The freight train rumbled to an agonizing stop on

the rails inside of the Auschwitz compound. The human cargo that

was packed tightly into its bevy of cattle cars continued to groan

and clamor, suffering as they were from a four-day journey without

food, water, bathroom facilities, or even fresh air. The Jewish

prisoners were the latest victims of the Nazi campaign to

liquidate the Jewish population of Hungary, the last Jewish

community to remain intact during the war. Their final destination

was the violent, Dantesque nightmare of Auschwitz, the premier

Nazi death factory in southwestern Poland, the most efficient cog

in the wheel of the Nazi’s Endlosung, Final Solution, to the

so-called Jewish question.

The doors of each cattle car were violently thrown

open by Nazi SS soldiers carrying machine guns. "Raus,

raus!" ("Out, out!") they screamed at the frightened and

bewildered Jews, who hurried out the doors under a rain of cudgel

blows and past the snapping, barking jaws of the camp’s German

Shepherds. The air was thick with the deafening and confusing

sound of orders being screamed, dogs barking, and the stench of

burning flesh and hair that spewed from the smokestacks of the

camp’s 5 crematoria 24 hours a day. Families were separated

immediately, with the males forming one line and the females

forming another. Most victims were unaware that this was the last

time that they would see their loved ones alive, unaware of their

lost opportunity to say last good-byes.

The SS troops marched the doomed prisoners to the

head of the ramp onto which they had exited. They were led before

an SS officer who, in the midst of all the madness, agony and

death, seemed very out of place. His handsome face was set with a

kind smile, his uniform impeccably tailored, cleaned and pressed.

He was cheerfully whistling an opera tune, one of his favorites by

Wagner. His eyes betrayed nothing but a cursory interest in the

drama that was unfolding before him, the drama of which he alone

was the chief architect. He carried a riding crop, but rather than

using it to strike the prisoners as they passed before him, he

merely used it to indicate which direction he selected them to go

in, links oder rechts, left or right. Unbeknownst to the

prisoners, this charming and handsome officer with the innocuous

demeanor was engaging in his favorite activity at Auschwitz,

selecting which new arrivals were fit to work and which ones

should be sent immediately to the gas chambers and crematorium.

Those sent to the left, roughly 10 to 30 percent of all new

arrivals, had their lives spared, at least for the moment. Those

sent to the right, usually 70 to 90 percent of all new arrivals,

had been condemned to die without even a passing glance from their

judge and jury at Auschwitz. The handsome officer who held

omnipotent sway over the fate of all the camp’s prisoners was Dr.

Josef Mengele, the Angel of Death.

|

|

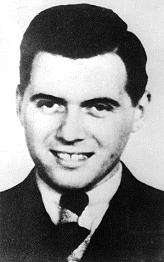

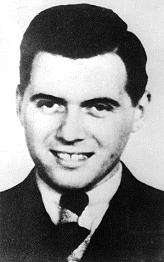

Josef Mengele at Auschwitz in

1943 |

Contents

The Mengeles of Gunzburg

Josef Mengele was

the eldest of three sons born to Karl and Walburga Mengele in the

Bavarian village of Gunzburg. Karl was a local industrialist who

owned a plant that manufactured farming equipment. He was known as

a stern but fair employer and a hard worker. It was his wife

Walburga, however, whom his employees feared the most. An immense

woman with a terrible temper, she was often known to storm onto

the floor of her husband’s factory and publicly chastise

individual employees for laziness and poor workmanship. Warnings

were hurriedly passed down the production line whenever Walburga

was seen approaching the factory, and workers scrambled to stay

clear of her wrath.

Walburga ruled her home with an equal amount of firmness,

demanding respect and obedience from her three sons, Josef, Alois,

and Karl, Jr. A devout Catholic, Walburga saw to it that her boys

strictly practiced the faith of the Church. She was equally as

cold and demanding in her relationship with her husband, Karl. One

afternoon, Karl arrived home in a new automobile he had purchased

in order to celebrate the growing success of his factory. However,

instead of thrilling and impressing his wife with this purchase,

Karl was greeted with spiteful admonishments for having so

foolishly spent money on something as frivolous as a car without

first consulting with her. It was a moment that exemplified the

extent to which Walburga sought total control over her household

and the lives of those who lived in it.

It is clear from his memoirs that his mother’s behavior and the

relationship she shared with Karl left a lasting impression on

young Josef. He describes his father as a cold man, distant and

preoccupied with his work at the factory. Walburga is described as

someone incapable of loving. While she may have indeed been able

to mold a disciplined, respectful son in Josef, her cold-hearted

methods may well have contributed to her son’s capacity for murder

and bloodlust as an SS doctor at Auschwitz.

|

|

Josef as a

young man (Corbis) |

Despite

the lack of love and affection in his home, young Josef is

remembered as a bright, cheerful boy in Gunzburg. Peers and adults

alike greeted him as "Beppo," an affectionate nickname for the

handsome, engaging young child. While never the top student in his

classes, Josef nevertheless did well, and was recognized as a

bright, ambitious student. He was the model of a well-behaved

student, earning verbal compliments from his otherwise strict

teachers, and high marks for conduct and punctuality.

