October 23, 2002

By RONALD POWERS, Associated Press Writer

WASHINGTON

Richard Helms, the spymaster who led the CIA through some of its most difficult years and was later fired by President Nixon when he refused to block an FBI probe into the Watergate scandal, is dead. He was 89.

Helms, the quintessential CIA man who was an efficient bureaucrat and faced easily into the background, died Tuesday night at his home, the CIA said. No immediate cause of death was given. The tall and lean Helms, a tennis enthusiast, was no dashing, swashbuckling spook. Rather, he was an elusive, laconic and reserved man who willingly took marching orders from whomever occupied the Oval Office. He was a master of playing by the rules of the game as he understood them at the time.

"The United States has lost a great patriot," CIA Director George J. Tenet in a statement Wednesday. "The men and women of American intelligence have lost a great teacher and a true friend."

"To the very end of his life, Ambassador Helms shared his time and wisdom with those who followed him in the calling of intelligence in defense of liberty," Tenet said. "His enthusiasm for this vital work, and his concern for those who conducted it, never faltered."

After a brief stint in journalism - his early ambition had been to one day own a newspaper - Helms began his spying career during World War II with the Office of Strategic Services. He was well entrenched in America's nascent spy establishment when the OSS became the Central Intelligence Agency and he served in the agency's highest ranks from the start.

He had a remarkable career in spying's murky underworld, believed deeply in the CIA's mission and was one of its biggest boosters.

"Let's face it," he once said, "the American people want an effective, strong intelligence operation. They just don't want to hear too much about it."

Helms rose steadily through the ranks and in 1965 became deputy director. In June 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated him to become CIA director. He was the first career spy to head the agency.

By the time he took over, however, many Americans were growing skeptical of their government and "intelligence" was beginning to take on a dark connotation, something that Helms, who with his Cold War mindset, seemed to never fully understand.

But Helms had himself played a critical role in many of the CIA's most controversial and troubling operations, from plotting the assassinations of foreign leaders such as Fidel Castro to overthrowing the Marxist government of Chilean President Salvador Allende Gossens.

After studiously living most of his life out of the public eye, Helms would come to see his name linked to many of his agency's most nefarious abuses, embarrassments and illegal activities.

First for Johnson and later under President Richard Nixon, Helms headed Operation Chaos, which spied on, poked into and disrupted the private lives of U.S. citizens as the CIA improperly investigated whether the increasingly energetic and powerful anti-Vietnam War movement had links to foreign countries.

Under Nixon, the CIA's role in domestic spying hovered on the extreme edge of the agency's charter and at times crossed over into activities that were clearly illegal, author Thomas Powers wrote in his authoritative 1979 book about Helms, "The Man Who Kept the Secrets."

Nixon's purpose was clear, Powers said: "He wanted to know what his domestic opponents were up to so that he might anticipate, harass, frustrate, and discredit them."

And it wasn't long before Helms found the CIA sucked into the Watergate abyss.

The bumbling burglars who broke into the Democratic Party's offices had worked for his agency. Then Nixon tried to enlist Helms' help in blocking the FBI's investigation. When he refused to cooperate, Nixon gave the veteran spy the boot and sent Helms packing to Tehran where he served as ambassador to Iran.

Over the next few years, however, Helms was repeatedly called back to Washington to testify before congressional committees investigating the CIA's assassination schemes, its role in Chile and its spy operations within the United States, something the agency's charter barred it from doing.

By the mid-1970s it had become clear that Helms had intentionally misled Senate committees investigating the agency. In 1976, with the Justice Department probing his CIA tenure, he quit his ambassadorship.

Helms defended his testimony by maintaining that his mission was to protect intelligence secrets and that he'd not been obliged to tell the truth to Senate committees that held no CIA oversight power.

"I felt obliged to keep some of this stuff, in other words, not volunteer a good deal of information," Helms told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1975.

Federal prosecutors refused to buy into Helms' explanation and announced a year later they would seek to indict him for perjury.

Helms responded aggressively, saying he was prepared to play hardball, go to trial and publicly revel matters the government wanted to remain untold.

