Compromise

It was only when the state of Missouri applied for membership of the Union in 1818, that the issue became hotly debated: representatives from those states in Congress who had abolished slavery, expressed concern that the admission of a slave owning state into the union from beyond the west of the Mississippi River would create a precedent for the future admission of slave owning states from the western territories into the union.

A law called the Missouri Compromise resulted, in terms of which Missouri itself was admitted to the union, but slavery was prohibited in all other states to be created out of territory purchased from France (called the Louisiana Purchase).

After the passing of the Missouri Compromises, the anti-slavery activists in the north began to organize politically against the practice. In reaction, the south, arguing that the very basis of their labor intensive cotton industry was threatened, passed stringent laws to keep its slaves under control. In 1840, southern pressure on congress caused the passing of the so-called gag resolution, which prevented Congress from considering any further petition presented to it on the subject of slavery.

The debate over slavery then intensified, with the US Congress very often being split down the middle over the issue. Just as it seemed the issue was coming to a head, the attention of the nation was diverted by the outbreak of a new race war in the south: that with Mexico which erupted over the territory of Texas.

The successful conclusion of the war with Mexico saw even more territories added to the union: Texas, Arizona, California, New Mexico and Oregon. The addition of these territories once again brought the debate on slavery to the fore.

As before, the Congress vacillated and always tried to put the unity of the country first by trying out any number of compromises. In this way California was admitted to the union as a non slave owning state: while the territories to the east of California (Arizona and New Mexico) were to be left to decide on their own on the issue.

The Underground Railroad

Then congress passed a new fugitive slave law in 1850, which made much more effective the measures that could be taken by a slave owner to reclaim an escaped slave. Together with the laws allowing the "right to decide" on slavery for the new western territories, these contradictory laws became known as the Compromise Measures.

However, many anti-slavery activists in the north refused to obey the rules laid down in the fugitive slave laws and actively helped escaped slaves travel to Canada through secret routes known as the Underground Railroad.

In 1854, the issue of the dual attitude towards slavery flared up once again with the passage of a law repealing parts of the Missouri Compromise. As part of a new law dividing the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase into two further states, Nebraksa and Kansas, it was decided that the territories' inhabitants could decide for themselves whether they wanted slavery or not.

Anti slavery activists saw in this law the institution of slavery being extended north from the original boundary established by the Missouri Compromise and increased their agitation against slavery and the fugitive slave laws.

The act also brought about violent conflict in Kansas between abolitionist settlers who had emigrated from New England for the purpose of making Kansas a free state, and pro-slavery forces who invaded Kansas from the neighboring slave state of Missouri to vote in favor of slavery.

The pro-slavery forces sacked and burned the anti-slavery town of Lawrence in May 1856, and in retaliation, John Brown, a fanatical abolitionist, led a group which killed five pro-slavery adherents at Pottawatomie Creek.

In 1857, the US Supreme Court gave a judgment in the famous Dred Scott effectively sanctioning slavery when it declared that Black slaves were "property and not citizens" and that Congress had no right to prohibit slavery.

Against this backdrop - with the US Congress being torn between pro and anti-slavery factions, and with the very principle of the union being torn apart by divisions over the right of the central government to interfere in individual state's laws or not - the scene was set for the devastating civil war in America.

Secession and War

The election victory of a northern Republican Party presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, in 1859, proved to many Southerners that the commanding position in national affairs now belonged to the North, and that it seemed that all major decisions regarding social and economic matters would henceforth be taken by the North and imposed on the South.

Interestingly enough Lincoln himself initially advocated state control of slavery, not outright abolition.

Then a southern state took the momentous decision to withdraw from the union. On 20 December 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union and a few days later its state troopers laid siege to the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston. Within a month the states of Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, and Georgia had officially withdrawn from the union, to be followed a short while later by Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

The Confederate States of America

On 4 February 1861, delegates from six of the seceding states met at Montgomery, Alabama, and formed a provisional government called the Confederate States of America - an indication of the government form they preferred (a confederation having a much looser central government than a federation).

On 8 February, they adopted a confederal constitution and the next day elected a provisional president and vice president; Jefferson Davis and Alexander H. Stephens respectively. They were elected unopposed in a formal election held in 1862.

Seeing his country fall apart, president Lincoln tried hard to prevent a conflict: in his inaugural address as president on 4 March 1861, he made his position clear: He did not intend to interfere with slavery in the states where it existed; at the same time, he declared that no state had the right to leave the Union as and when it pleased.

The First Shots

Then events moved with surprising speed: on 12 April, the South Carolina troopers who had been peacefully besieging the garrison of Fort Sumter in Charleston all the while, began a cannon bombardment of the building. The Union troops surrendered two days later. Faced with armed rebellion, Lincoln's hand was forced: on 15 April, he called upon the loyal states for 75,000 volunteers to defend the Union, but the southern states which had not yet thrown in their lot with the rebels in the deep south refused to send troops: they too joined the confederacy.

Black Troops

Before the Civil War, Blacks were not allowed to join state militias or the U.S. Army or Navy, and the federal government refused to give passports to free Blacks. This status had been confirmed by the US Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case of 1857, when it had ruled that Blacks could never be citizens of the United States.

When the Civil War started, the northern government initially refused to allow Blacks to be enlisted into the army. By 1862, however the rules had been changed slightly: Blacks were allowed to enlist in segregated units, led by White officers. By the end of the war, more than 200,000 Blacks had served in the Northern Army and Navy.