As Beppo matured into adolescence, he continued to refine his

social skills, becoming a strikingly handsome young man. Mengele

is remembered as someone who exuded a natural self-confidence, a

charming and articulate speaker who was much sought after by the

village’s young women. His perfectly-styled dark hair, the

carefree light in his eyes, and his winsome smile, combined with

his extraordinary social graces, imbued Mengele with a

Kennedyesque charisma. It was at this early age that Mengele

acquired the habit of dressing exclusively in hand-tailored

clothing and sporting what would become his trademark, white

cotton dress gloves, gloves that have been used by Auschwitz

survivors to distinguish him from other SS doctors.

It was during this period that Josef and his ambition came into

direct conflict with the wishes of his father, Karl. Josef’s

father wished for his eldest son to work for the family factory in

Gunzgburg, perhaps as an accountant. However, young Josef dreamt

of a career far beyond the confining realm of business, and far

beyond the boundaries of his provincial Bavarian home. Throughout

his youth Josef dreamt of leaving Gunzburg and pursuing a career

in science and anthropology. Making no secret of the scope of his

ambitions, Josef once prophetically boasted to a friend that his

name would one day appear in the encyclopedia. In 1930 Josef

graduated from the Gunzburg gymnasium, or high school, and

passed his Abitur, the preliminary college entry

examination. While his score was unremarkable, it was good enough

for him to be accepted to the University of Munich. Munich is the

Capital of Bavaria, and at the time was the heart of the growing

National Socialist movement, and led by a political revolutionary

named Adolf Hitler.

Contents

The Making of A Young Nazi

Josef Mengele

left Gunzburg for Munich in October of 1930 to begin his studies

at Munich University. He enrolled as a student of Philosophy and

Medicine, degrees that would ultimately lead his career path to

the Heart of Darkness, Auschwitz. At the same time that young

Mengele was beginning his studies, the City of Munich was in the

throes of an ideological revolution. In 1930 the Nazis were the

second-largest party in the German parliament. Adolf Hitler used

Munich as the primary stage from which he would achieve domination

over all of German society. His hateful, frenzied, nationalistic

speeches incited his Bavarian audiences, and intoxicated them with

visions of a new German Empire populated by the German

Super-Race.

Mengele had remained apolitical up until this point in his

life. He was satisfied in his pursuit of life’s leisure pleasures.

His quest for success and renown was confined to the realm of

anthropology and academia. However, he easily succumbed to the

contagious Nazi hysteria that swept up so many of his peers. In

his memoirs he wrote:

My political leanings were, I think for reasons of family

tradition, national conservative. I had not joined any political

organization. But in the long run it was impossible to stand aside

in these politically stirring times, should our Fatherland not

succumb to the Marxist-Bolshevik attack. This simple political

concept finally became the decisive factor in my life.

This "political concept" that Mengele wrote of became his

vehicle upon which he would seek to advance his career, his fame

as a researcher and scientist. Wasting no time, he joined a

nationalistic organization called the Stalhelm, or the

Steel Helmets, in 1931. The Stalhelm wore decorative German

uniforms and paraded to nationalist music during public events.

While they were not yet affiliated with the Nazi Party at this

time, they nonetheless shared the same rabid nationalistic

ideology as the Nazis.

As his political consciousness began to blossom, Mengele

commenced his studies, focusing on anthropology and paleontology,

as well as medicine. Medicine, or the art of healing, was truly a

secondary interest of Mengele’s; his growing passion was for

eugenics, the search for the keys to unlock the secret of genetics

and reveal the sources of human deformities and imperfections.

Mengele’s interest in this field of study arose at a time when a

number of prominent German academics and medical professionals

were espousing the theory of "unworthy life," a theory which

advanced the notion that some lives were simply not worthy of

living. It was here that Mengele began to strive in his efforts to

distinguish himself, to both gain renown and respect as a

scientific researcher and to advance the perfection of the German

race. However ambitious Mengele may have been in this regard, his

academic passion revealed little to nothing of the murderous zeal

that was to one day result from it. One of his university

colleagues, Professor Hans Grebe, has stated that "There was

nothing in his personality to suggest that he would do what he did

(as an SS doctor at Auschwitz)"

If Mengele himself became a cold-blooded monster at the height

of his Nazi career, he certainly learned at the feet of some of

Germany’s most diabolical minds. As a student Mengele attended the

lectures of Dr. Ernst Rudin, who posited not only that there were

some lives not worth living, but that doctors had a

responsibility to destroy such life and remove it from the general

population. His prominent views gained the attention of Hitler

himself, and Rudin was drafted to assist in composing the Law for

the Protection of Heredity Health, which passed in 1933, the same

year that the Nazis took complete control of the German

government. This unapologetic Social Darwinist contributed to the

Nazi decree that called for the sterilization of those

demonstrating the following flaws, lest they reproduce and further

contaminate the German gene pool: feeblemindedness; schizophrenia;

manic depression; epilepsy; hereditary blindness; deafness;

physical deformities; Huntington’s disease; and alcoholism.

