MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

Chapter Sixty Two

The Second World War

As staggering as had the cost been of the First World War, even that disaster paled into insignificance with the war which became the single greatest conflict of all time: the Second World War. This war saw all of Europe consumed into a conflict in which the total dead of the First World War would be surpassed by the dead of one country alone: it marked the first total and ideological war which Europe had ever seen.

The Treaty of Versailles

It is no exaggeration to say that the Second World War started with the treaty that ended the first one: the Treaty of Versailles, drawn up by the victors of the First World War treated Germany and her allies very badly, blaming them for a war which had been as much the Allies fault as anybody else.

Germany was stripped of huge pieces of territory in all directions.

All told, Germany lost some 25,000 square miles of territory inhabited by nearly seven million Germans: it was a recipe for a nationalist revival.

The union of Germany and Austria - the logical consequence of the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was also strictly forbidden, crippling Austria economically.

Military Restrictions

The German army was placed under great restrictions: limited to 100,000 men, no important naval units; and no airforce at all. These measures were taken as personal insults by the Prussian militarists. Finally, foreign observers were stationed in Germany to keep an eye on factories which might be used to make munitions.

Reparations

Germany was then presented with a bill for the war, again based on the totally false grounds that Germany had alone been responsible for the conflict. An immediate payment of the then amount of $5,000,000,000 was demanded and paid - by the exchange rate of the end of the 20th century, this would probably amount to several hundred times that figure.

This was however was not all: when the Allies finally fixed the full amount of the reparations bill in 1921, it was put at a further $32,000,000,000 - in value at the time. It was not physically possible for Germany to meet this demand, but nonetheless the Weimar government, established by the Social Democratic Party government in Germany, was forced to sign the treaties: thereby earning the enduring hatred of a large number of Germans.

German Economic Collapse

In August 1921, Germany made a payment of $250,000,000 - only a fraction of the amount demanded, but in real terms a staggering amount. Immediately the German economy crashed with this massive pay-out impacting on its foreign reserves.

The German currency failed completely: in January 1923, one US dollar was worth 896 Marks: by November 1923, one dollar was worth 6,666,666,666,667 Marks.

Unable to make any more payments, Germany threatened defaulting on the next reparations bill. In retaliation, the French army then invaded the Saar demilitarized area, establishing martial law in the region. The French used Black African occupation troops in this move: something which caused great resentment in Germany.

Only in 1924, did the American government intervene with a massive loan in terms of a plan drawn up by the banker Charles Dawes: the bail out became known as part of the Dawes plan, which helped to stabilize the German economy, although it was never to recover fully until after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933.

The League of Nations

In 1920, the international community created the League of Nations in an attempt to establish a lasting peace. Despite some small successes, the League never addressed itself to the real cause of conflict: the provisions of the treaty of Versailles. Although the European states tried to address some issues of potential conflict with treaties in the 1920s - most notably the Pact of Locarno and the Kellogg-Briand treaty, nothing was done to lift Germany out of the state in which it had been placed.

The advent of the Great Depression in 1929 made the economy even worse and paved the way for the coming to power of the German nationalist Adolf Hitler.

The state that Hitler created is the subject of another chapter: suffice to say here that it was by exploiting German grievances with the Treaty of Versailles, both in terms of national pride and territorial losses; and by pulling the German economy back on track, that Hitler was able to come to power with the support of the majority of Germans.

Hitler Overthrows the Treaty of Versailles

An important part of Hitler's political program was the overthrow of the Treaty of Versailles: as a first stage he unilaterally re-armed Germany and refused to pay any more reparations.

Then Hitler started retaking the areas lost by Germany in which Germans still lived: the Saar was occupied in 1936 (the French had left a while earlier, but the region still was officially a demilitarized zone); in 1938, Austria was annexed to Germany and in that same year Czechoslovakia was broken up, with the region in which a majority of Germans (3.5 million of them) lived, the Sudetenland, being formally annexed to Germany.

Further parts of Czechoslovakia that were ethnically Polish and Hungarian were given to those two countries; the eastern section of the country was made independent as the Slovak Republic. The remainder of Czechoslovakia was then made into a German protectorate.

The Polish Question and the Outbreak of Hostilities

Then Hitler turned his attention to the Polish corridor made up of former German territory and the city of Danzig. At first restricting himself to requesting road and rail links between Germany and East Prussia, Hitler decided on a military option after these overtures were rejected by the Poles. Alleging that Germans were being maltreated by the Poles - and in certain areas they were - Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939.

The Germans hoped that France and Britain would not go to war over the issue - Hitler drew the analogy that Germany would not go to war with France if that country claimed one of its cities back from foreign rule. This hope was misplaced: on 3 September, France and Britain both declared war on Germany for the act of invading Poland.

The Second World War had started, on the surface caused by Germany reclaiming territory inhabited by Germans which had been torn off that country by the Treaty of Versailles.

The Polish Campaign

Germany put 1.5 million men into battle: the Poles met them with a numerically superior force of 1.8 million. The Germans had however learned the lessons of the First World War well: they had invested heavily in the building of tanks and had developed the concept of mobile war in these armored vehicles: the "blitzkrieg" or lightning war, was unleashed on Poland.

The Polish army, expecting head on static conflicts as had happened in the First World War, were no match for the mobile Germans. By 17 September, the Germans had overrun huge areas of the country and had encircled Warsaw, routing the Poles in every major engagement of the campaign.

Soviet Union Invades

On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the East: an earlier treaty between Germany and the Soviet Union had provided for such an eventuality. The Soviets quickly rolled up the by now panicked Poles, and within three days Poland had been divided between German and Soviet troops. The last pockets of Polish resistance surrendered on 6 October 1939.

The Soviet Union's invasion was a mirror image of the German invasion: yet here came the best indication that there was something more to the war than just Britain and France resisting German aggression, as the conventional historical accounts would have everyone believe.

For if France and Britain had declared war on Germany for the aggressive act of invading Poland, then surely for the sake of consistency they should have declared war on the Soviet Union as well, when it too invaded Poland.

The reason for this clear and obvious double standard was the overtly racial ideological element which Hitlerian politics had introduced into the war: this is discussed in a later chapter.

The Sitzkrieg

Germany only annexed that part of Poland which had been German before the First World War: the rest of the country was made into a protectorate, while the eastern part was annexed by the Soviet Union.

France and Britain were astounded at the speed of the Polish campaign: the French only launched a half hearted attempt to attack from behind their heavily fortified Maginot line of concrete emplacements along the border with Germany. The Germans had built a similar fortified wall: the Siegfried Line, and the French attack petered out before it even reached the German line.

Hitler than made an offer of peace to Britain and France: he had never declared war on them (and never did during the entire course of the war) and did not seek a war with them. Making the offer of peace in a speech in Berlin, Hitler put no pre-conditions other than that the two European nations recognized the right of Germany to re-incorporate the German lands in Poland. The offer was rejected out of hand by both the British and French governments.