Differing Aims

The North and the South had differing aims in the war, which were to determine their strategies: the South only wanted to maintain its independence; while the North wanted to suppress the secession. This meant that the North would have to invade the South: this led to the North being the offensive power in the war, with the South being the defensive power.

First Battle of Bull Run

The first major engagement of the war occurred in 16 July 1861, when a Northern (or Union) army advanced south against a Southern (or Confederate) army which had taken up position about 40 kilometers (25 miles) south west of the capital, Washington, DC. Finally engaging battle on 21 July, the struggle appeared initially to go well for the Union army.

The Confederates were surrounded and only held together by the personal heroism of their commanding officer, general Thomas Jackson, who won the name "stonewall" for his refusal to give way or surrender (a phrase which has entered the English language with that meaning).

Then Confederate reinforcements arrived and the Union armies suffered a major defeat, fleeing in chaos towards Washington. The defeat stunned the North: it had been presumed that the conflict would be a short and sharp affair, as the North was in theory the overwhelming power, having not only all the major industrial power but a population of over 22 million against the South's total of less than nine million.

Mini Civil War in Missouri

In May 1861, a mini civil war of its own broke out in the state of Missouri, with pro-confederates and pro-unionists taking up arms against each other in a bloody fratricidal strife which was never fully resolved. In August, a large pro-Union army invaded the state, and although they defeated a Confederate force at the Battle of Wilson's Creek in southwestern Missouri, the state continued to be torn apart by armed militia supporting the opposing sides.

Kentucky

The state of Kentucky had remained neutral: but by the time that the war had been raging for several months, this neutrality was ignored. In September 1861 the Confederates occupied the city of Columbus and that state's legislature formally asked the Union government for help. A Union force under the famous Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, moved into Kentucky and engaged the Confederates at the Battle of Belmont, which ended indecisively.

Sea Invasion

The North then achieved an important breakthrough: a sea borne invasion of the South Carolina coast saw a number of important forts along the southern coastline falling into Union hands, establishing a base for further operations inland. In November 1861, the Union general, Thomas Sherman, landed with a force of 12,000 men on the coast, almost without opposition.

Near War with Britain

The Confederacy then sent two "commissioners" - ambassadors by any other name - to France and Britain to try and drum up support. The two men ran a Northern naval blockade to get to Havana in Cuba. Then, on 7 November 1861, they left Cuba on the British ship Trent. The next day, Captain Charles Wilkes of the U.S. vessel San Jacinto, stopped the Trent, searched it, and took the two Confederate representatives on board his own ship and later to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor.

By arresting the Confederates on board a neutral ship, the Union had however clearly violated a well established principle of international law of the inviolability of neutral powers. Indeed, the US Congress had gone to war with Britain only some 50 years previously, in the 1812 war, over this very issue when British ships had seized American ships sailing to France.

For a while it seemed as if Britain would enter the war against the Union: only an apology by the Union government and the release of the Confederate Commissioners to continue their journey served to avoid the direct involvement of Britain in the war, which would have been a serious blow to the Union.

As it was, the precedent had been set: from then on Britain would openly favor the Confederates, even allowing Confederate warships to be built on the British shipyards. Finally the links between Britain and the Confederacy were cemented by the personal friendship of the British Jewish prime minister of the time, Benjamin Disraeli, and the Confederate Jewish Secretary of State, Benjamin Judah. Disraeli's views on race (discussed in an earlier chapter) made him personally sympathetic to the Confederate cause. When Judah was forced to flee the South at the end of the war, he stayed as Disraeli's personal guest at the latter's private house in England.

The Union Strikes South

In January 1862, the Union finally launched its first major invasion south: an army under Ulysses Grant advanced on two forts held by Confederates, Fort Henry and Fort Doneslon. Both were taken after a short engagement and siege, the first major Union victory of the war. These victories were followed up by a further victory over a Confederate force at the Battle of Pea Ridge, also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, in Arkansas, in early March 1862.

Battle of Shiloh

On 6 April 1862, a Confederate army, which had managed to creep up on Grant's army undetected, launched a surprise attack on the Union camp at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. The battle, which became known as the Battle of Shiloh, saw two days of savage fighting, ending in the defeat of the Confederate attackers.

Losses were however staggering: 13,000 out of more than 62,000 Unionists and 10,700 out of 40,000 Confederates. The scale of the losses - with four times as many Americans dying in the one battle as had died in the entire American war of Independence, shocked all sides.

First Ironclad Engagement

Both the Union and Confederates possessed some of the latest technology available: including the innovative ironclads, or iron ships, which were to revolutionize naval warfare. Early in March 1862 the Confederate ironclad, the CSS Virginia (also known as the Merrimack), entered the mouth of the James River in Virginia, attacking a number of wooden Union ships enforcing a blockade of the state's major seaport. The Virginia was impervious to the fire of the wooden ships, and sank one and ran another three aground in quick succession.

The Union forces were soundly beaten, but the next day a Union ironclad, the USS Monitor, arrived in the area and engaged the Virginia - the first ironclad naval clash in the world. They fired shells at each other for hours, often hitting but never doing any damage. Finally, their crews exhausted, they called it a draw.