In 1934, Hitler ordered the SA, or Brownshirts, to absorb the

Stalhelm organization, automatically making Mengele a member.

However, a kidney ailment which left him in a weakened condition,

forced him to resign from the organization. He was now free to

devote all of his time to his studies. Five years after entering

the University, Mengele was awarded a Ph.D. for his thesis

entitled "Racial Morphological Research on the Lower Jaw Section

of Four Racial Groups." Through rather dry scientific prose

Mengele postulated that it was possible to detect and identify

different racial groups by studying the jaw. While devoid of any

racist (specifically anti-Semitic) overtones, Mengele’s argument

paralleled those made by others who claimed that physical

characteristics such as the jawbone or the shape of one’s nose

could be used to determine if someone was Jewish. In 1936 Mengele

passed his state medical examination and began working in Leipzig

at the university medical clinic.

The next year, 1937, proved to be a turning point for both

Mengele’s career and the history of the Holocaust itself. He was

recommended for and received a position as a research assistant

with the Third Reich Institute for Hereditary, Biology and Racial

Purity at the University of Frankfort. He was assigned to work for

Professor Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, one of the premier minds

in the field of genetics. Von Verschuer was a public supporter of

Hitler’s, praising him for "being the first statesman to recognize

hereditary biological and race hygiene." Mengele quickly applied

himself in his unabashed pursuit of von Verschuer’s praise and

approval, which he quickly acquired. In von Verschuer Mengele had

found the parental adulation and affirmation so sorely missing

from his childhood. As von Verschuer provided Mengele with that

for which he had longed for all his life, Mengele returned the

gesture with an unbending willingness to please his mentor.

The two streams of ambition that had come to define Mengele’s

life, becoming a renowned scientist and a genetic purifier, had

found unity within the Nazi movement. He became an official Party

member in 1937. In May of 1938 he applied for membership with and

was accepted into the Schutzstaffel, or SS. This was Hitler’s

elite corps of race guardians, those who demonstrated both the

purist Aryan racial background and adherence to Nazi ideology and

practices. By the age of 28, Mengele had climbed to a place of

prominence within the Nazi hierarchy and was positioned to wield

great power and influence.

|

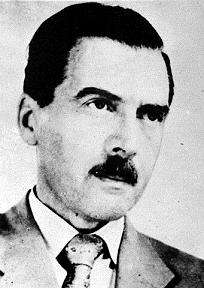

Mengele conducting "racial purity"

interviews

in 1940 with an elderly Polish couple

|

This same year, Frankfort University awarded Mengele his

medical degree. It was also in 1938 that he received his first

experience in military training, spending three months training

for combat with the Wehrmacht, or German Army. For the

rest of 1938 until 1940 Mengele remained with the Institute,

assisting von Verschuer and reviewing the work of other

researchers. In 1939 war broke out, and Mengele was electrified

with the hope of fighting for Father Germany. He was not

disappointed; although he had to wait until June of 1940 due to

his prior kidney ailment, he was accepted to the Waffen SS, elite

soldiers within the SS itself, and the most fanatical adherents to

Hitler’s call to preserve and protect the German race.

Mengele continued to distinguish himself, this time as a

soldier. As a lieutenant, he was awarded the Iron Cross Second

Class in June of 1941 on the Ukrainian Front. In January of 1942,

while serving with the SS Viking Division deep behind Soviet

lines, he pulled two German soldiers from a burning tank, and was

awarded the Iron Cross First Class, as well as the Black Badge for

the Wounded and the Medal for the Care of the German People.

Wounds he received during this second campaign prevented Mengele

from returning to combat. Instead, he was posted at the Race and

Resettlement Office in Berlin, where he was also promoted to the

rank of captain. By this time his mentor, Professor von Verschuer,

was also stationed in Berlin at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for

Anthropology, Human Hereditary Teaching and Genetics. A prominent

Nazi scientist such as von Verschuer certainly had first-hand

knowledge of the Final Solution policy that had recently been

formalized in Berlin by the top members of the Nazi hierarchy. He

would have also correspondingly been aware of Nazi plans to

construct enormous concentration camps across Europe, and that

such camps held untold opportunities for in vivo

experiments, living genetic research to be conducted on human

subjects. Within a year after being posted to Berlin, Dr. Josef

Mengele received a new assignment. In May of 1943, Mengele

departed from Berlin for his next assignment: the Nazi

concentration camp at Auschwitz, Poland.