Still no military action took place: caught in between building up military reserves and trying to end the war by diplomatic means, Germany kept behind its Siegfried Wall. France, waiting for the British to arrive in significant numbers, kept behind their wall: both sides feared above all else a repeat of the static trench war of 1914-1918. The Sitting War, or Sitzkrieg, continued from September 1939 until May 1940.

The Soviet-Finnish War

At the end of November 1939, the Soviet Union then invaded Finland. Despite being outnumbered five to one, the Finns fought bravely and inflicted massive losses on the Red Army. Fighting on into the new year, without aid or support from Britain or France, Finland only lost small pieces of land before fighting the invaders to a standstill. On 8 March 1940, the war came to an end, with Finland only ceding the small slice of territory which the Soviets had managed to grab.

Once again Britain and France refused to declare war on the Soviet Union for doing exactly what Germany had done to Poland: this blatant double standard once again proving that the declaration of war against Germany was motivated by an underlying ideological reason, rather than just a desire to protect small nations against aggression.

Denmark and Norway

Britain in the meanwhile decided to land troops in Norway to seize the Swedish iron ore mines which were continuing to supply Germany with raw iron. On 6 April, a large British and French expeditionary force sailed for Norway; then the British navy proceeded to lay mines outside the Norwegian harbor of Narvik, hoping to sink some German ships carrying ore back to Germany.

The mines were laid on 7 April: Hitler, sensing that something was afoot, hastily pulled together an invasion force which sailed the same day, landing in Norway on 9 April.

On the way, Germany occupied Denmark to use that country's ports and airfield. The small nation surrendered immediately and was relatively well treated by Germany for the rest of the war.

The German landings in Norway succeeded everywhere except in Narvik, where a small German force of 4600 men were faced by 24,600 British, French, and Norwegian troops. The minute German force held out, but by the first week of June had been pushed back against the Swedish border. They were on the point of surrendering when the French and British withdrew to go the aid of the then rapidly deteriorating military situation in France.

Norway then fell completely under German occupation, never to be disturbed again for the entire duration of the war, with the occupation army only withdrawing after the German surrender in 1945.

Case Yellow: The Invasion of France

On 10 May 1940, Germany broke the Sitzkrieg and attacked in the west, following a plan worked out by Hitler personally which he called Case Yellow: created over the objections of his generals. Employing the same tactics they had used in Poland, the tight German armored divisions raced past British and French troop concentrations, surrounding them into isolated pockets where their dispersed tanks and armor was of little use.

This tactic was especially advantageous in the light of the fact that the opposing armies were, in terms of numbers, evenly matched.

On the first day of the invasion, German airborne troops landed in Belgium and the Netherlands. In Belgium. German paratroopers succeeded in knocking out the Belgian concrete forts of Eben-Emael, swiftly defeating that small nation's only major line of defense. In the Netherlands, Dutch resistance crumbled after a small German bomber force attacked the inner city of Rotterdam, killing several hundred civilians.

The British and French forces in northern France then moved into Belgium to meet the oncoming Germans. Then Hitler launched what would be his master stroke in the West: the main German force attacked in the center of the border between France and Germany, the Ardennes forest.

With the tank, or panzer, army in the lead, the Germans raced past the Maginot line and then swung northward, covering 400 kilometers (250 miles ) in 11 days: mobility unheard of in any war till that time. Racing for the coast, the panzers encircled the British and French forces busy moving into Belgium. The Allied army was cut into two by this move.

Dunkirk

By 26 May - 16 days into the campaign - the Allied army in the north was trapped along a coastal enclave next to the town of Dunkirk. For reasons which have never been explained (the most common belief is that Hitler wanted to let the British escape so as to facilitate a peace with them at a later stage) the German panzers were deliberately stopped outside the town.

The pause in the German attack allowed the entire British Expeditionary Force - some 330,000 men - be evacuated by an astonishing flotilla of British naval and civilian ships, back to England across the channel. Although all the men were evacuated, they left behind tons of sorely needed equipment on the beach.

The Defeat of France

With the main body of the British force gone, the Germans turned south and west once again: ignoring the French troops still sitting in their virtually impregnable Maginot Line, the German tanks drove deep into the French countryside. They met only scattered resistance: more often than not, when French soldiers surrendered, their weapons were taken from them and they were sent home by the Germans who did not want to burden themselves with prisoners.

Finally on 17 June, the French premier, Marshal Henri Petain, the First World War hero who had held the French together in their darkest hour of that war, realized that the situation was militarily hopeless. He asked for an armistice which was signed on 25 June. France had been beaten by Hitler's plan in 46 days.

The armistice gave Germany control over northern France extending into a strip down the Atlantic coast: the rest of France was left independent under Petain, with its capital at the city of Vichy, causing this territory to become known as the Vichy republic.

Operation Sea Lion

The invasion of France had been followed in Britain by the appointment of Winston Churchill as prime minister, who proved to be an able war leader whose carefully media cultivated image in many ways captured the dogged resistance put up by the British when that nation was the only major power on the European continent which had not been overrun by Germany.

The English channel had been the only physical reason why the German tanks had not rolled on to occupy Britain at the same time that France was overrun: certainly after the defeat at Dunkirk the British army barely had enough armor or heavy weapons left to ward off any significant German attack.

The Germans then drew up a plan to invade Britain: called Operation Sea Lion, it consisted of crossing the channel in invasion barges and landing on the southern coast of England. Before this could be achieved, Germany had to achieve air superiority to make up for their overwhelming inferiority at sea. The mighty British navy could knock out almost anything put to sea and could only be warded off by superior air power. The war for Britain then switched a battle in the air.

The Battle of Britain

When Germany had invaded Poland in September 1939 and the Netherlands in May 1940, pinpoint air strikes against civilian towns had been carried out in Warsaw and Rotterdam: both had served effectively to wear down the resistance of the invaded countries.

So it was that when Winston Churchill became prime minister of Britain on 10 May 1940, his first act the next day was to announce that German cities would be targeted for bombing attacks. The same month the first German cities were bombed by British aircraft.

The German airforce however avoided bombing British cities, concentrating on the strategically more important airfields and ports, launching the first of these major raids during August 1940.

The British came up with a surprise weapon: the Spitfire fighter, which at first outclassed almost all the fighters the Germans put into the battle, apart from the Messerschmidt Bf109, with which it was on virtually equal terms. However, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) took a heavy toll on the other German aircraft. The famous Stuka dive bomber, for example, was shot out of British skies in such numbers that after a few weeks they had been withdrawn from the battle.

German air losses mounted: the bravery of the British aircraft teams in defending their homeland has become legendary: certainly it was their efforts which caused the Germans to shelve Operation Sea Lion indefinitely by the end of 1940.

The Blitz

In the interim, British bombers had been raiding German cities for almost four months: finally, after a bombing raid on Berlin itself, Hitler authorized the Luftwaffe to start bombing British cities in return. Selected British cities were then targeted: London, Coventry, Birmingham and Sheffield came in for particularly heavy bombing, and the raids became known as the Blitz.