The Shenandoah Campaign

The Union then set as its objective the capture of the capital city of the Confederacy, Richmond in Virginia. However, the Confederate general "Stonewall" Jackson was operating with a relatively small army of 16,000 men in the Shenandoah Valley, just to the south of Washington D.C..

When the Union attack on Richmond started, Stonewall received orders to prevent the Union from sending reinforcements to the Union army in the south. Jackson then opened a remarkable campaign, deceiving the Unionists into believing he had a huge army. By mobility and inventiveness, Jackson won victories in the valley at McDowell, Front Royal, Winchester, Cross Keys, and Port Republic before withdrawing to help in the defense of Richmond. Jackson's tactics succeeded; to oppose him and the 16,000 men who fought with him for most of the campaign, the North deployed an army of 55,000 men, sorely needed elsewhere.

Richmond Attacked

The Union drive on Richmond then took place, starting with the landing of a 100,000 strong Union army in April 1862, which then took Yorktown after a month long siege. Advancing on Richmond, the Union forces were met in battle by a Confederate force at Fair Oaks, only 10 kilometers from Richmond. The Confederates were defeated, but the advance on Richmond ground to a halt as well.

After this battle, the Confederate general Robert E. Lee, was appointed commander of the Confederate army of Northern Virginia. Lee soon became an idolized figure in the south, with his outstanding ability as a military commander and strategist combined with his personality often being the only thing which kept the entire South from crumbling.

Seven Day's Battle

From 25 June to 1 July 1862, a series of running battles took place between the Union and Confederate forces, known as the Seven Day's Battle. On the second day, the Unionists drove back a Confederate attack north of Richmond, but failed to follow up on the victory by advancing to Richmond, only eight kilometers away.

A Union force falling back to a place called Gaines' Mill was subsequently attacked by a Confederate army and was defeated: the Confederates managed to seize the initiative and the Union drive on Richmond was turned back. The attempt to capture Richmond exacted a heavy toll: 16,000 Union casualties, and 20,000 Confederate casualties, one fifth of Lee's army.

Capture of New Orleans

In the deep south however, the Unionists made good their defeat in the north: in April 1862, a combined Union naval and infantry force of 18,000 men advanced up the Mississippi River. The Confederates launched desperate efforts to stop the naval advance, laying chain cables across the river and then setting fire rafts adrift into the midst of the Unionist fleet.

The Union force managed to evade all these hindrances and reached New Orleans, the capital of Louisiana on 25 April 1862. The massively outnumbered Confederate defenders in the city - some 3,000 men - then fled, leaving the city open to be occupied by the Unionists. For the rest of the war, New Orleans, the biggest Confederate city and the key to the Mississippi, remained in Union hands. Its loss was a disaster for the Confederacy.

Confederate Victory in the North

Even though New Orleans had fallen, in the north, the Confederate army was to achieve one of its major victories: on 9 August, Robert E. Lee attacked one of two Union armies attempting to link up, at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, near Culpeper, Virginia, and crushed them.

Following up on this victory, Lee swooped on a Unionist army base at Manassas Junction, capturing a significant quantity of much needed supplies. Lee then drew up a defensive line in anticipation of a renewed Union assault. Lee did not have to wait for long: on 29 August, a Union army of 62,000 men attacked the Confederate force of around 23,000.

"Stonewall" had however not earned his nickname for nothing, and by a clever defensive strategy managed to withstand the overwhelming assault, creating such confusion in Union ranks that the Union commander thought the battle had been won, and sent a telegram to Washington D.C. announcing that the Confederates had been beaten.

It was a premature telegram: within hours a Confederate artillery unit had reinforced Lee and the resultant bombardment decimated the Union force. The Northerners fled in utter defeat, pursued by the victorious Confederate troops. Nonetheless the Confederate victory had been dearly bought: although the Unionists lost 14,500 men to the Confederate's 9,200, the South could not afford endless losses on this scale, as the North had larger reserves upon which to draw.

The South Overreaches Itself: The Battle of Antietam

Flushed with the impressive victory, the South decided to go onto the offensive and move the theater of the war out of Virginia into Union territory. The Confederates then invaded Maryland itself. This turned out to be a major miscalculation: although the Confederates were successful in their initial objective of capturing Harpers' Ferry in Maryland, the Confederate force of 35,000 was finally faced by a Union army of 75,000 men.

The Battle of Antietam followed in September 1862: outnumbered, the Confederates barely managed to hold off a Union attack, and were forced to retreat step by step back into Virginia. Not only was the invasion of Maryland a military defeat for the Confederates, but the Battle of Antietam became the bloodiest one day battle of the Civil War and indeed of all American history: the Union casualties were about 12,500 and Confederate casualties about 10,500.

The Battle of Perryville

By August 1862, the neutral state of Kentucky had been invaded by both Confederate and Unionist armies; the population itself had broken up into pro-Union and pro-Confederate camps. The Northern and Southern forces fought a large but indecisive battle in October 1862, the Battle of Perryville: it was only a union victory in as much that the Confederate forces withdrew south after the battle itself, but this retreat was not followed by a Union advance.

Union Defeat at Fredericksburg

Determined to try and advance somewhere, the Unionists then launched a full scale assault on the Confederate army in Northern Virginia, who had dug themselves into a well planned string of defensive positions around the hills near Fredericksburg in Virginia. On 13 December a huge Union army stormed the Confederate positions at Fredericksburg: the Confederate defenses were far too good, and the result was a slaughter. Union losses in killed, wounded, and missing amounted to 12,600, as opposed to Confederate losses of 5,300.