|

|

Josef as a Waffen SS officer in

1942 |

Contents

Auschwitz

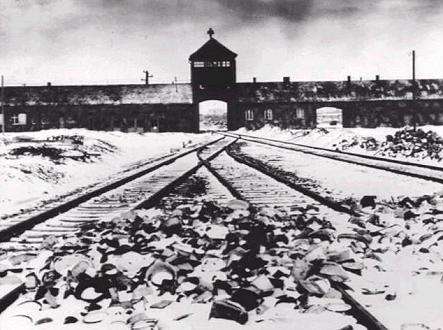

|

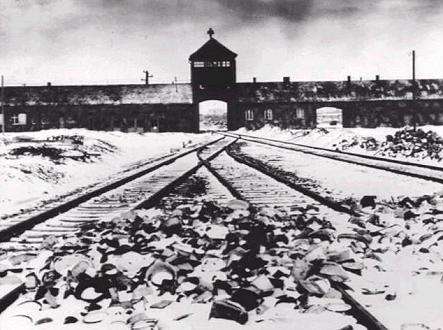

|

The 'Gate of Death' at Auschwitz |

The death factory at Auschwitz was a gruesome kingdom of human misery. Barracks and

their inhabitants were inundated with the foulest of sanitary conditions. Diseases such as

typhus and diarrhea were rampant, as were lice, vermin and fleas. It was over this kingdom

which Dr. Josef Mengele sought to preside. Mengele’s stated mission at Auschwitz was

to perform research on human genetics. His work was funded through a grant that Professor

von Verschuer had secured through the German Research Council in August of 1943. The goal

of Mengele’s work was to unlock the secrets of genetic engineering, and to devise

methods for eradicating inferior gene strands from the human population as a means to

creating a Germanic super-race. However, despite the scientific premise for his work,

Mengele’s accomplishments added volumes to the annals of human cruelty while

contributing nothing of value to the greater understanding of human genetics and genetic

engineering.

Mengele set out to immediately distinguish himself from the other SS doctors at

Auschwitz. He already stood apart as the only doctor in the camp to have been decorated

for his conduct in battle. Mengele made certain to festoon his impeccable SS uniform with

the medals he had been awarded. He often made reference to his experiences on the front,

and was obviously very proud and protective of his medals. But it was not merely his

military background which would come to distinguish Mengele from his colleagues, but his

obsessed devotion to his work at Auschwitz that established his reputation as a ruthless,

cold-blooded killer whose name inspired fear even in other SS officers. He immediately

demonstrated a deep capacity for wanton murder during a typhus epidemic that broke out in

the camp just days after he had arrived. He ordered a thousand Gypsy men and women who had

the disease to the gas chambers, while sparing the lives of German Gypsies. The

significance of this incident is twofold: Mengele adhered to the Nazi belief that Gypsies

were a subspecies of the human race, and therefore were "unworthy life".

However, the fact that he spared the lives of German Gypsies, at least in this instance,

may have resulted from the fact that Mengele himself had many Gypsy aspects to his own

physical appearance, from his tawny skin to his dark hair and eyes. He did not at all

resemble the ideal Nazi Aryan with blonde hair and blue eyes. At any rate, his willingness

to execute 1,000 innocent people in one moment may point to a psychological need to purge

the world of those things which he hated about his own self.

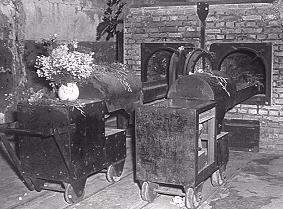

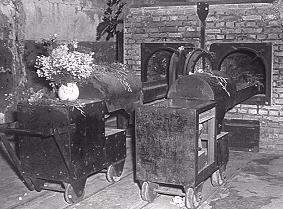

|

|

Ovens in the crematorium of Auschwitz (Associated

Press) |

Whatever it was that inspired Mengele to commit this first act of murder, it continued

to fuel his ambition to be Auschwitz’s premier authority over matters of life and

death. Nowhere was this more apparent than during the selection process, which was

primarily held after trains carrying Jewish deportees had arrived at the camp. According

to Dr. Ella Lingens, an Austrian doctor who was imprisoned at Auschwitz for attempting to

hide some Jewish friends, Mengele relished his role as selector:

Some like Werner Rhode who hated his work, and Hans Konig who was deeply disgusted by

the job, had to get drunk before they appeared on the ramp. Only two doctors performed the

selections without any stimulants of any kind: Dr. Josef Mengele and Dr. Fritz Klein. Dr.

Mengele was particularly cold and cynical. He (Mengele) once told me that there are only

two gifted people in the world, Germans and Jews, and it’s a question of who will be

superior. So he decided that they had to be destroyed.

Mengele performed this task with relish, appearing at selections to which he had not

been officially assigned, always dressed in his best dress uniform. He carried himself

with grace and ease in his shiny black boots, his neatly pressed trousers and jacket, and

his white cotton gloves, while a sea of misery washed up at his feet in the form of

exhausted and starving prisoners. Dr. Olga Lengyel, another inmate-doctor, bitterly

recalls Mengele’s demeanor on the ramp:

How we despised his detached, haughty air, his continual whistling, his frigid cruelty.

Day after day he was at his post, watching the pitiful crowd of men and women and children

go struggling past, all in the last stages of exhaustion from the inhuman journey in the

cattle trucks. He would point with his cane at each person and direct them with one word:

"right" or "left." He seemed to enjoy his grisly task.