The Justice Department took Helms' bluff seriously and backed down.

In the end, prosecutors offered Helms a plea bargain in which he pleaded no contest to charges he'd failed to answer the Senate's questions "fully, completely and accurately." He paid a $2,000 fine and received a suspended two-year prison sentence.

Helms considered the criminal conviction a "badge of honor."

"I don't feel disgraced at all," he told reporters gathered on the courthouse steps after his plea. "I think if I had done anything else I would have been disgraced."

Richard McGarrah Helms was born March 30, 1913, in St. Davids, Pa., into a family of some means. His father was a corporate executive and his maternal grandfather, Gates McGarrah, was a leading international banker.

Helms grew up in South Orange, N.J., and spent two of his high school years in Europe, leaning French, German and the social graces.

He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Williams College in 1935, where he served as the editor of the school newspaper and yearbook. He was voted "most likely to succeed" and "most respected."

Out of college, he returned to Europe as a cub reporter for United Press and gained some notice for his exclusive interview with Adolf Hitler.

By 1937 he was back in the states and working as the national advertising manager for The Indianapolis Times, a now-defunct newspaper.

During the Second World War, he was assigned to the OSS, because of his knowledge of foreign languages and remained with the intelligence service, which became the CIA in 1947.

Helms' first marriage ended in divorce and he later married the former

Cynthia McKelvie.

Obituary

Richard M. Helms Dies at 89; Dashing Ex-Chief of the C.I.A.

By CHRISTOPHER MARQUISWASHINGTON Oct. 23 — Richard Helms, a former director of central intelligence who defiantly guarded some of the darkest secrets of the cold war, died today of multiple myeloma. He was 89.

An urbane and dashing spymaster, Mr. Helms began his career with a reputation as a truth-teller and became a favorite of lawmakers in the late 1960's and early 70's.

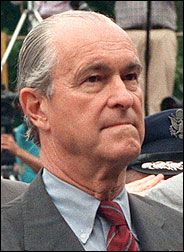

Associated Press

Richard M. Helms, a former director of central intelligence who defiantly guarded some of the darkest secrets of the cold war, died today. | ||||

But he eventually ran afoul of Congressional investigators who found that he had lied or withheld information about the United States' role in assassination attempts in Cuba, anti-government activities in Chile and the illegal surveillance of journalists in the United States.

Mr. Helms pleaded no contest in 1977 to two misdemeanor counts of failing to testify fully four years earlier to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. His conviction, which resulted in a suspended sentence and a $2,000 fine, became a rallying point for critics of the Central Intelligence Agency who accused it of dirty tricks, as well as for the agency's defenders, who hailed Mr. Helms for refusing to compromise sensitive information.

In the title of his 1979 biography of Mr. Helms, Thomas Powers called him "The Man Who Kept the Secrets." Mr. Helms's memoir, "A Look Over My Shoulder: a Life in the C.I.A.," is scheduled to be released in the spring by Random House.

After he left the C.I.A. in 1973, Mr. Helms served until 1977 as the American ambassador to Iran under Shah Mohammed Riza Pahlevi, who was supported by the United States. He later became an international consultant, specializing in trade with the Middle East.

Born on March 30, 1913, in St. Davids, Pa., Richard McGarrah Helms — he avoided using the middle name — was the son of an Alcoa executive and the grandson of a leading international banker, Gates McGarrah. He grew up in South Orange, N. J., and studied for two years during high school in Switzerland, where he became conversant in French and German.

At Williams College, Mr. Helms excelled as a student and leader. He was class president, editor of the school newspaper and the yearbook, and was president of the senior honor society. He fancied a career in journalism, and went to Europe as a reporter for United Press. His biggest scoop, he said, was an exclusive interview with Adolf Hitler.

In 1939 he married Julia Bretzman Shields, and they had a son, Dennis, who became a lawyer. The couple were divorced in 1968, and Mr. Helms married Cynthia McKelvie later that year.

When World War II broke out, Mr. Helms was called into service by the Naval Reserve and because of his linguistic abilities was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the C.I.A. He worked in New York plotting the positions of German submarines in the western Atlantic.

