Here's a tip to thieves: If you are bent on stealing packages of Gillette Mach3 razor blades, go someplace other than Tesco's Newmarket Road store in Cambridge, England. There, a "smart shelf" continuously queries tiny radio chips embedded in the packages it holds, and senses the silence when one is removed. The system may soon be programmed to alert security when several are taken at once, Greg Sage, a Tesco spokesman, said.

And, yes, Procter & Gamble will notice if a case of Pantene shampoo does not make it to the Wal-mart Supercenter in Broken Arrow, Okla. Its truck is equipped to monitor signals continuously from chips hidden in each case. If any case stops sending its "Hi, I'm still here" signal, a monitor in the "smart truck" will record exactly when and where.

|

|

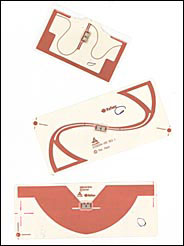

Tiny chips attached to packages of razor blades can send messages to store managers, alerting them when shelves are depleted. |

Such technology, known as radio-frequency identification — the same techniques that enable an electronic sensor to record data from an E-ZPass tag or an office door to open for people with chip-equipped cards in their pockets — could one day stymie pilferers. But it is also capable of doing much more for commerce. Beyond Gillette and Procter & Gamble, companies as diverse as International Paper and Canon USA are teaming up with retailers and customers to apply R.F.I.D., as it is known, to tracking products from the time they leave an assembly line to the time they leave the store.

The companies are tagging clothes, drugs, auto parts, copy machines and even mail with chips laden with information about content, origin and destination. They are also equipping shelves, doors and walls with sensors that can record that data when the products are near. "We want to track all of our merchandise, and that includes items that people are unlikely to steal," William C. Wertz, a spokesman for Wal-Mart Stores, said.

Chip manufacturers are busily spreading that gospel. "That need to have the right product on the right shelf in the right store at the right time — ultimately, that's what will drive our business," said Karsten Ottenberg, a senior vice president at Philips Semiconductor, the leading maker of radio frequency chips and a unit of Royal Philips Electronics.

|

|

Toby Wales for The New York Times

Radio-frequency identification chips, like the three shown above, can track an item from the time it is assembled to the time it is sold. They now cost about 30 cents each, but prices are expected to fall sharply. |

Early tests are encouraging. For three months in 2001, Gap tested radio frequency tags on denim clothes at a store in Atlanta. Sales jumped because the tags prevented the store from running out of popular items, and the tags made it quicker to find any items in stock.

Typically, 15 percent of shoppers leave clothing stores without getting what they want; during the test, fewer than 1 percent of Gap shoppers left empty-handed.

Radio frequency identification still has too many kinks, however, to be an immediate panacea for retailers. Cordless phones, two-way radios, local wireless networks and other communications devices that are widely deployed in factories, warehouses and stores can interfere with the signals. And, although radio tag readers can, under ideal conditions, identify well over 100 tagged items every second from quite a distance, radio waves have a hard time penetrating metals and liquids — something that Procter & Gamble is addressing with the Pantene test.

And costs are still prohibitive. The electronic tags cost at least 30 cents apiece; most experts think anything above 5 cents is too expensive to be widely used for individual packaged goods. Prices would have to fall to less than a penny for virtually everything in stores to be tagged. Sensors, which can be either hand-held or built into walls, can cost $1,000 each.

But costs are coming down fast. Alien Technology, for one, says that it can now sell radio frequency identification tags profitably at 5 cents each for orders of a billion tags or more. Just last month, Gillette said it would buy up to 500 million tags over the next few years from Alien.

But Alien's manufacturing capacity is currently just a small fraction of what it would need to fill orders over a billion quickly. And experts warn that while the silicon chips continue to shrink in size and fall in price, making the attached antennas small enough and cheap enough is much harder.

Moreover, most retailers say they are reluctant to invest in the technology until product tags are universally readable, as bar codes are today. That means that every retailer, manufacturer and carrier must agree to standards, and use tags and sensors that speak the same language.