This "frigid cruelty" Dr. Lengyels spoke of would oftentimes give way to a

searing hot rage which Mengele would unleash without warning upon those who sought to

challenge the order he sought to establish in the camp. Inmate-doctor Gisella Perl recalls

an incident when Mengele caught a woman in her sixth attempt to escape from a truck

transporting victims to the gas chamber:

He grabbed her by the neck and proceeded to beat her head to a bloody pulp. He hit her,

slapped her, boxed her, always her head -- screaming at the top of his voice, "You

want to escape, don’t you. You can’t escape now. You are going to burn like the

others, you are going to croak, you dirty Jew." As I watched, I saw her two

beautiful, intelligent eyes disappear under a layer of blood. And in a few seconds, her

straight, pointed nose was a flat, broken, bleeding mass. Half an hour later,

Dr. Mengele returned to the hospital. He took a piece of perfumed soap out of his bag and,

whistling gaily with a smile of deep satisfaction on his face, he began to wash his hands.

Despite his demonstrated ability to be both frigid and detached as well as cruel and

brutal, Mengele also demonstrated a carefree, charming side which he used to disarm both

colleagues and victims alike. He acted in a caring, concerned manner when confronted with

exhausted women and their children on the ramp, only to send them to the gas chambers a

moment later. His movie star looks and his confident, authoritative manner made him

sexually desirable to the very women that he degraded, tortured and murdered. The totally

unpredictable nature of Mengele’s personality became his most powerful tool for

exerting control over both prisoners and prison personnel, for it instilled a deep-seated

primal fear into all those with whom he came into contact.

In addition to the selections and beatings, Mengele occupied his time with other

numerous acts of the most base cruelty, including the dissection of live infants; the

castration of boys and men without the use of an anesthetic; and the administering of

high-voltage electric shocks to women inmates under the auspices of testing their

endurance. On one occasion Mengele even sterilized a group of Polish nuns with an X-ray

machine, leaving the celibate women horribly burned. In 1981, the West German

Prosecutor’s Office drew up 78 different indictments against Mengele, charging him

with the most heinous and bestial crimes against humanity, including:

Having actively and decisively taken part in selections in the prisoners’ sick

blocks, of such prisoners who through hunger, deprivations, exhaustion, sickness, disease,

abuse or other reasons were unfit for work in the camp and whose speedy recovery was not

envisaged… Those selected were killed either through injections or firing squads or

by painful suffocation to death through prussic acid in the gas chambers in order to make

room in the camp for the "fit" prisoners, selected by him or other SS

doctors… The injections that killed were made with phenol, petrol,

Evipal,

chloroform, or air into the circulation, especially into the heart chamber, either with

his own hands or he ordered the SS sanitary worker to do it while he watched.

Mengele even introduced sexual degradation to the already dehumanizing process of

selection. Inmates from the various women’s barracks were paraded before him,

stripped totally nude. He often would make each woman stop and answer the basest questions

regarding the intimate details of their sexual lives. While he constantly referred to

Jewish woman as "dirty whores," it is impossible to escape the conclusion that

Mengele’s cruelty was at least in part rooted to a secret sexual longing for these

women whom the Reich had deemed as verboten, forbidden.

Mengele provided endless examples of his devotion to the Nazi order, and the cruel and

murderous lengths he was prepared to reach in order to preserve it. On one occasion a camp

Kapo, Jewish inmates who assisted the Nazi’s in driving inmates to the gas

chambers, attempted to retrieve some inmates from the gas chamber line and place them in

the labor line. Mengele was so furious that he murdered the Kapo with his own pistol. On

another occasion, when the crematoria became too full to accommodate the thousands of Jews

streaming into the camp, he had trenches dug, which were then filled with gasoline and set

ablaze. Both the dead and the living, adults as well as children and infants, were thrown

bodily into these pits to be destroyed under Mengele’s supervision.

While it is nearly impossible to distinguish among Mengele’s murderous acts as to

which ones were worse than others, perhaps one incident exemplifies the demonic nature of

the man perhaps better than most. A Russian inmate named Annani Silovich Pet’ko

witnessed a scene that defies description and comprehension:

After a while a large group of SS officers arrived on motorcycles, Mengele among them.

They drove into the yard and got off their motorcycles. Upon arriving they circled the

flames; it (sic) burned horizontally. We watched to see what would follow. After a while

trucks arrived, dump trucks, with children inside. There were about ten of these trucks.

After they had entered the yard an officer gave an order and the trucks backed up to the

fire and they started throwing those children right into the fire, into the pit. The

children started to scream; some of them managed to crawl out of the burning pit. An

officer walked around it with sticks and pushed back those who managed to get out. Hoess

(the Auschwitz commandant) and Mengele were present and were giving orders.

The body of evidence against Mengele is staggering in both its enormity and variety in

the acts of physical and emotional cruelty that he visited upon thousands of helpless

victims. His behavior practically escapes description, while his motives are virtually

beyond analysis. This is especially true in light of the fact that, for a man who so

relished his role as SS doctor and researcher, who adhered so harshly to the Nazi concept

of order and discipline, he consistently displayed not pleasure but detachment from the

torment and suffering he both caused and witnessed. One psychoanalyst, Dr. Tobias

Brocher,

has postulated that "He (Mengele) didn’t take pleasure in inflicting pain, but

in the power (emphasis added) he exerted by being the man who had to decide

between life and death within the ideology of a concentration camp doctor." While

Mengele practiced this ideology within the context of selector, he also practiced it with

equal fervor in the guise of researcher, the role for which he ostensibly been sent to

Auschwitz by his mentor, Professor von Verschuer.