Murfreesboro

In Tennessee, the anarchy continued, punctuated only by a bloody battle between the opposing armies at Murfreesboro on the last day of the year 1862, southeast of Nashville. After three days of fighting, in which the two armies lost nearly 25,000 of the 76,000 men engaged, the Confederates withdrew, leaving the Union army equally shattered and unable to pursue the Southerners.

The Union Attempt to Split the Confederacy

The Union armies then developed a strategy which entailed advancing down the Mississippi River from the North and thereby splitting the confederacy in two. For this purpose two large army groups were assembled, with the first aim of capturing the important Confederate town fortress of Vicksburg. The Union advance was cut to ribbons in December 1862, at the Battle of Chickasaw Bluffs. The first Union attempt to cut the South in two failed dismally.

The Grierson Commando

In April 1863, one of the most audacious engagements of the entire war was successfully completed by a Union cavalry detachment under the command of Benjamin H. Grierson. Leading a force of 1700 men, Grierson's force left La Grange, Tennessee, in April 1863. Sixteen days later, after covering 966 kilometers (or 600 miles), he reached Baton Rouge, Louisiana. On the way he destroyed miles of railroad, took 500 prisoners, and eluded thousands of Confederate troops sent against him, losing only 24 men along the way.

The Second Drive on Richmond

The Unionists then relaunched a drive on Richmond: an army totaling 134,000 well-equipped men set out for what the North hoped would be a knock out blow of the Confederate forces in Virginia. "Stonewall" Jackson met the main thrust of the Union assault in May 1863, taking two days to defeat the numerically superior Northerners once again, with the assault on Richmond collapsing for the second time.

During this battle, know as the Battle of Chancellorville, "Stonewall" Jackson was accidentally killed by fire from his own Confederate troops: the loss of this ablest of all American generals was a grievous blow for the Southern war machine.

The Union defeat had however once again exacted a disproportionally heavy toll from the Southerners: 17,300 Union causalities as against 12,750 Confederate casualties. Percentage wise, this was a far greater blow to the Southern armies; slowly but surely the tide of the war started to turn.

Fall of Vicksburg

In April, the Unionists relaunched their attempts to take the Mississippi River valley. Despite suffering heavy losses, the Union Commander Ulysses Grant managed to push south to Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, with an army of 44,000 men, where they quickly overwhelmed the 6,000 Confederate defenders in a short battle on 12 May 1863.

Grant then advanced on Vicksburg once again, defeating two advance assaults by the Confederate army defending the city. Finally, after two failed and extremely costly assaults on the city itself, Grant decided to lay siege to the city rather than wear his forces out trying to capture the fortress.

The siege lasted six weeks, with the Confederates finally surrendering the city on 4 July 1863. The Confederacy was cut into two and the South was dealt a near fatal blow: after the fall of Vicksburg, an outright military victory by the South no longer became a realistic option.

Gettysburg

In the light of the rapidly deteriorating military situation, the South tried to play an all or nothing campaign: Lee pushed north to Pennsylvania, hoping to inflict a decisive victory on Union soil. On 1 July 1863, the Confederate and Union forces met in battle at the little town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Initially the Union troops managed to ward off a determined Confederate assault; the Confederate attacks continued over the next two days, with huge losses being inflicted on all sides. Finally, outnumbered, under supplied and having taken massive casualties, the Confederates were forced to retreat.

The battle was a decisive Union victory, even though a quarter of all the men who took part in the battle fell: the Northerners suffered about 23,000 casualties to the Southerners 25,000. The Union force was too devastated to pursue the Confederates.

In November 1863, Lincoln dedicated a national cemetery to those who had died in the Battle of Gettysburg. His speech, known as the Gettysburg Address, became famous as an expression of the principles for which the North claimed to be fighting, and reaffirmed his determination to see the country reunited.

Lincoln Suspends Democracy

Although the North had won two of the most important engagements of the war to date, at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, anti-war sentiment had grown in the North to the point where open rebellion broke out. A great number of Whites in the North, as Lincoln had correctly predicted, did not care one way or the other on the issue of slavery, and many became weary of war which seemed to be dragging on indefinitely.

Also, the decision by Lincoln to rule autocratically as a result of the rigors of the war, greatly upset many in the North, who questioned his behavior in the light of the very democratic principles for which he claimed to be fighting. Lincoln indeed had suspended many of the tenements of democracy: critics of the war were arrested and detained without trial for long periods.

The most famous example was an anti-war congressmen from Ohio, Clement L. Vallandigham, who was arrested in May 1863 after making an anti-war speech. A military court sentenced him to prison, but Lincoln changed the penalty to banishment to the Confederacy.

Then on 1 June 1863, Lincoln suspended the principle of freedom of speech - a right guaranteed by the first amendment to the constitution - by banning publication of the Chicago Times, which had become increasingly anti-Lincoln. An uproar followed, and Lincoln was forced to back down on the issue.

Anti-Black Riot in New York City

Then in 1863, the Union government launched a forced conscription campaign - the first in the North - in New York City. A mob, made up mostly of foreign-born laborers, chiefly Irish-Americans, attacked and burned the draft headquarters and other government offices. For four days, the mob fought off police, firemen, and the local militia. Blacks were targeted by the White mob as the primary cause of the conflict in the first place, and attacks took place at random on any passing Nonwhites.