Despite large scale destruction, the death toll was surprisingly low: in Coventry, only 380 civilians died as a result of the bombing raids throughout the course of the entire war: and total British civilian losses during the war due to German bombing was around 60,000.

To put this into perspective, more than 500,000 German civilians died in the Allied bombing of German cities during the war: in one raid, on Dresden in 1945, 135,000 German civilians were killed in a single raid.

Nonetheless, the Blitz caused great hardship and forced the British to evacuate virtually all children out of the major cities to rural destinations, splitting families and greatly adding to the misery of wartime Britain. However, most importantly, the Blitz did not break the spirit of the British people or their preparedness to pursue the war.

Left: The ruins of the German city of Dresden, where 135,000 German civilians died in one bombing raid a few days before the war ended: more than all the Japanese who died in both the atom bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki put together. Right: St. Paul's cathedral in London during the Blitz. 60,000 Britons were to die in all the German bombing raids on that country during the entire war.

Italian Misadventures

The Italian leader, Benito Mussolini, had allied himself to Germany before the war in a 1938 alliance known as the Pact of Steel or the Berlin - Rome Axis: as a result this alliance was known as the Axis. In the closing week of the German campaign against France, Mussolini entered the war on Germany's side.

The Italian declaration of war against Britain caught a large number of Italian ex-patriats in Britain by surprise: the British government detained thousands of Italians and kept them without trial for the duration of the war in prisoner camps.

Mussolini launched an attack on France from the Italian side of the French-Italian border immediately after declaring war on that country. The attack was a total failure and French troops even crossed the border into Italy after driving off the initial Italian assault. Only the collapse of the French armies in central France saved Mussolini from an embarrassing defeat.

Eclipsed by Hitler in Western Europe, Mussolini then turned his attention south: in September 1940, he launched an attack on British held Egypt from the Italian colony of Libya, which was easily driven off.

The British then in turn invaded Libya, and started to push the Italians back into that territory. Undaunted, Mussolini then launched an invasion of Greece from the Italian held territory of Albania, in October 1940. Soon the Greeks had defeated the Italian forces as well, and pushed deep into Albania in retaliation. British forces then landed in Crete and Greece to aid the Greeks.

On all fronts then, Mussolini's endeavors faced catastrophe: his inept invasion of Greece had even allowed the British back onto mainland Europe: Hitler was forced to act to bring the situation under control.

The Balkan Campaign

Germany quickly prepared an invasion force to drive the British out of Greece. To reach Greece, German forces had to cross a number of other Eastern European countries: Rumania, Bulgaria and Hungary had formally allied themselves to Germany and gave permission for German troops to move through their countries: only Yugoslavia refused and had to be subdued by force.

The German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece began in early April 1941: by 13 April, Belgrade had fallen and the Yugoslav army surrendered the next day. The Germans split Yugoslavia up, giving the Albanian dominated region of Kosovo to Albania and letting Croatia become independent: however for the rest of the war, Yugoslav guerrillas fought a merciless war against German troops in the region, and were never completely subdued.

By 9 April, the Germans had smashed the relatively strong Greek army of some 430,000 men: the British expeditionary force in that country was forced to retreat south with its entire force of some 62,000 men. By the end of April, all of Greece had been overrun: the British had withdrawn to Crete, an operation which cost them 12,000 men.

Even there they were not safe: a German airborne invasion in May 1941, (the first in history, discounting the comparatively small landings in the Netherlands in May 1940) drove them off that island, although the German losses were so high that they were never to try an airborne assault on this scale again.

North Africa

Hitler also sent a small German panzer division to Libya to aid the Italians there: under the able leadership of General Erwin Rommel, this German unit, to be known as the Afrika Korps, soon won renown as daring and tactical fighters, quickly stabilizing the military situation and even pushing the British back into Egypt.

The De Facto War

Although officially neutral, the United States made its partiality for Britain known from the beginning, even duplicating the British overlooking of the Soviet Union's invasion of Poland and Finland as a reason to censure that country. In March 1941, the US Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act and appropriated an initial $7 billion to lend or lease weapons and other aid to any countries the president might designate as in America's interests: this of course meant Britain and immediately a flow of material and other supplies started to the beleaguered island.

In July 1941, the US stationed troops in Iceland and the American navy was escorting convoys supplying Britain in waters west of Iceland. In September 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized American ships doing convoy duty to attack German warships or submarines. America was as good as at war with Germany already.

Barbarossa

Hitler had decided as early as December 1940 that an invasion of the Soviet Union would have to be made: apart from the fact that the Communists were his traditional political foe, all evidence showed that the Soviets were planning to attack Germany at some time during the course of 1941 or 1942. Given all the factors, Hitler decided to strike first.

An invasion plan was drawn up under the code name Barbarossa: after the ancient German king of the same name. This plan entailed a series of quick thrusts through western Russia, halting at the Ural mountains.

Hitler never foresaw going further than this, nor of concluding a treaty with the defeated Russians: rather he saw the territory east of the Urals as alien land which he neither wanted nor wished to subdue.

Originally, Hitler planned Barbarossa for early 1941 so that the campaign could be completed before the advent of the notorious Russian winter. This early invasion had to be postponed due to the disastrous invasion of Greece by Mussolini.

Forced to intervene in Greece and Yugoslavia, the Germans lost a critical month in organizing the invasion of the Soviet Union: the result was that the Russian winter did indeed set in before their primary objectives were reached, forcing them onto the defensive for the first time in the war.

This loss of initiative was the first important German reverse of the war: if ever there was a turning point in the war, it was the delay caused by Mussolini's clownish invasion of Greece. Ultimately Hitler was undone by his choice of allies, rather than by his choice of foes.

The Greatest Land War of All Time

Finally, Barbarossa was executed on 22 June 1941. More than 3 million German troops took part in the assault, which was spread from the Baltic Sea in the north right through to the Black Sea in the south. It was the beginning of the greatest land war of all time, never equaled since.

The Soviet Army also had just over 3 million men in its western army (it had more reserves in the far east) and outnumbered the Germans by two to one in tanks and by two or three to one in aircraft. The Soviet tanks, in particular the T-34s, were far superior to anything the Germans had at the time: the first T-34s captured intact were dragged away by German engineers for inspection, and it was only much later in the war that the Germans were able to put anything as effective into the field.

Despite the odds, the three German army groups: North, Center, and South, made tremendous speed in rushing towards their three objectives: Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev respectively.

The speed of the initial advances served to give credence to the German hope that the campaign could be finished before the end of the year: however the delay caused by the Italian debacle would yet catch up with the Germans.

The British offered the Soviet Union an immediate alliance, with Churchill personally issuing the offer: Roosevelt also offered lend-lease aid, which soon came flooding into the Soviet Union in such quantities as to significantly affect the course of the war.