Contents

Mengele's Research

Prior to his association with Mengele, Professor von Verschuer

had concentrated his research on the subject of twins. His work

had been limited to observing the behavior of twin subjects; he

was prohibited from experimenting on living subjects by the

ethical norms which had prevailed prior to the Nazi era. The Nazis

swept away such norms and in Auschwitz, von Verschuer saw

unlimited possibilities for his protégé, Josef Mengele, to conduct

the types of in vivo experiments he had longed to conduct for so

long. Mengele, ever anxious to please his mentor, arrived at

Auschwitz with a mission to plumb the depths of the human mystery,

and to extract the secrets of human genetics from the living twin

specimens at his disposal.

Mengele ordered the SS guards who assisted him in the selection

process to scour the lines of prisoners for twins. "Zwillinge,

zwillinge," "Twins, twins," the guards would bark harshly as

they marched up and down the ramp as trains transporting new

prisoners arrived. Surviving twins, such as Eva Mozes of Hungary,

remember the moment when they were removed from the line of the

condemned and delivered to Dr. Mengele:

|

| Eva and Miriam Mozes |

When the doors to our cattle car opened, I heard SS soldiers

yelling, "Schnell! Schnell!" ("Faster! Faster!"), and ordering

everybody out. My mother grabbed Miriam and me by the hand. She

was always trying to protect us because we were the youngest.

Everything was moving very fast, and as I looked around, I noticed

my father and my two older sisters were gone. As I clutched my

mother’s hand, an SS man hurried by shouting, "Twins! Twins!" He

stopped to look at us. Miriam and I looked very much alike. "Are

they twins?" he asked my mother. "Is that good?" she replied. He

nodded yes. "They are twins," she said.

While the twins were spared from outright execution, they were

delivered to a decidedly crueler fate. Mengele reserved a special

barracks for his twin subjects, as well as for dwarfs, cripples

and other "exotic specimens." The barracks was nicknamed the Zoo,

Mengele’s holding pen. The twins were his favorite subjects, and

they were afforded special treatment, such as being able to keep

their own hair and clothing, and receiving extra food rations. The

guards were under strict orders not to abuse the children, and

were to look after their well being lest one should fall ill and

die. Mengele became explosively irate if one of his beloved

specimens should happen to die. These twins were referred to as

"Mengele’s Children." It was here in the Zoo that the twins were

to learn of their parents’ true fate in the gas chambers, where

Mengele simultaneously became to them a figure of death and of

life, the man who had condemned their parents and family members

to annihilation, while at the same time sparing their own

lives.

|

|

Ruins of the Infirmary at Auschwitz (Corbis) |

Mengele’s children were also spared from beatings, forced labor

and random selections in order to maintain their good health.

However, Mengele was not motivated by humanitarian urges, but by

his desire to keep his specimens healthy for experimentation.

Ironically, it was his very experiments that extracted the

heaviest physical toll on the children upon whom he lavished such

care and affection, and hundreds ended up dying as a result of his

gruesome deeds. As with other inmates at Auschwitz, Mengele’s

imagination knew no bounds when it came to devising physical

torments for his victims. Preliminary examinations of the twins

were routine enough. The children filled out a questionnaire, were

weighed and measured. However, a more gruesome fate awaited them

at Mengele’s hands. He took daily blood samples from his children,

and sent these to Professor von Verschuer in Berlin. He injected

blood samples from one twin into another twin of a different blood

type and recorded the reaction. This was invariably a searingly

painful headache and high fever that lasted for several days. In

order to determine if eye color could be genetically altered,

Mengele had dye injected into the eyes of several twin subjects.

This always resulted in painful infections, and sometimes even

blindness. If such twins died, Mengele would harvest their eyes

and pin them to the wall of his office, much like a biologist pins

insect samples to styrofoam. Young children were placed in

isolation cages, and subjected to a variety of stimuli to see how

they would react. Several twins were castrated or sterilized. Many

twins had limbs and organs removed in macabre surgical procedures

that Mengele performed without using an anesthetic. Other twins

were injected with infectious agents to see how long it would take

for them to succumb to various diseases.

It is clear that, despite the stated purpose for which he was

sent to Auschwitz, Mengele’s experimentation had absolutely

nothing to do with true scientific research, and was instead the

result of one man’s ambitious and zealous adherence to the Nazi

vision of Aryan supremacy. As surviving Mengele subject Alex Dekel

states:

I have never accepted the fact that Mengele himself believed

he was doing serious work -- not from the slipshod way he went

about it. He was only exercising his power. Mengele ran a

butcher shop -- major surgeries were performed without

anesthesia. Once, I witnessed a stomach operation -- Mengele was

removing pieces from the stomach, but without any anesthetic.