The Union government was forced to divert a part of the army facing the Confederates in Virginia back to New York City to restore order. Similar disturbances took place in other parts of the Union, although not on the same scale as in New York City.

Chickamauga

By this stage of the war, countless localized clashes were taking place on a daily basis up and down the entire length of the front, which now extended over several states running from the eastern seaboard to the Gulf of Mexico. In September, a Union force launched a major drive against the important Confederate rail center of Chattanooga in Tennessee.

The Confederates withdrew from the city, preferring to make a stand outside, at Chickamauga. After very nearly being defeated by a clever Confederate defense, the Unionists won the Battle at Chickamauga, which was notable for the Union Commander giving up halfway through and personally fleeing to Chattanooga. The military situation for the Northerners was only saved by one of his officers fighting off the final Confederate assault.

The battle then ended in a stalemate, and the Union troops then followed their commander back into Chattanooga. The Confederates managed to lay siege to the Union forces in that town, but were ultimately driven off in two famous battles, at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, both outside the city. In battles lasting three days, the Unionists achieved the incredible feat of dislodging the Confederates from their well fortified positions; the region fell under complete Union control by the end of the year.

The Wilderness

In May 1864, the Southern and Northern armies once again engaged each other in the thick woods of the Wilderness, Virginia, close to the old battlefields of Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg. In fierce fighting which was marked by great confusion, neither side managed to inflict a decisive defeat upon the other, but losses were heavy: about 18,000 on the Union side and about 11,000 for the Confederates.

The South was slowly bleeding dry, by the time of the great assault on the South of that year, the Union army taking part in that campaign numbered some 235,000 men. Against this the Confederates could only put 135,000 under supplied and underfed men into the field.

Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor

In the interim, Ulysses Grant had been appointed commander in chief of the Northern forces. Disregarding the losses in the Wilderness, Grant ordered the union army to press home an attack, the first time the Northern army had done so after such a major battle.

The Union army pushed south and in May, a ten day battle erupted in the small town of Spotsylvania Courthouse, Virginia. Once again the losses on the Union side were enormous: another 17,000 casualties. Ordering his army on, Grant then pushed on to try and seize Richmond once again. The Confederate army, under the command of Robert E, Lee, drew together its reserves and met the Union charge head on at Cold Harbor, Virginia, within sight of Richmond.

The Battle of Cold Harbor followed: it was a major defeat for the Union side, who lost more than 7,000 men against the Confederate losses of less than 1,500.

Petersburg

Having failed to take Richmond once again, the Unionists then tried to attack the Confederate capital from the south, and launched an encircling movement, striking south before turning north and attacking Richmond before the Confederates could swing their army round.

The plan nearly worked, with the Confederates only becoming aware of the troop movements at the very last moment. The Union advance was halted at the town of Petersburg, south of Richmond, by a desperate rearguard Confederate action: the town was placed under siege, which lasted for more than a year.

Sinking of the Alabama

The failure to take Richmond for the third time caused great depression in the Union, only tempered by the news of the naval victory off the coast of Europe. The Confederate ironclad, the CSS Alabama, one of the ships the British had built especially for the South, had played havoc on the Union's trade and supply routes to Europe, sinking dozens of Union ships and capturing many prisoners. In June 1864, the Alabama landed at Cherbourg in France for repairs and to off load its prisoners. Outside the Harbor, waiting for the Alabama to come out, was the USS Kersarge, and the two ships engaged on 19 June 1864.

The battle was short and sharp: the CSS Alabama was sunk in less than two hours. The CSS Florida, second among the great Confederate raiders, was captured in violation of international law in the Harbor at Bahia (now Salvador), Brazil, in October 1864.

The CSS Shenandoah, which had been taking prize vessels, chiefly whalers, in the Pacific, did not learn that the war was over until 2 August 1865. It succeeded in making its way to Liverpool, England, in November 1865, and there its captain turned it over to the English authorities.

The North Advances Into Georgia

In June 1864, the Union forces launched a major invasion of the state of Georgia, advancing 129 kilometers (80 miles) in a month, each time forcing the Confederate defenders to fall back without a major engagement taking place.

The First Assault on Atlanta

Finally in July 1864, the Union forces stormed a strong confederate defensive line on Kennesaw Mountain. Once again the defensive tactics of the Southerners won the day: the Union forces were defeated, losing 2000 killed and wounded, to the Confederate's 500. Nonetheless, the Unionists kept pushing south: by July they had reached the outskirts of Atlanta, the capital of Georgia.

The Confederates put up a desperate resistance with their massively outnumbered army: by the end of July the Unionists had lost 9,000 men in the outskirts of Atlanta, while the Confederates had lost 10,000 wounded, killed or captured. At that rate of attrition, the Confederate collapse was only a matter of time.

The Confederate's last Throw: the Attempt on Washington, D.C.

While Atlanta and Petersburg were under siege, the Confederates launched a desperate move to force a change in the direction of the war. A Confederate force under the command of General Jubal A. Early, launched a daring raid deep into Union territory, coming to within sight of the capital, Washington D.C., sparking off widespread panic in that city on 11 July 1864. The Unionists had however managed to draw up a considerable defensive army around their capital. Realizing that an attack on the city would be futile, Early withdrew.