Massive Soviet Losses

By the end of the first week in July, the German Army Group Center had taken 290,000 prisoners and had passed Minsk: in early August, the Germans crossed the Dnieper River, the last natural barrier west of Moscow, and destroyed a Soviet army at Smolensk, taking another 300,000 prisoners.

By early September, Leningrad, the former city of Petrograd (now known as Saint Petersburg) had been encircled by Army Group North. The Finns, who had participated in the invasion in the far north, also lay siege to Leningrad. Soon a great famine spread through the city, with its only supply route being across the frozen lakes, an extremely hazardous route.

In mid-September, Army Group South captured an incredible 650,000 prisoners in an encirclement to the East of Kiev. By late October, Army Group Center was once again pushing east towards Moscow. On the way, it captured yet more prisoners: this time some 663,000 Red Army soldiers fell into their hands.

In less than four months, the Soviets had lost more than 1.8 million men in prisoners alone: it became a serious logistical problem for the Germans in handling the prisoners: in effect they all of a sudden had to feed and provide shelter for a mass of men two thirds the size of the German army itself.

Such losses had not been sustained by an army before in history, yet the Soviet ability to fight on serves as a striking example of how vast this particular campaign was; and also of the massive reserves the Soviets could call upon.

The Winter Sets In

By late November, two German advance units penetrated right into the suburbs of Moscow: one advance unit came to within eyesight of the onion domes of the Kremlin itself. Then the Russian winter set in with a viciousness which the Germans were not expecting: many were also not equipped for the winter, and the month delay in launching the campaign finally tripped up the Blitzkrieg war.

With victory in Moscow in sight, the German tanks, vehicles and even guns froze: hundreds of soldiers froze to death in the cold snap which halted the advance in its tracks. On 5 December the advance unit commanders reported that they could go no further: they were not equipped to fight under the freezing conditions and they were unable to dig in because the ground itself was frozen.

It was impossible even to bury the dead: not that they needed burying, as they did not decay in the frozen ice. The German commanders reported finally that the conditions and lack of winter equipment for the German troops had caused morale to sink to a low as then unseen amongst the soldiers.

Soviet Counter Attack Succeeds

The Soviets, all well equipped for the harshness of the winter, had brought up reserves from the Far East and exploited the halt in the German advance to press home a counter attack. With their vehicles, equipment and weapons specifically designed to fight in sub-zero temperatures, the fresh Soviet troops devastated the advance German units and the invaders were driven out with great ease.

The retreating Germans left behind their frozen tanks, trucks and weapons, being forced to flee on foot. It was the first major defeat for the Germans of the war. Fighting a desperate rear guard action, the Germans managed to plug the holes in their front line by the end of December: but the immediate threat to Moscow was lifted and the plan to destroy the Soviet Union by the end of 1941 had been wrecked.

Japanese Power

In the Far East, the recently industrialized Japan had gained in confidence since its defeat of the Russians in the 1905 war at Port Arthur on the Chinese coast. Increasingly, Japan saw itself as the regional power - which it was - and in 1936, became embroiled in a war with China over land which saw the Japanese army invade Chinese territorial space. In retaliation, the United States and Britain imposed an oil embargo on Japan in 1936, hoping to starve the mineral poor island nation out of further expansionist moves.

Japan then signed the anti-Communist anti-Comintern pact, indirectly allying itself with Germany and Italy. Despite this, the Japanese remained neutral in the opening phases of the war; even signing a treaty with the Soviet Union guaranteeing that the latter country would never be subject to attack by Japan. This treaty enabled the Soviets to withdraw a large part of their eastern army to the west where they were instrumental in the Soviet victory at Moscow in December 1941.

By 1941, the oil embargo was starting to seriously hurt Japan: as Germany's victory appeared to loom large that year, the Japanese decided that to survive they would need to capture the oil and mineral reserves of South East Asia.

The Japanese realized however that the Americans, who had objected to the Japanese-Chinese War, would never peacefully let Japan seize even more territory. However the Japanese also believed that the Americans would not fight for long and soon leave Asia to itself: in this they made a major miscalculation.

Pearl Harbor

In terms of the Japanese plan, a swift campaign would see their troops take Burma, Malaya, the East Indies, and the Philippines in quick succession: the only thing that stood between them and these possessions was the presence of the US Pacific fleet based at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

It was decided to try and cripple the American fleet with a surprise air attack on the morning of 7 December 1941, in order to prevent the Americans from interfering with the Japanese invasions. The American military intelligence records reveal that the US Army intelligence was aware of the Japanese plans, including the attack on Pearl Harbor itself. A warning was in fact sent to the military base, but mysteriously delayed, only arriving after the attack had started.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor sank 21 ships, including eight battleships; 188 American aircraft were destroyed on the ground and 2,200 American soldiers and sailors were killed. The attack changed public opinion in America overnight: from a strongly anti-participation in the war sentiment, the American public swung solidly behind Roosevelt who led the US Congress into declaring war on Japan.

The results of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 1941: American ships on fire. 2,200 men were killed in the attack.

Germany Declares War on America

America had, as outlined above, been all but committing active troops to the war against Germany before Pearl Harbor: now, partly out of an acceptance of the de facto situation and parity out of what was clearly a misplaced loyalty to Japan, Germany then declared war on America on 11 December, an example followed by Italy on the same day.

This was the second great error on Hitler's part (the first being his alliance with Mussolini). By declaring war on America, he gave Roosevelt the excuse to commit troops and the full force of American industrial power to the war in Europe.

Germany Lost the War in 1941

The events of 1941 were catastrophic for Germany, even though in terms of outright military defeats, the retreat before Moscow had been relatively minor. However, America's entry into the war meant that an overwhelming industrial power, whose production and military hardware output Germany could not hope to match, was now formally ranged against the latter country.

In addition to this, the failure to knock the Soviet Union out in 1941 meant that a long war of attrition in the east would continue for years. The Soviet Union, having the greater population and therefore greater reserves, could not do anything but win a war of attrition.

Also, the German field code, previously thought unbreakable (developed by a German engineer using a device which randomly selected numbers off a spinning wheel - dubbed the enigma machine) was cracked by a superb British intelligence unit at Bletchley Park, England, with the aid of a huge analog computer built specially for the purpose. For the greatest part of the war, all of Hitler's commands were known to the Allied intelligence service, very often even before the German commanders to whom they were sent, had received them.

Germany therefore never stood a realistic chance of winning the war after December 1941, and it was only with a superhuman effort that it continued fighting until 1945.

The War in the Pacific

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese quickly advanced through their target territories: by the end of December 1941, they had occupied British Hong Kong, the Gilbert Islands and the islands of Guam Wake. In addition they had made significant advances into British Burma, Malaya, Borneo, and the Philippines.

By February 1942, British Singapore had fallen to the Japanese army, and the next month they occupied the Netherlands East Indies and landed on New Guinea. The main force of American and Philippine armies on the Philippines surrendered in Bataan in April 1942, and the surrender of Corregidor in early May, sealed the fate of that country.