Another time, it was a heart that was removed, again, without

anesthesia. It was horrifying. Mengele was a doctor who became

mad because of the power he was given. Nobody ever questioned

him -- why did this one die? Why did that one perish? The

patients did not count. He professed to do what he did in the

name of science, but it was a madness on his

part.

Madness, indeed, on the part of a man who showered love and

attention on the very children he would sooner or later subject to

his cruel experiments, whom he would more likely than not murder

in pursuit of genetic information that did not exist except in the

imagination of an indoctrinated Nazi ideologue. Madness on the

part of a man whom more than one surviving twin would remember as

a gentle man who loved children! Whence does such madness spring,

how is it possible for two separate and diametrically-opposed

personages manifest themselves within the same individual?

Contents

At

Harmony With Evil

In the words of several Auschwitz eyewitnesses and survivors,

and of historians and psychologists, Dr. Josef Mengele was not

merely of Auschwitz. Dr. Josef Mengele was Auschwitz. Through his

actions and demeanor, Mengele was able to embody the unearthly

contradictions of a death camp where arriving prisoners were

serenaded with waltz music played by a prisoner orchestra, while a

few yards away hundreds of people were reduced to ash in the

crematoria; a camp where affection and comfort were lavished upon

the children living in the Zoo, only so as to keep them healthy

enough for twisted and pointless experimentation; a camp where

Mengele himself escorted his beloved "children" to the gas

chambers, referring to their walks as a game he called "on the way

to the chimney."

|

|

The Buildings of Auschwitz (Associated

Press) |

It is never an easy task to imagine that any human being is

capable of committing acts of such wanton brutality and base

cruelty, acts that bespeak not merely the individual’s disregard

for the value of human life, but his endless desire to degrade and

destroy it. The Holocaust has presented history with an enigma,

with events and personalities that perhaps defy explanation and

meaning. Yet it is in our efforts to prevent such future tragedies

from occurring that we strive to understand what it is that

motivates such individuals to behave in this way.

Josef Mengele harbored a deep-seated ambition to achieve

greatness, and was internally driven from an early age to

distinguish himself as an adult. This is evident in the choices he

made throughout his career as a Nazi. He did not merely join the

army, he joined the SS; and he did not merely join the SS, he

joined the Waffen SS; and when posted at Auschwitz he did not

perform some selections, he seemed to be present at almost

all selections. In every way possible, Mengele sought to

advance his own interests by demonstrating that there was no one

else in the field who did things quite like he did, that there was

no one else with his sense of devotion or zeal.

But does this go far enough towards explaining the leap from

ambitious young scientist to murderous barbarian? Does this

explain the transformation of an affable young man named Beppo to

a cold-blooded, torturous demon? Author and professor Robert Jay

Lifton has posited that for one such as Mengele, such a duality

was possible because of a phenomena he refers to as

"doubling":

The key to understanding how Nazi doctors came to do the work

of Auschwitz is the psychological principle I call "doubling":

the division of the self into two functioning wholes, so that a

part-self acts as an entire self. An Auschwitz doctor could,

through doubling, not only kill and contribute to the killing,

but also organize silently, on behalf of that evil project, an

entire self-structure encompassing virtually all aspects of his

behavior. The individual Nazi doctor needed his Auschwitz self

to function psychologically in an environment so antithetical to

his previous ethical standards. At the same time, he needed his

prior self in order to continue to see himself as humane

physician, husband, and father. The Auschwitz self had to be

both autonomous and connected to the prior self that gave rise

to it.

While there is a certain logic to Lifton’s argument, that

doctors accustomed to adhering to the Hippocratic oath needed an

"Auschwitz self" to function in the death camp, he himself points

to Mengele’s especial affinity for work in this milieu. In other

words, it was not a great leap that Mengele was required to make

in order for the Auschwitz self to emerge from the prior self:

|

Josef Mengele in 1956

(Associated Press) |

Mengele’s embrace of the Auschwitz self gave the impression

of a quick, adaptive affinity…Doubling was indeed required of a

man who befriended children and then drove some of them

personally to the gas chamber. Whatever his affinity for

Auschwitz, a man who could be pictured under ordinary conditions

as "a slightly sadistic German professor" had to form a new self

to become an energetic killer. The point about Mengele’s

doubling is that his prior self could be readily absorbed into

the Auschwitz self; and his continuing allegiance to the Nazi

ideology and project enabled his Auschwitz self, more than in

the case of other Nazi doctors, to remain active over the years

after the Second World War.

Perhaps that is the greatest mystery, not that the process of

doubling occurred within Mengele, but the fact that it occurred

without conscious effort on his part, the fact that the Auschwitz

self seemed to rise from within, rather than split off from, his

prior self. Why did Mengele slip into the role of the Auschwitz

self with such ease? What was it about his psychological makeup

that allowed him to convey the appearance of his prior self while

simultaneously behaving as the Auschwitz self? Because Mengele

himself died before he could be captured and interviewed, it is

possible that the last word may be that, at least in his case,

such behavior was possible because he was simply an embodiment of

evil, and there is no psychological way of explaining how he

became so.

