|

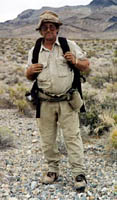

Desert diary: Jerry Freeman chronicles his

|

||

Main Story Diary entries

Archives 'New Lost 49ers' complete successful trek across West Modern 49ers struggle over historic Nevada trail

Route map Archive photos |

Saturday morning, April 26, 1997 At first light, I climbed down off my "telecommunications perch" and recovered my gear. Then proceeded to penetrate deeper and higher into "Dreamland," generally following the ridges that paralleled Nye Canyon. I never dropped into it en route, fearing detection, but my obsessive pursuit of high ground consumed precious time and energy. But WOW! At 10:30 in the morning, I lay beneath downed cactus trees on a windswept ridge overlooking the most restricted place on Earth: Papoose Lake, the very soul of "Dreamland." The aliens appeared to be in short supply. So were the ex-Navy Seals, who were supposed to be protecting this place. North of my position, I occasionally caught sight of the Black Hawk helicopter, chasing the tourists away from the Air Force's front door near Groom Lake. That night as I lay awake in the darkness, high above that ancient playa, I half expected a "close encounter of the third kind," but no such luck. Hale-Bopp gleamed in the northwest, the comet's remarkable brilliance strengthened by the clear desert air. Near the mountainous side of Papoose I saw lights. Security vehicles? Hangar doors opening and closing? I don't profess to know. My purpose for intruding here was not to document UFO sightings. Nor was I here to compromise national security. Still, some of my closest friends voiced serious reservations about this expedition. One characterized my intrusion as "evil" and hinted darkly of grave consequences for my heavenly salvation should I not alter the coordinates on my moral compass. Bruce Larrick, who check-pointed the unrestricted portions of the '49er expedition, pulled me aside one day and told me: "Hey, pal, what part of NO don't you understand?" My wife believed, in the event of my arrest, the '49er team's credibility would be lessened and our previous accomplishments jeopardized. She also felt I was selfishly undertaking a risk that could, conceivably, have fatal consequences. Guards here carry automatic weapons. Well, I must admit, my reasoning is probably a bit muddled, but my conscience remains clear. Secretary of Defense William Cohen, in a commencement address to the Air Force Academy's graduating class of 1997, proclaimed: "We must learn from the past by extending the `lamplight' of history." My only purpose for being in this forbidden land is to pay homage to our past. To hold aloft that "lamplight" for those brave men and women who forged this great nation's heritage. How ironic that, 150 years after they passed, I'm desperately dodging my own country's militia, just to see the places where they labored so valiantly. These were not military people. These were not mountain men. They were just people, like you and me, dreaming of a better life for their husbands, wives and babies. That innocuous lake bed below me was of pivotal importance to their survival. After journeying nearly 2,000 miles since leaving the verdant corn fields of the midwest, 100 men, women and children gathered together here for the last time. Following contentious debate, their remarkable cohesion shattered, never to be mended. On the morning of Dec. 2, 1849, nearly half the wagon train, led by the Jayhawkers and Briers, broke away to the west in a desperate attempt to escape the wilderness. Topography would soon force them south into the deepest driest valley in the western hemisphere, a land the Indians fearfully called "Tomesha," land of ground afire. A geographical wonder, now known throughout the world as Death Valley, and whose name can be directly attributed to those lost emigrants of long ago. The remaining '49ers stayed four more days beside Papoose Lake's sterile shoreline, while scouting for an escape route. On Dec. 6, they loaded their meager possessions and drove their oxen south toward what is now known as Nye Canyon. One of them carved the date in the canyon wall, marking their passage. In my pocket, I carried a weathered photograph, taken more than 50 years ago, of that inscription. Would I find it? Saturday, April 26, noon A long, last look at Papoose and I began my descent into Nye Canyon to search for the inscription. I was to be crushingly disappointed. There were so many canyon walls, I was just not able to locate it, despite my photograph. If only I had two more quarts of water, to allow me one more day to search. I did find something, which partially soothed my chagrin and could possibly be of equal significance: an oxen shoe. I have never seen one outside the confines of a museum. Only the '49ers, to my knowledge, ever drove a yoke of oxen through this wild and hostile canyon. Climbing out of Nye Canyon, I had a close call with a rattlesnake. Fortunately, I saw it first. Usually, when I encounter a rattler in the back country, we're both eager to avoid each other. This one, however, was not intimidated by my presence in the least. To be bitten here, so deep in the wilds, could prove lethal. I gave him a wide berth. By nightfall, my situation was becoming dangerous. I was completely out of water, with 22 miles between me and Cane Spring. I attempted to call Doyle at 10 to advise him of my predicament; but phone was useless, the batteries dead. I decided to leave all but the essentials, which meant leaving my $200 binoculars as well as my phone, extra canteen, sleeping and cooking gear, extra clothes and provisions. I would travel light and fast as soon as the moon cleared the horizon. Lying in darkness above Papoose Lake, I waited anxiously for the moon to light my way. I can honestly say, without guilt or hesitation, that, for the first time in a long time, I was genuinely afraid. Not of losing my way or injuring myself, but from a latent dread of not reaching water. By 1 a.m., I was homeward bound, aiming for a light far in the distance that marked a Department of Energy structure near Frenchman Flat. Before I had traveled two hours, my mouth had dried shut. No spit, complete cotton mouth. Ten miles further, at dawn, I entered the Department of Energy's Atomic Waste Storage Yard. With the rising sun at my back, I evaded security and located a hose on the side of a building. It was live. I drank deeply, replenished my canteens and slipped beneath a mobile trailer. I drained both containers, crawled back out, refilled and disappeared into the desert.

|