Fall of Mobile

By this stage, the Confederate situation was increasingly hopeless: in August, the settlement of Mobile Bay, Alabama, was taken by a seaborne Union invasion by the end of that month, mounting pressure on the siege of Atlanta in Georgia.

Fall of Atlanta

By this time, vast stretches of Atlanta had virtually been leveled to the ground in the heavy fighting for the city. Finally the Confederates retreated and the Unionists entered the city on 1 September 1864, flags flying and bands playing. The impact on Southern morale was shattering, quite apart from the strategic loss of what was then the biggest city still in Confederate hands.

Shenandoah Valley

Sensing victory, the North pressed home its military victories: a considerable army pursued the daring Confederate general Early into the Shenandoah Valley, defeating the Southerners in three important battles, at Winchester and Fishers Hill in September, and at Cedar Creek in October. The last Confederate troops were driven from Union territory the next month. The string of military victories ensured that Lincoln was, despite earlier dissension, able to win the presidential election of that year, held only in the Northern states.

The March to the Sea

In the closing months of 1864, the Union force under the command of general Sherman, marched east out of Atlanta, striking out along a 97 kilometer (60 mile) front. Chaos and destruction followed in the wake of this march: even though the Union forces were under orders not to destroy private property, massive destruction was caused to plantations across Georgia.

Worse was yet to come: in the wake of the Union advance, freed Black slaves seized the opportunity for revenge upon the White Southerners: rape, pillage and looting became the order of the day, with thousands of such incidents being recorded, and possibly many more going unrecorded in the resultant chaos.

Sherman's forces applied a deliberate scorched earth policy where they went: hoping that the trail of destruction would serve to demoralize the Southerners, as well as cutting off their supplies from the previously wealthy farms.

By 10 December, Sherman had reached Savannah in Georgia: three days later the principle Confederate position around the city, Fort McAllister, fell, and within a week Savannah was in Union hands.

Nashville

From the north, Confederate forces came under attack by the union army advancing south through Tennessee. The Battle of Franklin took place at the end of November 1864, which resulted in yet another Union victory. In mid-December, the Unionists launched a final assault on the last Confederate forces in Tennessee, soundly defeating the Southerners to the point where large numbers deserted and drifted back to their devastated farms in Georgia and elsewhere, the war over as far as they were concerned.

In many Confederate areas, food shortages then began to take on serious proportions, and enthusiasm for the pursuit of the war waned. Large scale desertions became increasingly common and the Confederacy government became more and more an authority in name only.

Fort Fisher

The situation for the Confederates was worsened by the mid January 1865 loss of Fort Fisher on the North Carolina coast, which deprived the South of its last Atlantic port and tightened the Union blockade of the South.

Bentonville

Having effectively routed the Confederate armies in the south, the Unionists then marched north to try and defeat the last major confederate army, still clinging to Virginia and the capital, Richmond. In January, the Unionists marched north with 60,000 men, seizing supplies from the unfortunate Southerners in their path along the way once again.

Reaching the states of South and North Carolina, the Unionists were challenged by a minuscule Confederate force at the Battle of Bentonville in March 1865. The Confederates were easily defeated and the Unionists marched on to Goldsboro, North Carolina.

Burning of Columbia

The march north - led again by general Sherman - again left a deliberate wake of destruction in its path. Once supplies had been seized, it was the norm for houses and farms to be destroyed, and then the White population to be left to the mercies of the freed Black slaves.

As a result of this scorched earth policy, Sherman's name came to be hated in the South, and with good reason. Fifteen towns were burned in whole or in part, but no act of destruction compared with or caused more controversy than the burning of Columbia, the state capital of South Carolina, which saw the city utterly destroyed for no military purpose at all.

Fall of Richmond

Around the Confederate capital, Richmond, Robert E. Lee had been bravely holding out against ever increasing numbers of Unionist troops and equipment. Cut off from new supplies, the situation became increasingly hopeless for Lee. The defeat of a Confederate army at the Battle of Five Forks early in April, signaled the beginning of the end in Virginia and for the Confederation. Fearing encirclement, Lee evacuated Richmond and the city was finally occupied by Unionist forces on 3 April 1865.

The withdrawing Confederate forces engaged the triumphant Unionist forces in a series of battles in the week following the fall of Richmond, but by the end of the first week in April, Lee had been boxed in. With no hope of escape or victory, Lee surrendered to the Union forces under Ulysses Grant on 9 April 1865: the war in the north was over.

The War Ends

Lincoln had ordered Grant to be generous with the Confederates, intending to follow a policy of reconciliation in order to restore the union. However, on 14 April 1865, the president was assassinated by what was assumed to be a Confederate supporter, the actor John Wilkes Booth, in a theater in Washington D.C., and his wishes for reconciliation were never taken up.

On 17 April, the last Confederate forces surrendered in Durham Station, North Carolina, with the last two sizable Confederate armies, one in Louisiana and the other in Texas, both surrendering in May 1865, Realizing that the war was lost and that it was pointless to fight on. Finally the president of the Confederation, Jefferson Davis, was taken prisoner in Georgia on 10 May. The war was over.

Reconstruction

The Civil War settled the two great issues which had plagued the union since its establishment : the power of the federal government and the issue of slavery. Acts passed by the US Congress in 1862, formally abolished slavery in the territories and, arguing that it was a military necessity, Lincoln issued an Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January, 1863, declaring free all the slaves in the rebel states. On 6 December 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in all the states and territories of the United States, was ratified.