The Japanese then launched a bid to seize Port Moresby on the south eastern part of New Guinea: the Americans, being able to read the Japanese signals, sent a naval unit to attack the invasion force. The resultant May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea, fought exclusively by aircraft launched from aircraft carriers, saw the first Japanese defeat. The American force overwhelmed their Japanese foes and the invasion of Port Moresby was abandoned.

The Battle of Midway

One month after the Japanese defeat at the Battle of the Coral Sea, an American air and naval attack on a powerful Japanese fleet consisting of nine battleships and four aircraft carriers, saw all four carriers being sunk. Although the Japanese navy had more carriers, this engagement, known as the Battle of Midway, dealt the Japanese a severe blow.

Cut off from the White world's technology, Japan never managed to build a carrier during the war again, placing it at a permanent disadvantage. This isolation of Japan from the White technology centers of Europe and North America would dog Japan in other areas as well: in aircraft design, for example, by 1945, the Japanese airforce was still equipped with virtually the same aircraft with which it had started the war. The main fighter they possessed was the Mitsubishi Zero - while this airplane was approximately the equivalent of the average American fighter in mid 1941, by 1945 it had been hopelessly outclassed by the highly developed American P-51 Mustang fighters, not to mention comparison with the European aircraft: the fabulous Spitfires, Hurricanes and Mosquitoes of the British Royal Air Force, and the Me 262 jet aircraft of the Luftwaffe.

The stagnation of Japanese technology during the war period, when it was cut off from the White technological centers of America and Europe, tells a story all by itself.

Rommel Advances in North Africa

In North Africa, the German expeditionary force had managed to initially drive the British back and had laid siege to the important town of Tobruk. German reinforcements trickled in, and by early December 1941, the British had managed to relieve Tobruk and take the equally important town of Benghazi.

It was only in January 1942, that Rommel managed to draw up enough reserves to counter-attack: a successful drive pushed the British back towards the Egyptian border. In June, Tobruk finally fell to the Germans and Rommel pushed on into Egypt itself, only finally running out of steam before the town of El 'Alamein. Rommel had badly overstretched his supply lines with the extent of the advance: this was to cost him dearly.

New Campaign in the East

As the 1941/1942 Russian winter lifted, the Germans launched a new offensive in the east, hoping once again to knock the Soviets out with a series of dramatic victories. The year started well for the Germans: a battle near Kharkov to the south of Leningrad and an invasion of the Crimea - which saw the city of Sebastopol fall after a tremendous siege - saw another 500,000 Red Army soldiers being taken prisoner.

Then on 28 June - virtually to the day a year after the initial invasion, the second great German offensive in the east was launched. In four weeks, they seized vast areas of land, penetrating hundreds of kilometers past Moscow to the south.

The German force was then split into two: one unit raced south into the Caucasus to take the oil fields at Groznyy and Baku. By August, the invasion of the Caucasus had penetrated 300 kilometers into Soviet territory, and by early September the northernmost unit had reached the outskirts of the city of Stalingrad on the banks of the Volga River.

Once again the Germans seemed poised for total victory: but the sweep south and south east had not seen the massive Soviet surrenders so characteristic of the campaign till then. Soviet losses had been light: all the while German supply lines had been stretched to the point where the sheer distance covered meant that the effective fighting strength of the German Army Groups was nowhere near what they should have been.

By this stage, the Soviet Union had also been receiving vast amounts of American material aid: this, combined with the manpower reserves of the Soviet state - three times that of Germany - meant that the Soviets could launch a devastating counter attack: they chose Stalingrad as the most exposed and easterly part of the German lines to do so.

Guadacanal

In the Pacific, American troops invaded the island of Guadacanal in August 1942, starting a series of "island hops" which would characterize the rest of the American war against Japan. The Japanese fought tenaciously for all the territories they had occupied: it took a series of major naval battles and vicious hand to hand fighting before Guadacanal was cleared of the last Japanese soldiers in February 1943.

El Alamein

In North Africa, the German advance into Egypt was reversed by a brilliantly planned counter attack by the British Eighth Army - which now included South Africans - commanded by general Bernard Montgomery. By 5 November 1942, the Afrika Korps was in retreat out of Egypt.

On 8 November 1942, a combined British and American force then landed in Vichy French held Morocco and Algeria, behind the German supply lines which started in Tunisia. Startled, the Germans rushed reinforcements to Tunisia, simultaneously occupying Vichy France in the process. Fighting desperate rear guard actions on two fronts, Rommel managed to halt both the American and British advances in Algeria, most famously at the February 1943 Battle of Kasserine Pass: but the overwhelming numbers of the Allied forces eventually won the day.

Advancing through Libya from the East and from Algeria in the west, the Afrika Korps was rolled up and surrendered in May 1943: the Germans and Italians lost 275,000 prisoners as a result.

The Soviet Victory of Stalingrad

On the Eastern Front, the German advance to the Volga River and into the Caucasus added a staggering 1100 kilometers to the front line. The sheer length of this advance meant that there were not enough German troops to man the entire front, a serious miscalculation on Hitler's part.

The Germans then put the armies of their poorly trained and equipped allies into the holes in the front line: these included Rumanian, Italian and Hungarian armies: none of whom had the battle experience or equipment of the German forces which were tied down at the very points of the advance.

On 19 November 1942, while the German forces had reached the banks of the Volga River and had occupied most of the city of Stalingrad itself, a huge Soviet attack smashed through the Rumanian forces positioned to the north and south of the main German army: within three days the Soviets had surrounded Stalingrad and the German invaders.

Efforts to relieve the surrounded army failed and Hitler forbade the army to withdraw, as it might have been able to do at the early stages. This order could have only one consequence: on the last day of January 1943, the German forces in Stalingrad were forced to surrender.

Some 200,000 men were lost as a result. The Italian, Hungarian and Rumanian armies collapsed and the Germans were forced to retreat from the Caucasus to patch up the holes in the front: virtually all the land gained during the 1942 offensive was lost.

Air Raids on German Cities

By 1943, the British and Americans had launched a strategy of trying to demoralize the German civilian population by launching 24 hour round the clock incendiary bombing raids: the British by night and the Americans by day. Civilian targets were therefore specially selected, with huge losses for ordinary Germans: in raids on Hamburg in July 1943, 50,000 civilians were killed in four days.

The Luftwaffe concentrated its forces over the skies of Germany: flying missions as strenuous as anything undertaken by the British during the Battle of Britain, they managed to halt the major daylight attacks by October 1943.

Such serious losses were inflicted on the American bombers that they were grounded until modifications were made to the P-51 Mustang fighter to enable it to escort the American bombing missions: when this happened at the end of 1943, the daylight bombing resumed, with the long range American fighters taking the pressure off the bombers by engaging the Luftwaffe in combat. From then on the Allied bombing campaign of civilian targets in Germany would not cease until the very last days of the war.