"It's one thing to say something is a great technology, but quite another to say that you're ready to scrap existing systems to accommodate it," said Daniel Butler, vice president for retail operations at the National Retail Federation, a trade association based in Washington.

Consumer privacy is also an issue. It would be easy to combine credit card data with information from the retail chips to know who bought what, and when — and, conceivably, track the product even after it left the store.

"I don't think the average consumer understands the threat to personal privacy that these kinds of technologies can present," said Alan N. Sutin, a partner specializing in information technology at the law firm of Greenberg Traurig.

William H. Steele, a consumer products analyst with Bank of America, doubts companies will "succumb to the temptation to keep tracking products in the consumers' hands," but he, too, stops short of calling the issue specious. "There should be a certain level of skepticism on the part of the U.S. consumer," he said.

Still, companies are increasingly viewing the identification technology as a potential savior. In 1999, Gillette, Procter & Gamble and the Uniform Code Council, which administers bar code standardization, founded the Auto-ID Center at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to be a standards and research clearinghouse. The center has satellite labs at Cambridge University in England, and in Japan and Australia.

The technological limitations of bar codes makes the growing interest in R.F.I.D. easy to understand. Kevin Ashton, a P.& G. executive who directs the Auto-ID Center, estimates that on average 10 percent of stores are out of items the managers think are in stock — and as many as 40 percent do not realize they are out of a color or size.

The monetary impact of losing track of goods is huge. According to a survey by the University of Florida, shrinkage — the common retailing term for goods that disappear either through theft, misplacement, fraud or just bad record keeping — cost retailers a record $31.3 billion last year. Only a third was a result of shoplifting. Nearly half was employee theft, about 5 percent was vendor theft and 15 percent was paperwork errors.

Suppliers have as much at stake as retailers. Colin Peacock, the leader of a Gillette task force to study shelf availability, said that 73 percent of customers left a store if Mach3 blades were out of stock; 27 percent bought a competitor's blades. He said Mach3 sales had gone up 288 percent at the Cambridge Tesco store that had the smart shelf.

Stores often resort to putting frequently pilfered items behind glass or behind counters. That means customers must wait for a clerk to get the products. The practice drives away impatient shoppers and all but eliminates impulse buys.

Mr. Peacock suspects that sales are halved when products are hidden away. "The impact of such defensive merchandising can be worse than the problems it solves," he said.

Once it is perfected, radio frequency technology may solve not just those problems, but some that are unrelated to stocking issues. Because the tags, unlike bar codes, are programmable chips, a store like Wal-Mart that frequently changes prices can attach the price to the item and know exactly what a consumer paid if the item is returned — even if the customer lost the receipt.

And then there are product recalls to consider. Radio frequency technology could pinpoint a tainted batch, and — if customers paid with credit cards or used store discount cards — identify customers who purchased such items.

"It would be wonderful to be able to spot just those items that came from a plant that has a flaw, or those perishable items that took too long to arrive and thus might spoil sooner," Mr. Wertz of Wal-Mart said.

Canon USA wants to deploy radio frequency identification to track machines at locations that use dozens of printers and copiers. "It would help us schedule preventive maintenance, and alert us to get equipment back when the lease expires," said James J. Gordon Jr., Canon's vice president for logistics.

Even the United States Postal Service has gotten into the act. Last month, it promoted Charles E. Bravo, until then its chief technology officer, to the new job of senior vice president for intelligent mail and address quality, and charged him with studying tracking technologies.

"We'd love to be able to tell a company that a customer's check is truly in the mail, or that its direct mail flier was just delivered to a customer's door," Mr. Bravo said.

And imagine if the company can also be sure that the item the flier is advertising will be available.

"Increasing productivity, lowering inventories, decreasing theft, all are important," said Paul J. Rieger, Procter & Gamble's associate director of supply chain innovation. "But ending out-of-stock situations, that is still our biggest goal."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company