Dianne Huntress for The New York Times

OTHER HEIGHTS Jon Krakauer has a new book.

BOULDER, Colo.

FRESH from writing one of the most popular books ever published about mountain climbing, Jon Krakauer circulated a proposal for his next project. An account of the 1984 killings of a Utah woman and her infant daughter, the new book promised outlaw sex, bizarre rituals, unknown history, an examination of the tragic consequences of faith all built around murder in the service of a home-grown religion.

Editors were perplexed.

" `Where are the mountains?' " asked one editor, Mr. Krakauer recalled. "People think of me as this outdoor writer. But I'm really a seeker, a doubter. I'm interested in those people who take things too far, because I see something of myself in them."

There is a moment in all his books when Mr. Krakauer turns the story on himself and presents an imperfect human an author as guilty of the hubris, doubt and foolishness that push his nonfiction characters to extremes. So it is in his latest book, "Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith," which Doubleday is bringing out this week, complete with a publicity agent's dream controversy loud condemnation of the book by his primary target, the Mormon Church.

Lynn Johnson, right; Douglas C. Pizac, left.

Dan and Ron Lafferty, from left, brothers who claim God told them to kill their sister-in-law and 15-month-old niece. |

Dianne Huntress for The New York Times

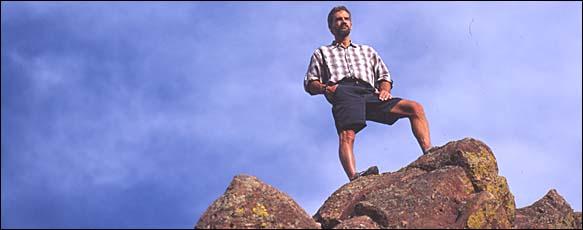

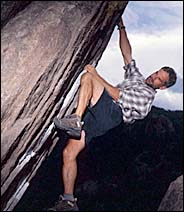

FIGHTING TRIM Jon Krakauer still climbs, scaling rock walls in Colorado, where he lives. |

FOUNDER Joseph Smith of the Mormon Church. |

"I don't know if God even exists, although I confess I find myself praying in times of great fear, or despair, or astonishment at a display of unexpected beauty," he writes. "In the absence of conviction, I've come to terms with the fact that uncertainty is an inescapable corollary of life."

Until six years ago, when Mr. Krakauer wrote

In a story of arrogance and missteps at the highest altitude, Mr. Krakauer and his party reached the summit of the world's highest mountain in the spring of 1996. On the descent, four of his teammates died, and Mr. Krakauer blamed himself, in part.

The book was a sensation, riding best-seller lists for two years, translated into 24 languages, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Critics Circle award. There are now more than 3.6 million copies in print. It made Mr. Krakauer, a former carpenter and fisherman who scrapped for a living as a freelance writer, a rich man. He was free to pursue his passions and settle down along the Front Range here in well-manicured Boulder. The book followed "Into the Wild," Mr. Krakauer's story about a lost American soul, Chris McCandless, who died looking for inner meaning without sufficient outer protection in the Alaskan bush. It also became a best seller.

Now, with "Under the Banner of Heaven," Mr. Krakauer has begun his own culture war. If he thought the mini-industry spawned by his Everest book competing books, death threats and continuing Web battles was a nuisance, he may one day look back on that experience as a minor dust-up compared with what could follow his book questioning religion.

Already, the Mormon Church has questioned his motives and veracity, while pointing to some secular publications like the Economist magazine that have criticized him for failing to explain why people are drawn to the church.

The gist of the complaints is that, having climbed to the top of the world and written well about it, does an admitted agnostic really think he can take on a popular religion? Or even get it?

Mr. Krakauer, whose friends both praise and fault him for his laserlike intensity, certainly takes his swings.

A year ago, the nation was appalled at the kidnapping of Elizabeth Smart, the sunny-faced Utah girl of 14 whose abductor says he was following early Mormon scripture in taking her as one of his brides. But as Mr. Krakauer writes, Joseph Smith, the Mormon Church's founder, also took a 14-year-old girl as one of an estimated 40 wives, explaining to her that God had commanded her to become part of his harem.

"My friends in Utah say Elizabeth Smart was more vulnerable to this kind of thing because the culture puts so much emphasis on obeying the word of God," Mr. Krakauer said.

In the book, Mr. Krakauer examines Mormon fundamentalists, the tens of thousands of true believers living mostly in Utah who broke away from the original Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The splinter groups are the American Taliban, Mr. Krakauer says, living in desert theocracies where pubescent girls are forced into marriages with old graybeards who rule with an iron fist. These polygamous communities are against the law, but usually tolerated by officials who see a little bit of great-grandpa's pioneering ways in the modern sects.

The biggest of these communities, Hildale/Colorado City, on the Utah-Arizona border, is full of houses the size of a Days Inn motel, stuffed with dozens of wives married to self-styled Mormon fundamentalist patriarchs. The community is in open violation of the law, Mr. Krakauer and others have noted, but faces little legal sanction and also manages to have one of the highest ratios of welfare recipients in the country.

His main focus is on Dan and Ron Lafferty, a pair of Utah brothers who believed they were ordered by God to kill their sister-in-law and her 15-month-old daughter. Brenda Lafferty had her throat slit with a 10-inch boning knife, and her daughter, Erica, was also stabbed. Dan Lafferty is serving a life sentence and his older brother, Ron, is on death row. The brothers said they did it because Brenda opposed their plan to take multiple wives.

Mr. Krakauer draws a connection between the revelations the Lafferty brothers claimed guided them and early Mormon acts of "blood atonement," in which followers targeted victims because of purported divine inspiration. Ron Lafferty, Mr. Krakauer notes, was a Republican city councilman and devout Mormon, who came to believe that his religion had lost touch with its roots, which allowed men to practice polygamy and to receive divine revelation.