The Biggest Single Battle of All Time: Kursk

On the Eastern Front, the Germans launched one final attempt to grasp the initiative against the Soviets. This came with the Battle of Kursk, fought from 5 July to 12 July 1943. This was the largest single land battle ever fought in history: more than a million men and over 5000 tanks engaged one another in a seven day encounter.

The German offensive attempted to surround a Soviet force in Kursk: the Red Army prepared its defenses well, and on the seventh day the German advance had been halted. Hitler then called off the operation because the Americans and British had landed in Sicily, and he needed to transfer divisions to Italy to shore up that new front.

If any Germans had begun to doubt that they could not win the war after Stalingrad, the failure to win the Battle of Kursk must have confirmed it.

Mussolini Dismissed from Office

On 10 July 1943, at the height of the Battle of Kursk, Allied armies invaded Sicily from North Africa. In five weeks, they cleared the island of all Italian and German troops - although the former started to surrender in large numbers, many being unwilling to partake in which was increasingly looking like a German defeat.

The Italian king, Emanuel III, then used his constitutional powers and fired Mussolini from office (the fact that Mussolini could be removed from office in this way belies the often made allegation that he was responsible to no-one) and appointed a new government, which then negotiated a surrender to the Allies on 8 September. Mussolini was placed under arrest and held at a mountain top hotel which had hastily been converted into a prison, while the new Italian government waited for the Allies to tell them what to do with him.

The Invasion of Italy

The Allies had invaded the Italian mainland itself before that country's government surrendered, occupying a large slice of the tip of Italy north of Naples across that peninsula to the Adriatic Sea. The German forces rushed to Italy from the Eastern Front were battle hardened veterans; by the end of the year had halted the Allied advance 100 kilometers south of Rome, at the Liri River and Monte Casino. An Allied landing of 50,000 men behind the German line at Anzio failed to dislodge the Germans who had in the interim also freed Mussolini and had installed him as leader of a new Italian government.

Island Hopping in the Pacific

During May 1943, American troops retook the island of Attu in the Aleutians in a hard-fought, three week battle, while a combined American and New Zealand army took the Solomons islands, landing a major beachhead on Bougainville by November.

Australians and Americans then captured the East coast of New Guinea; and then several island groups were captured in succession. The Gilbert islands were captured in November 1943: however the Japanese resistance got all the more fanatical with the passing of time. Some 3,000 Americans were killed seizing the 291 acre island of Beito in the Gilbert islands. Cape Gloucester, New Britain, was taken in December 1943; the Admiralty Islands and the Marshall islands in February 1944; and by March 1944, Emirau Island had been retaken.

German Retreat

The Red Army followed up its successful defense of Kursk with an August 1943 offensive in the region against the weakened German forces: by the middle of the month, the Red Army attack had been expanded south and the Germans were firmly in retreat.

In mid-September, Hitler ordered the major German army in the south to retreat to the Dnieper River: he had learned from his error at Stalingrad and could not afford to lose another entire army. In the Crimea however, another German army group was surrounded by a renewed Red Army assault south: they were eventually to be devastated and their 150,000 exhausted survivors forced to surrender when that peninsula was completely retaken by the Soviets in May 1944.

Advancing steadily westwards, the Red Army then recaptured Kiev, continuously driving the defeated Germans before them. In January 1944, a Soviet offensive raised the siege of Leningrad and drove Army Group North back to the Narva River-Lake Peipus line, where fanatic resistance by a Waffen-SS (fighting SS) army checked the Soviet advance for over six months.

By April 1944, virtually all of Soviet territory except Byelorussia had been cleared of German troops: in June 1944, a massive Soviet assault took Byelorussia. Outnumbering the German defenders by ten to one, the victory was swift.

By the third week, the Soviets had advanced 300 kilometers, capturing over 57,000 German prisoners. The Red Army stood at the German jump off points of June 1941, ready to turn the tables in a final push into Eastern Europe.

Overlord

In the west, the Americans, had been massing a huge army in Britain, ready to launch an invasion of Western Europe and thereby open a third front to engage the already overstretched Germans. The invasion, code named Operation Overlord, took place on 6 June 1944, with dramatic dawn landings on the beaches of Normandy.

Taken by surprise (the German high command had been expecting the invasion to take place further north on the French coast) the Germans were pushed back: by this time the skies belonged to the Allies and their air superiority had already virtually won the land battles, as the Germans could not move any troops or armor around without attracting immediate attention from hostile aircraft.

The German commander in the west, Rommel, was himself severely wounded in an Allied aircraft attack upon his personal car: he never fully recovered from his wounds before he was forced to commit suicide after being implicated in a plot to kill Hitler in July 1944.

By the end of June, the Allies had managed to land over 850,000 men and 150,000 tanks and other vehicles in Normandy: this, combined with the overwhelming air superiority, made the outcome in the west only a matter of time.

The July Plot

A group of German officers and civilians concluded in July, that getting rid of Hitler offered the last remaining chance to end the war before it swept onto German soil from two directions. On July 20, they tried to kill him by placing a bomb in his headquarters in East Prussia. The bomb exploded, killing and wounding a number of his senior officers but inflicting only minor injuries on Hitler.

Afterwards, the German police hunted down everyone suspected of complicity in the plot and those who were not killed during the suppression of the conspiracy (such as Count Claus von Stauffenberg, the man who planted the bomb) were hanged after spectacular show trials. Millions of still faithful Germans were shocked at the attempt to kill Hitler; he emerged from the assassination attempt more secure in his power than ever before.

France Cleared of Germans

By 25 July, the Allied armies proceeded to break out of the Normandy beachheads they had established. Their overwhelming material superiority was only challenged in part by the limited number of new German super tanks, the Tiger and Panther models. These new weapons were too little, too late; by late August, the Germans had been driven across the Seine.

On 25 August, the Americans, in conjunction with General Charles de Gaulle's Free French and Resistance forces, occupied Paris after the retreating Germans had declared it an open city to prevent it being damaged (the same courtesy had been extended by the French in 1940 - the result was that Paris was virtually completely unharmed during the war).

Southern France Invaded

On 15 August, a combined American and Free French force landed on the southern coast of France east of Marseilles. Meeting virtually no resistance, they pushed north along the valley of the Rhone River, making contact with the American troops in the north in mid-September. British troops seized Antwerp in early September and American troops entered German territory for the first time on 11 September 1944.

Germans Stand and Fight

The crossing into German territory served as a bolt to the German army: they turned and fought against the overwhelming odds, halting the Allied advance on the Meuse and lower Rhine rivers and on the German border with France. There the front would stalemate for several months.

In June 1944, the first of the German secret weapons, the V1 flying bomb, had started to fall on England; by September the first intercontinental ballistic missiles, the V2, had started falling on England as well. While there was some measure of defense against the V1 (it could be heard coming and it could be shot down or overturned by specially prepared and lightened British aircraft) there was no defense against the supersonic V2: its engine could only be heard after it had exploded on its target.