From the beginning, he worked in the agency's covert operations, or "plans" division, and by the early 1950's he was serving as deputy to the head of clandestine services, Frank Wisner.

In that capacity, in 1955, Mr. Helms impressed his superiors by supervising the secret digging of a 500-yard tunnel from West Berlin to East Berlin to tap the main Soviet telephone lines between Moscow and East Berlin.

For more than 11 months, until the tunnel was detected by the Soviet Union, the C.I.A. was able to eavesdrop on Moscow's conversations with officials in East Germany and Poland.

Over the next 20 years, Mr. Helms rose through the agency's ranks, and in 1966 he became the first career official to head the C.I.A. He served under such men as Allen W. Dulles, Richard M. Bissell, John A. McCone and Vice Adm. William F. Raborn.

During most of his tenure as C.I.A. chief, Mr. Helms received favorable, occasionally fawning attention from lawmakers and the press, who remarked on his professionalism, candor, and even his dark good looks.

That reputation grew in 1973, when Mr. Helms clashed with President Nixon, who sought his help in thwarting an F.B.I. investigation into the Watergate breakin. When Mr. Helms refused, according to the Powers book, Mr. Nixon forced him out and sent him to Iran as ambassador. But Mr. Helms soon found himself called to account for his own actions when the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence delved into the agency's efforts to assassinate world leaders or destablize socialist governments.

The committee, which was led by Senator Frank Church, an Idaho Democrat, accused Mr. Helms of failing to inform his own superiors of efforts to kill Fidel Castro of Cuba, which the Senate panel called "a grave error in judgment."< A separate inquiry by the Rockefeller Commission also faulted Mr. Helms for poor judgment for destroying documents and tape recordings that might have assisted Watergate investigators.

But the most contentious criticism of Mr. Helms centered on Chile. In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Mr. Helms insisted that the C.I.A. had never tried to overthrow the government of President Salvador Allende Gossens or funneled money to political enemies of the Marxist leader.

Senate investigators later discovered that the C.I.A. had run a major secret operation in Chile that gave more than $8 million to the opponents of Mr. Allende, using the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation as a conduit. Mr. Allende died in a 1973 military coup, which was followed by more than 16 years of military dictatorship.

Mr. Helms was forced out of the agency in 1973 by President Nixon, who considered him insufficiently cooperative in providing C.I.A. support to the Watergate cover-up, although the agency had been criticized in Congress and in the press for having been too cozy with Nixon aides in their quest to silence or destroy political enemies.

Mr. Nixon appointed him ambassador to Iran, a post in which Mr. Helms served until 1977, when he returned to Washington to plead no contest to charges that in 1973 he had lied to a Congressional committee about the intelligence agency's role in bringing down the Allende government.

"I had found myself in a position of conflict," he told a Federal judge at the formal proceeding on his plea bargain with the Justice Department. "I had sworn my oath to protect certain secrets.

"I didn't want to lie. I didn't want to mislead the Senate. I was simply trying to find my way through a difficult situation in which I found myself."

"You now stand before this court in disgrace and shame," the judge told him, and sentenced him to two years in prison and a $2,000 fine. The prison term was suspended.

Mr. Helms said outside the courtroom that he wore his conviction "like a badge of honor," and added: "I don't feel disgraced at all. I think if I had done anything else I would have been disgraced."

Later that day he went to a reunion of former C.I.A. colleagues, who gave him a standing, cheering ovation, then passed the hat and raised the $2,000 for his fine.

For a man who considered himself a genuine patriot, it was a bleak note on which to end his professional career. Mr. Helms believed he had performed well in a job that, although many Americans considered it sinister and undemocratic, was nevertheless a cold-blooded necessity in an era of cold war.

Mr. Helms, who was allowed to receive his government pension, put his intelligence experience to use after his retirement. He became a consultant to businesses that made investments in other countries.

He was known as a charming conversationalist, a gregarious partygoer and an accomplished dancer, and he and his wife continued to be familiar figures on the capital party scene.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Helms is survived by a son, Dennis Helms, of Princeton, N.J.