Islands Set Aside for Blacks

One of the ways in which Lincoln's avowed policy of not only emancipating the Blacks but of resettling them in geographical isolation from the Whites, came with a Special Field Order, number 15, issued by Union General William T. Sherman in January 1865. In terms of this measure, freed Black slaves were given exclusive rights to and use of a number of islands and parts of the coastal region of South Carolina and Georgia. This effectively created mini Black homelands within the borders of the United States.

The Freedmen's Bureau

In March 1865, the union government then created what became known as the Freedmen's Bureau, a federal agency designed to subsidize and aid former slaves to establish themselves in society after emancipation. This bureau lasted until 1867, when it collapsed in pile of intrigue and corruption.

The Reconstruction Acts

The US congress, now totally dominated by anti-slavery activists who wanted revenge on the South for not only the practice of slavery but also for seceding from the union, passed a series of laws designed to bring the South firmly under control.

In March 1867, the US Congress passed the Reconstruction Act - over the veto of the president who had replaced Lincoln, Andrew Johnson. In terms of this act military governments were set up in ten of the eleven rebel states, the only exception being Tennessee, which had already ratified the most important reform, that of the 14th amendment to the constitution which in essence gave voting rights to all, but which allowed for the mass disenfranchisement of all Whites who had supported the rebel cause.

In each of the other ten states, a military commander was responsible for seeing that each state under his command wrote a new constitution that provided for voting rights for all adult males, regardless of race. Only when the state had ratified its new constitution and the 14th Amendment would the process of political reorganization be complete.

Under these laws, most of the South was divided into five military districts, each supervised by a Union major general in command of a detachment of troops - mainly compromised of freed Black slaves, many of whom were hungry for revenge.

Southern Whites Disenfranchised

Then the constitution of the union was amended (the third section of the 14th Amendment, ratified on 9 July 1868) through which massive numbers of Southern Whites were disenfranchised because they had rebelled against the union. At the same time full voting rights were extended to all the now emancipated slaves; the classification of Blacks as "three fifths of a person" clause in the constitution was revoked by this amendment (although the Amerinds were still specifically excluded from the franchise).

Collapse of Orderly Government

The resulting administrations in the south provoked great resentment, and stoked the fires of racial conflict. Large numbers of Whites were barred from voting, and the legislatures of the southern states were in many cases dominated by illiterate Black former slaves who suddenly found themselves propelled from picking cotton into running the affairs of state. They were of course incapable of running the government efficiently, and the organs of government began to deteriorate almost immediately, with orderly government breaking down in many areas.

Former Black slaves were also placed in many areas as soldiers and officers enforcing law and order over the defeated southern Whites. This provided plenty of opportunities for revenge and abuse. In addition to the appointment of hopelessly incompetent Blacks to fill the positions of government, unscrupulous northerners also took up positions in the southern government, often merely to embezzle funds and enrich themselves: they became known as carpetbaggers.

Northern civil war veterans were put on the official state payroll: southern veterans were consistently denied any form of pension.

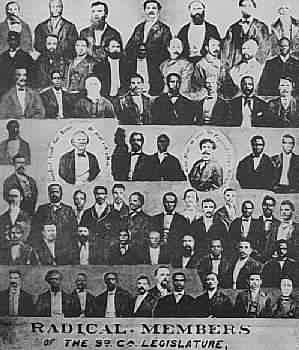

An 1868 photograph of the South Carolina Reconstruction legislature: only 22 of the 94 Black members of the legislature could read or write. The Whites in the legislature were mostly Northerners, as Southern Whites had been disenfranchised and were unable to run for office.

Ku Klux Klan and White Resistance

The racial abuse and incompetence led to the creation of the Ku Klux Klan: an organization founded by a (disenfranchised) former Confederate general, Nathan Bedford Forrest. Although today a small, splintered movement, the original Ku Klux Klan played a hugely important role in overturning the Reconstruction era governments of former Black slaves in many Southern states after the Civil War.

The original Klan, which is not to be confused with the groups calling themselves by that name today, was organized in Pulaski, Tennessee, during the winter of 1865 to 1866, by six former Confederate army officers who gave their society a name adapted from the Greek word kuklos ("circle"). Its activities were directed against the Reconstruction governments and their leaders, both black and white, which came into power in the southern states in 1867.

Dressed in robes with pointed hoods, for disguise and in an early attempt to frighten superstitious Blacks, the Klan launched a campaign of terrorism and violence against Whites and Blacks whom they considered traitors to their cause.

Battle of Liberty Palace

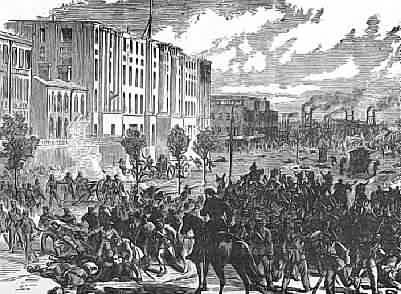

In Louisiana, which saw more than half of the White population disenfranchised, the Ku Klux Klan were particularly active. This White resistance to the overtly racial Black reconstruction government culminated in an open street battle between armed White vigilantes and the predominantly Black federal army of occupation at the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans in 1874, where 3500 league members took over the city hall, statehouse, and arsenal. When the Black federal occupying army arrived, the two sides engaged in a shootout which saw the use of cannon in the city center. Much damage was done and the White vigilantes were forced to retreat.