Mr. Krakauer faults the modern Mormon Church, perhaps the fastest growing religion in America, with worldwide membership approaching 12 million, for failing to honestly address a past where taking young wives, killing on behalf of God and open disdain for the Constitution are papered over in place of a more Osmond-friendly image. Often overlooked by mainstream historians, the story of how a church founded by radicals who practiced an early form of communism and sanctioned sexual promiscuity through multiple wives has come to be known for white-bread conservatism is a compelling American tale.

The church officially renounced polygamy in 1890, and excommunicates members who openly practice it. But officials in Utah say up to 60,000 people continue to live in polygamous families there.

The church issued a five-page, single-spaced rebuttal of the book two weeks before publication. They found some relatively minor factual errors in the book, which Mr. Krakauer has promised to correct, and they took issue with one of his central points.

The book "is a full frontal assault on the veracity of the modern church," Mike Otterson, a church spokesman in Salt Lake City, said in a statement. "His basic thesis appears to be that people who are religious are irrational, and that irrational people do strange things."

In tying the crimes of the Lafferty brothers to the roots of the church, Mr. Krakauer has smeared an entire religion, Mr. Otterson said in the statement. "Krakauer unwittingly puts himself in the same camp as those who believe every German is a Nazi, every Japanese a fanatic, and every Arab a terrorist."

Doubleday, which is bringing out a 350,000-copy first printing of the book, seems delighted with the controversy. Its publicists promptly faxed the Mormon Church rebuttal to reviewers, and passed on phone numbers of church spokesmen.

Church officials say they agonized over responding in such a splashy way to the book, but decided that they had to make their stand, even at the risk of running the book up the best-seller charts.

Mr. Krakauer, a wiry, bearded, 49-year-old man with a sense of humor that is rarely evident on the pages of his books, admires the Mormons for their faith, he said during an afternoon in Boulder.

"I grew up with Mormons," said Mr. Krakauer, who was raised in Corvallis, Ore. "I like this culture. What I'm less comfortable with is the mind-boggling certainty of this or any religion."

He seems unfazed by fame; he has been married to the same woman, Linda Moore, for 23 years, and moves around Boulder with minimal interruptions from strangers. He can seem tightly wound, but the guilt and soul-searching that followed Everest are genuine, say friends.

"The controversy over Everest changed him," said John Rasmus, the editor of National Geographic Adventure Magazine, who has worked with Mr. Krakauer for 20 years at other publications. "Jon felt the Everest book was somewhat the result of being in the right place at the right time and that he had profited from what turned out to be a tragedy."

In a postscript in a later edition of the book, Mr. Krakauer called himself "stubborn and proud and loathe to back down from a fight," and wished that he had been "a little less strident" in his post-Everest debate with a climbing guide, Anatoli Bourkreev, who died shortly after his own book on the deadly season came out. Mr. Krakauer had faulted the guide for leaving the summit before all of his clients were down the mountain, and for not using supplemental oxygen.

With the new book, Mr. Krakauer has fresh demons on his flanks. In their rebuttal of Mr. Krakauer, Mormon officials describe him as "agnostic," a label Mr. Krakauer does not dispute.

"I'm trying to figure out religion," he said. "I'm not a social reformer, but I am troubled by this sheeplike acceptance that faith is always good."

Mr. Krakauer's father was a Jew from Brooklyn, an agnostic and a medical doctor, who moved to Oregon and became friends with another famous outsider, the writer Bernard Malamud. In "Into the Wild," Mr. Krakauer wrote some less-than-flattering things about his father, now dead. They reconciled before his death, he said.

The latest book started as an inquiry into the nature of faith. He chose the Mormons because he has always been fascinated by them, he said, and because they have long tried to convert him, with missionaries showing up on his doorstep.

His research led him to Dan Lafferty, who cooperated with Mr. Krakauer from his cell in Utah, and still shows no remorse for his crimes. The church says Mr. Lafferty is simply a murderer who used his own cryptic religious revelations as an excuse to go after his sister-in-law because she opposed his views on polygamy.

"I don't believe Dan Lafferty is crazy or a psychopath," Mr. Krakauer said. "He is an example of an inevitable outcome of strong belief. The modern church's refusal to acknowledge its history has spawned people like Dan Lafferty."

This kind of deduction is far too simple, say Mr. Krakauer's critics. If in fact the early church history is so toxic that it continues to inspire people to murder, why are there not more people like the Lafferty brothers? The murders, the church says, are anomalies not evidence of cause and effect.

MR. KRAKAUER still climbs, often twice a week with a friend, scaling the rock walls in Boulder's backyard. He does not consider reaching the summit of Everest a major mountaineering achievement.

"I'm kind of freaked out by it all now," he said. "If I had to write a climbing résumé now, I wouldn't even put Everest on it."

Mountaineering is like a religious faith in one way, he said, because it defies reason. And climbing Everest is the ultimate irrational act.

"The plain truth is that I knew better but went to Everest anyway," Mr. Krakauer wrote at the start of "Into Thin Air" in 1996. "And in doing so I was party to the death of good people, which is something that is apt to remain on my conscience for a very long time."

He wrote the Everest book as a cautionary tale, blaming commercial guides for rushing overeager clients up a mountain that requires expertise and patience and can't always be bought. It has had the opposite effect, of drawing more people to the mountain, Mr. Krakauer said, and now he is disgusted with the climbing world's continued focus on Everest. "The owner of an Everest guiding service recently thanked me for bringing him more clients," Mr. Krakauer said, shaking his head.

If the new book has the same effect on the Mormon Church, they may be thanking him in Temple Square, the church headquarters, as well.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company