Contents

Epilogue

Dr. Josef Mengele fled from Auschwitz on January 17, 1945, as

the Soviet army advanced across the crumbling German Reich towards

Berlin. During the first few years of the post-war era, Mengele

remained in hiding on farm near his native Gunzburg. He assumed a

fake identity, and worked as a farm hand, keeping informed of

events through secret contacts with old Gunzburg friends.

Incredibly, he at first aspired to continue his career as a

research scientist, but it became increasingly apparent that the

Allies were not going to let a notorious war criminal such as he

simply resume the life he had enjoyed prior to the war without

paying for the crimes he had committed during it. Mengele finally

decided that he was no longer safe in Europe and escaped through

Italy to an ocean liner bound for Argentina.

|

|

Mengele in Paraguay, 1960 (Corbis) |

Mengele arrived in Argentina in 1949, a country that was ruled

by the popular dictator Juan Peron. The right-wing ruler had

already cultivated a friendly relationship with Nazis in Europe,

as well as with those who lived in the German expatriate community

in Argentina. Mengele was able to slip unnoticed into such a

setting with ease and had soon established a network of Nazi

devotees who were willing to help him assume a new identity in

South America.

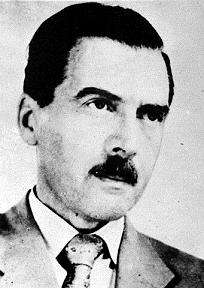

|

Photo for Mengele's false ID card

(Associated

Press) |

Mengele was to spend the next thirty years on the run from

international authorities. While he received aid and shelter from

the neo-Nazi network in Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil, Mengele

was also inadvertently assisted by a lack of commitment on the

part of the West German government to bring the Angel of Death to

justice, and a similar lack of commitment on the part of the

United States Justice Department. The Israeli government had no

such lack of commitment to his capture, trial and execution. In

fact, Israeli agents were close to seizing Mengele on a handful of

occasions in the early-to-mid 1960s. However, international uproar

over Israel’s kidnapping of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann from

Argentina in 1960, and pressing security issues involving hostile

Arab states, sidetracked Israeli efforts to pursue Mengele.

While Nazi-hunters such as Simon Wiesenthal continued to press

for Mengele’s capture and execution, the notorious Nazi doctor

seemed to drop off the radar screen of most international

governments. Interest in his case was suddenly reinvigorated when,

on January 17, 1985, a group of Auschwitz survivors returned to

the death camp to memorialize friends and family who had perished

there. A week later, many of the same survivors gathered in

Jerusalem to try Mengele in absentia. The event was televised

around the globe, and for four consecutive nights, the airwaves

were filled with images of survivors recounting their gruesome,

barbaric treatment at the hands of Josef Mengele. Within less than

a month, both the United States Justice Department and the Israeli

government had announced that the case of Josef Mengele was

officially reopened and strategies were redrawn to bring the Nazi

doctor to justice.

|

Josef Mengele, Nazi war criminal

(Associated Press) |

However, these fledgling efforts were stopped in their tracks

when, on May 31, 1985, West German police raided the home of Hans

Sedlmeier, a lifelong friend of Mengele’s, and his contact person

in Europe. The police seized several letters from Mengele and

other German expatriates living with him in Brazil, and Brazilian

authorities were immediately notified. Within a week Brazilian

police had identified the families that had harbored Mengele, and

through them were able to locate the grave where Mengele’s body

had been buried after a drowning accident in 1979. Forensic tests

on the skeletal remains confirmed that the body was indeed that of

Josef Mengele. Survivors of Mengele’s treatment who had longed all

of their post-war lives to confront this cruel and demonic man

denied that this could indeed be him. Many still live for the day

when they will be able to extract justice for their suffering from

the man who was responsible for so much of it, both during and

after the war. Alas, Mengele has escaped earthly judgment through

that act over which he sought to wield total control -- death

itself.

Contents

Bibliography

Astor, Gerald. The Last Nazi: The Life and Times of Dr. Joseph Mengele. Donald I. Fine, Inc.: New York, 1985.

Lagnado, Lucette Matalon and Sheila Cohn Dekel. Children of the Flames: Dr. Josef Mengele & the Untold Story of the

Twins of Auschwitz.

Lifton, Robert Jay. The Nazi Doctors. Basic Books: New York, 1986.

Posner, Gerald L. and John Ware. Mengele: The Complete Story. McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, 1986.

For Further Reference:

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

Kor, Eva Mozes. Echoes from Auschwitz. C.A.N.D.L.E.S. Publications: Terre Haute, IN, 1995.

Nyiszli, Dr. Miklos. Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Story of Survival. Fawcett Crest: New York, 1960.

Wiesel, Elie. Night. Bantam Books: New York, 1982.

|

About the Author

Douglas Lynott

Doug Lynott holds a BA in English from St. Norbert

College in De Pere, WI, as well as a Masters in Public

Administration and Urban Affairs from Michigan State University. A

native of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, he currently lives in the

metropolitan Washington, D.C. area and works for the federal

government. His interests include running, writing, Irish folk

music and cooking. |