The uprising was however so serious that a federal army of occupation was to remain in Louisiana for a number of years. Similar clashes took place in the other states: in Tennessee, a race riot erupted in Memphis in May 1866, prompted by a combination of some particularly outrageous reconstruction measures and a wave of Black criminality. Eventually the federal government was forced to impose martial law in the state to restore order.

Resistance to reconstruction turns to insurrection. At the Battle of Liberty Palace in September 1874, several hundred members of the White League did battle with the Black military and police in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana. Both sides used cannon against each other.

Reconstruction Abandoned

This campaign of violence was eventually to be one of the reasons why the Northern States abandoned the Reconstruction campaign, and how formerly disenfranchised Whites were once again granted the vote. Once they had succeeded in taking over the southern legislatures again, the Whites proceeded to dominate through sheer weight of numbers.

The original Klan was officially dissolved by its leader, Nathan B. Forrest, in 1869, but individual groups continued with their campaign of violence.

Finally in 1871, the American president of the time, Ulysses S. Grant, largely in reaction to Southern White complaints that they were disenfranchised while illiterate Blacks were granted the vote, assented to a further change to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing the rights of all citizens.

This effectively abolished the White disenfranchisement laws, and the Klan, its primary task (that of restoring White voting rights) accomplished, then faded into insignificance. A refounded Klan was started in 1915, and although reaching a membership of 3 million after World War 1(its members allegedly including at least one who was later to be elected president of the United States, Warren G. Harding) the Klan was never again to exert the influence that it did in the period leading up to 1871.

Although the image of the Klan suffered because of the numerous incidents of brutal violence in which individual members were involved, there can be no doubt that the southern states were delivered of brutal and incompetent Black overlords by the campaign of resistance organized primarily by the Klan. This fact was publicly acknowledged by the later American president Woodrow Wilson, who, after attending a film showing of David Griffiths epic film Birth of a Nation, remarked that the original Klan had "saved civilization in the South."

Federal Army Withdrawn

There was however another important reason for the fall of the Black governments in the south: the presidential election of 1876 was won by the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, who immediately withdrew the federal troops still supporting the Black and carpetbag governments in the South (particularly in Louisiana and South Carolina). As a result these administrations collapsed, to be replaced by White governments.

White Democrats Win the South

Through the disenfranchisement of huge numbers of Whites, Black voters soon came to dominate the legislatures of the south. Firmly committed to the party of Abraham Lincoln, the Republicans, Blacks provided the vast majority of votes for that party, and without exception every state in the south had a Republican government backed up by a federal army of occupation, many of which were drawn from recently freed Black slave populations.

Blacks also formed a large number of the Republican government's public representatives: in the US Congress there were two Black senators and 14 representatives, whilst dominating the state legislatures and state governments in the south itself.

Virtually all the Whites who were allowed to vote in the South were deeply hostile to this blatantly racial government: particularly when the state legislatures started issuing gratuitous payments to themselves and freed Black slaves under the guise of reconstruction. Taxes virtually tripled in the south as a result of reckless expenditure and pay outs to Black former slaves: this further impoverished the South, which was already struggling with the economic consequences of the war.

Whites Re-Enfranchised

As a result the Whites in the South started voting for the largest opposing party, the Democrats. By 1871, with Whites having been given back the vote, they once again formed the majority of voters in the South. The combination of White re-enfranchisement, violence against reconstruction activists and the withdrawal of the federal army of occupation saw White Democratic governments take over the state legislatures.

The victory of the Southern Democrats in taking power in the south saw the reconstruction policy rejected: taxes were slashed and state expenditure cut, leading to an immediate closing down of the institutions which had allowed the massive corruption by the incompetent Black legislators.

The Democrats also managed to engineer the workings of their own party so that only Whites could attend the primaries, or internal candidate selection procedures. In this way the party remained not only solidly White in terms of support, but also in its public representatives.

Literacy Tests

The White legislatures then sought ways to reduce the number of Black voters, already in a reality a minority. The idea was then hit upon to use literacy as a test: only those persons who could prove a sufficient level of reading and writing ability would be allowed to vote. While this ruling affected a number of Whites, the biggest impact it had was on the Black population, the majority of whom were still illiterate.

Segregation

The Southern Democratic legislatures then enacted a series of segregation laws designed to separate the races in all aspects, from schools through to public places. Many of these measures were in due course to spread to the north of the country a well. In 1875, the US Congress passed a Civil Rights Act of 1875, which barred discrimination by hotels, theaters, and railways. In 1883, this act was declared unconstitutional on the grounds that it interfered with the right of control of access to private property.

Racial Consequences of the War

The after effects of the war on America's White population was vast. At least 250,000 Confederate White soldiers were killed - five per cent of the South's White population. Vast areas of farmland were devastated, and many great cities, like Atlanta, were virtually leveled to the ground.

The South's four million Blacks took advantage of the chaos to seize as much property as was remaining, with their claims often being legitimized by the Black dominated reconstruction governments.

The Civil War severely dented the White population in America: a total of 610,000 Whites were killed - compared to the 4,435 who died during the War of Independence. These figures included 360,000 on the Northern side and 250,000 on the Southern side. Although the North lost more men, that region had a greater White population of some 22 million.

The South however had a population of only some 8 million whites. In percentage terms then, the war was far more devastating to the South than to the North.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.