By November, the Germans had also deployed their first jet fighter squadrons: the ME 262 made mincemeat of all its opponents, from bombers through to fighters, and was absolutely invincible as nothing the Allies had was fast enough to shoot it down. It was however available in too few numbers to affect the outcome of the war.

The Warsaw Uprising

By July 1944, the Red Army had reached the Baltic coast near Riga and cut off the German Army Group North from the other German forces. Pushing westwards, the Red Army reached the Vistula River deep in Poland at the same time.

The closeness of the Red Army prompted the Polish resistance to launch an uprising in Warsaw against the Germans: this was suppressed after an uneven battle, although it is often claimed that the Red Army could have pushed on and invaded Warsaw if they wanted to. Why this was not done has never been satisfactorily answered. The Soviets argued that they were busy with offensives elsewhere: this was certainly true.

An offensive between the Carpathian Mountains and the Black Sea in August resulted in Rumania's surrender. Bulgaria followed suit in early September and Finland the same month. Soviet troops took the Yugoslavian capital Belgrade in mid-October. By November, the Soviet Army had reached Budapest in Hungary, where fanatical last ditch German and Hungarian resistance held them off for weeks.

Rome Falls

By May 1944, the Allies finally managed to break the German line at the famous Battle of Monte Casino (where a monastery had been reduced to rubble by Allied aircraft, ironically providing an ideal defensive position for the Germans who held off waves of successive attacks for months).

On 23 May, the besieged Allied troops at the Anzio beachhead finally managed to break out as the Germans withdrew: the Allies then entered Rome, an open city since June 4. After taking Ancona and Florence in August, the Allies were stopped by desperate German resistance for three months from overrunning all of Northern Italy.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea

In the Far East, the Allied island hopping continued: one after the other, Japanese strongholds fell, sometimes with horrendous costs to the Allies. Then the June 1944 Battle of the Philippine Sea saw the Japanese technological stagnation dramatically exposed.

On 19 June, in what was called the Marianas Turkey Shoot, advanced American aircraft shot down 219 of the now antiquated 326 Japanese aircraft sent against them. While the air battle was going on, American submarines sank all but one of Japan's remaining aircraft carriers: utterly defeated, the devastated Japanese navy limped back home with just 35 aircraft left. In the entire battle, the Americans lost 26 aircraft. Japanese technological stagnation as a result of being cut off from the White west, was the major cause for the scale of the defeat.

In October 1944, the Japanese were driven out of the Philippines: this saw the Japanese navy fighting its last major battle at the three day engagement known as the Battle for Leyte Gulf. The Japanese lost their last giant battleship in the Leyte Gulf and 25 other important ships: the Americans lost seven ships.

Bombers Over Japan

The American army captured the small but strategically vital islands of Saipan, Tinian and Guam by August 1944. From these islands, American B-29 bombers could reach Japan with ease: the regular bombing of Japan began in November 1944. It was from these island airfields that the decisive act of war against Japan would be launched, one that saved the American army from having to physically invade Japan itself: the atom bomb raids.

The Battle of the Bulge

In the west, the Germans launched one last offensive: taking advantage of bad weather which grounded the Allied airforce, a regrouped armored column attacked through the Ardennes forest on 16 December 1944. Taken by surprise, large numbers of Americans were captured: although a strong American pocket remained at the Belgian town of Bastogne which refused to surrender.

Despite making an 80 kilometer dent in the Allied lines (hence the name of the battle) the German effort was doomed after 23 December, when the bad weather broke and the Allied aircraft took to the skies, decimating the German land forces. The area captured by the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge was only finally retaken by the Allies at the end of January 1945, causing the advance into Germany to be postponed until February of that year.

Crossing the Rhine

To cross into Germany required the seizure of the all important bridges over the Rhine and Ruhr: to this end the Allies developed a plan to seize two bridges in southern Holland: one at Njimigen and the other at Arnhem. The first objective was reached, but the second was a disaster: the Allied paratroopers landed virtually on top of a Panzer division and were decimated, the survivors eventually escaping in dribs and drabs back to the Allied lines.

This, combined with the German offensive in the Ardennes, put off the final Allied invasion of German territory until 1945.

In February 1945, the first large American army crossed the Ruhr: in early March, American troops captured an intact bridge over the Rhine at Remagen. By the middle of March the Americans had occupied German territory east of the Rhine between Bonn and Koblenz and by the end of the month another American force had landed south of Mainz. The Ruhr industrial valley was encircled by American troops by the beginning of April; while British troops crossed the Weser River, halfway between the Rhine and the Elbe rivers, on 5 April. On 11 April, the Americans reached the Elbe near Magdeburg, only 120 kilometers from Berlin.

The Final Soviet Advance

By February 1945 the Red Army had driven the by now exhausted and shattered German forces to the Oder River, 60 kilometers from Berlin where Hitler had chosen to await the end, despite the existence of a much larger piece of German held territory in the south, centered around the Bavarian Alps.

Germany Crushed

In Italy, a renewed Allied offensive saw the Po River valley falling in April 1945; and on 16 April the Red Army began its drive on Berlin. On 20 April, the Americans captured Nuremberg, and by 24 April the Red Army had completely encircled Berlin, cutting it off from the rest of the shrinking Germany. On 25 April, the Soviet and American troops met up at Torgau on the Elbe River northeast of Leipzig, and Germany was split into two parts. By the end of April, virtually all German resistance in the west had collapsed: but in the east, the Germans fought even harder than before against the approaching Communists, exacting a toll of over 100,000 Soviet casualties in the Battle of Berlin.

Hitler Commits Suicide

When the German held part of Berlin was down to a few blocks in the center of the city, Hitler committed suicide by shooting himself on 30 April 1945. His body, and that of his long time girl friend and in the last day of their lives, his wife, Eva Braun (who had committed suicide by taking cyanide), was then burned to cinders in a shell hole in the garden of the chancellor' s office. Fragments of Hitler's skull were found by Soviet troops and were taken back to Moscow, where they are still held to this day in the Russian state archives, along with other personal effects belonging to the Nazi leader.

German Surrender

As his last official act, Hitler nominated the head of the German navy, Admiral Karl Doenitz, as his successor. Faced with a hopeless military situation, Doenitz organized an immediate surrender, which was signed on 7 May 1945. By then, the German forces in Italy had already surrendered, as had those in Holland, north Germany, and Denmark.

The Divine Wind

Japan also faced certain defeat by the time of Germany's surrender. Nonetheless, they refused to even consider giving up. Instead, hundreds of volunteers came forward to pilot the aging and otherwise useless Zero fighters as manned flying bombs to smash them into the approaching American invasion forces. These suicide pilots, known as kamikazes ("Divine Wind") were to inflict serious losses on the American forces before Japan's final surrender: for example, during the fighting for Luzon in the Philippines in January 1945, kamikaze pilots sunk 17 American warships and damaged a further 15.

Burma

At the height of their land invasion of Burma, Japanese troops had penetrated right to the eastern border of India itself. British troops then launched a counter attack: fighting under the most appalling conditions, often struggling with the jungle animals and disease as much as with the Japanese, the British soldiers in Burma slowly but surely fought the Japanese into a retreat. By the time of the end of the war, this "forgotten army" had virtually expelled the Japanese from Burma.

Fighting was often hand to hand: the British soldier's greatest fear was to be taken prisoner by the Japanese, who had a host of cruel tortures and slave labor prisoner of war camps set up: one of the more famous of these built a bridge over the River Kwai, the subject of which later became a book and famous film.

Iwo Jima and Okinawa

The first piece of Japanese territory proper was invaded on 19 February: the tiny barren island of Iwo Jima took three and a half weeks and 6,000 dead Americans before it was captured: the Japanese garrison resisted fanatically.

On 1 April, the second piece of Japanese land, Okinawa, was invaded. The northern part of the island was occupied in two weeks, but the Japanese resisted furiously in the south and were only finally subdued on 21 June. The lessons learned from Iwo Jima and Okinawa were not lost on the American Command: tiny pieces of land were defended literally to the last man, women and child.

On Iwo Jima, virtually no Japanese soldiers had been taken alive; on Okinawa hundreds of soldiers and civilians had jumped off cliffs rather than surrender. In addition, kamikaze planes had sunk 15 naval vessels and damaged 200 others off Okinawa alone. It had cost thousands of American lives to seize two minuscule pieces of territory: Japanese resistance would only get even more fanatical if the main Japanese islands were invaded.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

To save American lives, it was decided to attack Japan with the newly developed atom bomb and force it to surrender without a physical invasion. The first bomb was exploded in a test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on 16 July 1945, and two more bombs were built in quick order. The first was dropped over Hiroshima on 6 August, the other over Nagasaki on 9 August. The effect was devastating: in Hiroshima some 70,000 civilians died, and in Nagasaki, some 39,000 Japanese civilians died.

While these are staggering figures, perspective is put on the use of atomic bomb attacks on Japan by comparing them with the Allied fire bombing of the German city of Dresden. On one single night's bombing of the German city, a week before the war ended, 135,000 German civilians were killed: more than all the Japanese killed in both the atom bombings put together.

The Japanese Surrender

On 8 August, the stunned Japanese government found itself invaded in Manchuria by the Soviet Union: this was however a minor worry compared to the possibility of further atom bomb attacks. On 14 August, Japan announced its surrender. Unlike Germany, the terms of surrender were not unconditional: Japan was allowed to keep its emperor. Japan itself was placed under American occupation, with General Douglas MacArthur being appointed military governor.

The Nuremberg Trials

Once the war was over, the surviving leaders of Germany and Japan were put on trial by the Allies for what was called "War Crimes". While some of the charges were based on wartime atrocities committed by the accused - any atrocities committed by the victors were unsurprisingly ignored - the main defendants at Nuremberg faced the chief charge of "waging aggressive war."

Most of the defendants, who included Luftwaffe head Herman Goering, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Minister of Production Albert Speer, former Hitler deputy Rudolf Hess (who had been in British captivity since 1941 after flying off to a friend in Britain to try and make peace) and many general staff members, were all found guilty and sentenced to death or long periods of imprisonment.

The trials themselves broke many legal principles, most notably the principle of retrospectiveness: which holds that a person cannot be convicted of a crime if the act in question was not a crime at the time that it was committed.

In other words, if an act is declared illegal from date 10, then any acts similar to that committed before date 10 cannot be classed as crimes because the law declaring it illegal was not in existence at the time.

This was the case with the main charge of "waging aggressive war" - in 1939, there was no legal international precedent or law forbidding the "waging of war": if there was, every nation in the world would have been had up by an international court on this charge, as they all had waged war at some time or another.

The most shocking failure of the Nuremberg trials was however the inclusion of representatives of the Soviet Union on the panel of judges, rather than in the accused box. The Soviet Union had also "waged aggressive war" against Poland, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia before it was attacked by Germany. No mention was ever made of the Soviet attacks at the trials, and the inclusion of a Soviet judge on the bench made the entire process a mockery and clearly showed the trials up for what they were: an act of political revenge and nothing else.

Even in many of the atrocity charges there were glaring inconsistencies: the massacre of 11,000 Polish army officers at Katyn, carried out by members of the Soviet military, was pinned on the German door at the trials, with the Katyn massacre specifically included in the charge sheet against lower echelon German defendants.

The Nuremberg trials - and the Tokyo trials in which similar politically motivated charges were trumped up against the Japanese leaders - were a disgrace to the institution of international law.

Racial Implications of the War

The Second World War was yet another catastrophe for Europe with millions of people being killed directly or indirectly in the ultimately pointless conflict.

Direct Military Losses are estimated at the following:

| USSR | 13,000,000 |

| USA | 415,000 |

| Germany | 3,500,000 |

| Poland | 120,000 |

| Yugoslavia | 300,000 |

| Rumania | 200,000 |

| France | 250,000 |

| British Empire and Commonwealth | 452,000 |

| Italy | 330,000 |

| Hungary | 120,000 |

| Czechoslovakia | 10,000 |

In addition to these military losses, millions of civilians were killed, either in bombings, cross fire or starvation. Estimates of civilian losses by these means are put at:

| USSR | 5,000,000 |

| Germany | 3,740,000 |

| Poland | 200,000 |

| Yugoslavia | 300,000 |

| Rumania | 20,000 |

| France | 30,000 |

| British Empire and Commonwealth | 60,000 |

| Italy | 50,000 |

| Hungary | 40,000 |

| Czechoslovakia | 10,000 |

Finally Europe's Jewish population was badly dented by a deliberate Nazi policy of rounding then up and putting them into concentration camps.

German "black propaganda" - a fake 1944 stamp printed in Germany, almost the same as a British stamp then in circulation, only adjusted to replace the British king's head with that of Joseph Stalin, Soviet leader. The Communist and Star of David emblems were inserted as was the slogan : "This is a Jewsh War". The word "Jewsh" was deliberately misspelled to lay emphasis on the words '"Jews". The stamps were then circulated into British society through sympathizers in an attempt to spread propaganda.

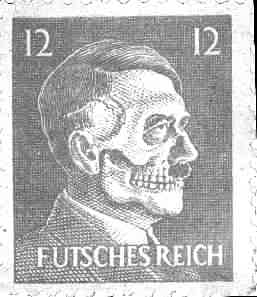

British "black propaganda" - a parody stamp produced by the British and circulated in Germany, depicting Hitler's head as a death head.

The effect of the Jewish factor was a primary reason for the outbreak of the war and lay behind much of the Allies' double standards when reacting to German and Soviet aggression at the beginning of the war. For this reason it is first necessary to look at the position of the European Jews in some detail before discussing the German state itself: this is done in the following chapter.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.